Ari interviews The Telling Room author Michael Paterniti (part one)

Michael Paterniti’s book The Telling Room documents his pursuit of an obscure Spanish cheese – a cheese he first encountered while working at the Zingerman’s Deli back in 1991.

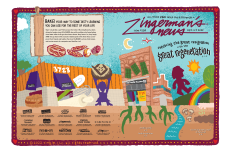

On Thursday, September 26, 6:30pm, Mike will visit the Deli and tell the story himself. He’ll sign copies of the book, as well as copies of the Zingerman’s newsletter that features the book’s release. We’ll also taste a delicious selection of fine Spanish foods, including many of our favorite traditional cheeses. Copies of Michael’s new book are available at fine bookstores everywhere, but seats at the event are limited. Reserve a seat online or call 734-663-3400!

It’s over twenty years ago now that you were here. What brought you to Ann Arbor?

I came to write fiction in the MFA program, under the great Nick Delbanco and Charlie Baxter, both amazing writers and Ann Arbor legends in their own right!

What do you remember about the town?

I remember Ann Arbor as a place in which you could find anything—anything in the world (great books and movies, great food and minds at work)—within a one-mile radius of campus. I also loved that open Midwestern friendliness. Coming from the East, I didn’t know what to do with it at first. Like, did that guy really just say hi to me for no reason?

The book begins really with your work here at Zingerman’s, or at least, behind the scenes on our newsletter. What do you remember about the Deli from those days?

The Deli, for me, was a little slice of heaven, a foodie paradise, a spectacular world unto its own. I was interested in food, but didn’t have the money to be really interested in it. That is, I was broke, and I really wanted to try that Finnish licorice, but I knew the Finnish licorice would be like my gateway drug, and next I’d be imbibing the sherry vinegars and scarfing latkes, throwing down sandwiches (that sandwich board was like standing before the departing flights screen in a foreign airport) and demanding Italian chocolates while being fanned by my pet monkey, Bubbles. It was a little decadent in the deli, and I loved the hum and energy of it, just being swept up in it.

Can you tell people who Ambrosio is and a bit about Páramo de Guzmán cheese?

So Ambrosio Molinos is a farmer

in the little Castilian village of

Guzmán (pop. 80), in north-central Spain. He also happens to be

a force of nature, a larger-than-

life character of Falstaffian

belly, and really perhaps the best

storyteller I’ve met in my travels as

a journalist. The cheese he made came

from a centuries-old, discontinued family recipe. One day in the Eighties, he bought a bunch of Churra sheep, began grazing them on the highlands around Guzmán, took their milk to a little stable across from the house he was born in, and made cheese, aging it in a family cave nearby. When people in the village were given some, they thought it was amazing, like the old house cheeses they remembered their mother serving, robust and Manchego-like. And so the cheese was passed along, from village to village, and then to Madrid, where it was sold. The legend of the cheese is that the Spanish royal family loved it, as did the British royal family. It was served to Ronald Reagan and Frank Sinatra. Fidel Castro tried to buy all of Ambrosio’s stock. The cheese won several awards, and in 1991, I know you brought it back from London, to sell here at Zingerman’s, which is where I first learned about it, when I was proofreading your newsletter!

So you carried that little clip from the newsletter in your wallet for nearly ten years?

I mean initially it was in my wallet. Eventually it went in a file. And then when I went to Spain on assignment in 2000, to spend time with the great futurist chef Ferran Adria, it went back in my wallet. Those four paragraphs you wrote in 1991 felt like the beginning of a fairytale: Once upon a time there was a piece of cheese, and a cheesemaker named Ambrosio… I remember, too, that it was the most expensive cheese Zingerman’s had ever sold at the time.

Early in the book you write, “What was so crazy about believing in purity—and then going to find it?” In many ways, that’s the story of our approach to visioning work. What would you say on the subject today, knowing what you know about the cheese and Ambrosio and life?

That this ideal of purity, at some level, is achievable, given that you’re deliberate in how you live your life. I mean there are all sorts of sugary temptations in this world, but what captivated me about Ambrosio was his rejection of the packaged modern world. As he said, “The world is rushing forward, so I need to go back.” But it wasn’t just a sort of unrealistic, antediluvian rejection of that world. I mean, he has a cell phone. He drives a car. He enjoys certain creature comforts. But it’s this idea of having a code or philosophy, and then sticking to it. Long ago, he decided to feed his body with homemade wines and chorizos and cheeses, with lamb raised right there on the land, and he’s tried not to waver from that.

It’s a long way from Ann Arbor to Guzmán—what was it like when you first arrived there?

Oh, the place is beautiful! I thought that straightaway. About a half-mile above sea level, bathed in this thin, ecclesiastical light. There were vineyards and wheat fields, and then Guzmán was there on a hill, above it all, looking down on the Meseta. The village itself was crumbling and dying, too. Some of the houses were split open and you could see a tattered book, someone’s bloomers. Everything—and everyone—seemed so old, as opposed to Ann Arbor, which buzzes on that youthful energy of the university, and those connected to it.

And then on that first visit, Ambrosio told me this incredible story about his cheese, in essence how it had been stolen from him by his best friend, and how he was now plotting the best friend’s murder. He unraveled this story over about eight hours in a place there known as a “telling room.” It was a little room built above the cave, where people went to eat and sit by the fire and tell their stories.

Part Two will appear tomorrow.

Zingerman’s Art for Sale