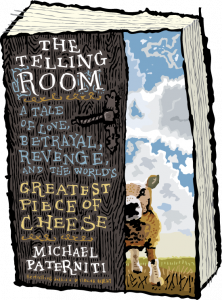

Ari interviews The Telling Room author Michael Paterniti (part two)

Michael Paterniti’s book The Telling Room documents his pursuit of an obscure Spanish cheese – a cheese he first encountered while working at the Zingerman’s Deli back in 1991.

On Thursday, September 26, 6:30pm, Mike will visit the Deli and tell the story himself. He’ll sign copies of the book, as well as copies of the Zingerman’s newsletter that features the book’s release. We’ll also taste a delicious selection of fine Spanish foods, including many of our favorite traditional cheeses. Copies of Michael’s new book are available at fine bookstores everywhere, but seats at the event are limited. Reserve a seat online or call 734-663-3400!

You spent nearly a decade pursuing this cheese and the man who had made it. I’d imagine you caught a bit of grief, or at least disbelief, from people you knew during that time?

All the time. On those occasions when I told people I was writing about cheese, some were quick to say, “Oh, like ‘Who Moved My Cheese?’” And I would respond, “Sorta—but with a Shakespearean murder plot.” I think, in the end, time was a friend to the book. I was waiting to see what would happen between Ambrosio and Julian, the man he claimed had stolen his cheese. To see how that murder plot would really unfold, but I also came to this realization that what I was doing was Slow Reporting, too. And some Slow Living. In my job as a magazine journalist, I never quite had that luxury. You might land in Cambodia or India or the Sudan and have X days to get your story—and then get out. I loved the idea of sinking in a little. Our family lived there for a summer, too, and those are some of my best memories of the kids.

I love all the footnotes in the book. Can you share the story behind them?

Castilian storytelling is a wild business, full of digressions and asides, historical footnotes and factoids. Often, it’s what gets said in the marginalia, or that excursion away from the story itself, that reflects the truth of the story being told. The legend of the great Castilian hero, El Cid, says as much, for instance, about Ambrosio’s blood feud with his best friend, Julian. I’ve sat in Ambrosio’s telling room for an entire days, listening to him tell a story so full of digressions that even by midnight, he still might not be done. So I wanted the book to reflect the spirit not just of Slow Food but Slow Storytelling, the way it’s practiced in Guzmán. Besides that, they were a blast to write!

Early in the book, Ambrosio tells you about eating in an “ancient way”—probably what we at Zingerman’s would call traditional. He says, “You start by eating good beans and a good lettuce salad with olive oil and tender lamb chop or fresh rabbit. Everything is accompanied by a good piece of wheat bread and a good wine and good friends and, at the end, a sip of brandy.” It sounds fabulous. Have you had that meal? Maybe we should recreate it?

I had that meal—and many others like it! Each awesome in their own way. If you re-create it, I’ll be there!

One of the things I’ve learned about writing is to push forward and let the seed of what’s inspiring grow and develop and see where it takes me. You wrote, “The story itself spoke, calling out for a teller and a hero. It craved a dramatic ending, even if the truth needed tweaking or the lead needed revising.” What have you learned about writing from pursuing the cheese and the story? About life?

That everything—a political campaign, marriage, family dinner—is a narrative collaboration, or battle. And that you need great patience in order to deconstruct someone’s story or legend or myth, to find the truth. Or your truth. You need great patience to figure out what it is you mean to say—and what you believe. What I learned about writing is that on certain days you find yourself on a very lonely island, feeling a little betrayed by your own limitations, and the only way off is to keep writing the words that become the bridge that lead eventually to the epiphanies that make it all worthwhile again.

Food plays a pretty different role in the rural Spain in which Ambrosio grew up than in the America that we were raised in. Can you talk a bit about that?

Ambrosio describes the lost art of eating like this: “As a child, I lived an old kind of life. Not like people living in Madrid or Tokyo or New York. It was a way of life that meant you raised chickens from the egg, you had a good relationship with your dog, you held your animals and prepared the animals for your table by giving them your love. It was the end of an era when everything was natural. There were no mad cows, there was no such thing as preservatives here. We ate in an ancient way.” I think the big thing is that the food grown there, and eaten there, is inextricably linked to their identity, to who they are, and their sense of themselves. Ambrosio describes what it was like in 1955, and he’s describing what it’s like for him today, too.

You wrote that making the cheese again “became Ambrosio’s overriding obsession.” Is it fair to say that that obsession passed through to you. Do you think you became a bit obsessed with the idea of telling the story of his obsession?

Exactly! And then after I’d faithfully laid down the legend of his cheese as he told it, I became obsessed with finding the truth behind it, too.

You share the story of Ambrosio and what he said as he would taste each successive batch of cheese in his drive to reproduce the family’s old recipe. “For this, he had a little ritual,” you wrote. “Before taking a bite, he’d ask the cheese, ‘Are you the one who’ll remember us?’” That’s a nice image—the idea of a mutually beneficial, meaningful relation- ship between traditional food and its maker.

I love that. And I love the way Ambrosio really does talk to his animals and to the grapes that make the wine, etc. Everything is animated in his world—and alive. And that forces a deeper kind of respect for everything.

Part three (conclusion) will appear tomorrow.

Zingerman’s Art for Sale