Parm Project: Visiting Caseificio Ravarano #3084, 600 Meters

Have you heard about our Parm Project? Throughout the Zingerman’s Community of Business we’ve embarked on a project to source Parmigiano Reggiano from multiple dairies in Italy’s Parma region and share them with you. We want to spread the word that this cheese is not a singular thing—there are a range of flavors and characteristics in Parmigiano Reggiano varieties, just like with fine wines and olive oils.

Today Grace Singelton, a managing partner at Zingerman’s Delicatessen is sharing highlights from her trip to Caseificio Ravarano #3084

I had the pleasure of spending time at Caseificio Sociale di Ravarano, where much of what I learned about the Parmigiano Reggiano cheese making was reviewed, but in much more detail and depth than I’d heard previously. Damiano is the cheese master at Ravarano and, like all cheese masters, his presence sets the tone for the production and the staff. Maybe it’s due to his study of engineering, but Damiano gave the most thorough and detailed accounts of the entire cheese making process. He gave us information on everything from the forage available in the fields to the care of animals and the gathering and transportation of milk, through the handling of the milk by the cheesemaker and all of the steps involved in creating and aging Parmigiano Reggiano.

I left with a more thorough understanding of the entire process. There are many traditions present in the production of Parmigiano Reggiano, and many newer technological advances have been added as well—older equipment, like using a hawthorn branch to cut the cheese curds, have been replaced with newer present day materials. Now stainless steel cutters have been formed for cutting the curds, but made in the same shape as the tree branch.

Damiano, the Cheesemaker

A 30 cheesemaking veteran, Damiano is a fourth-generation cheese maker who is very highly regarded and successful, but he wasn’t planning on being a cheesemaker. He started working when he was very young, and he had been an active participant in all of the cheesemaking operations throughout his life. He was studying engineering when his father passed away, but he was only 23. He returned to the facility to take over the business and that made him the person in charge at a young age. He says it was difficult, but he studied and is now happy—he gets good results and is considered a good cheesemaker. His mother is still there with him and involved in the business, helping during the production, and watching over the cheesemaking process. You can see her in the photo below, looking over the process next to her son.

Damiano has this to say about cheesemaking:

There are four tools needed to make the cheese: time, temperature, 1,000-year-old technology, and your hands. Physically making the cheese is the only way to learn—you can study, but really you only learn after a mistake is made. Your hands and your mind are the key to your success in cheese making. Man, mountain, cheese, farm are all linked.

Damiano starts his day at 5:00 a.m. He looks at the cream to see how the milk is and he decides how soon he should start. The day we visited he told us “the milk was good, outside is beautiful, and it helps the cream and the milk.” It was a sunny day, cool but not cold, and warming up nicely with the sun.

The Cheesemaking Process:

- The evening milk is brought to the dairy. It must arrive at the dairy within two hours of milking, and this limit means that the milk source cannot be a great distance away from the cheese production, keeping it part of the local economy. During the night the cream naturally rises to the surface and in the morning the milk is surface skimmed, removing a portion of the cream.

- There are 10 small farms supplying this dairy with an average of 30 cows at each farm. None of the farms have enough milk to fill a vat, but each farms milk is always divided up the same way. Damiano knows which farms pair well together, and although it may look like he does the same work for every vat, they were each treated differently.

- The morning milk arrives and is mixed with the skimmed evening milk and moved to the vats where the starter is added to the milk.

- When it is at the correct acidity level the rennet is added. The temperature is raised from 18 to 34 C (64-93 F) and after about 10 minutes it begins to coagulate. From this point on the main goal is to remove the water.

- The curds are cut into many small diamond shaped pieces. Damiano says it is important to cut the curds and not break them, so they will knit back together. The diamond shape allows more surface area, and helps the curds stick together. As the curds are cut into smaller pieces you can see them start knitting together (see photo below of cheese curd disc on Damiano’s hand or the side of the copper vat- this was not formed or strained it was simply removed with a ladle, and allowing gravity to unite the proteins).

- The heat is raised to 54-55 C (122-131F) and the curds continue to knit together and the cheesemaker uses their hands and eye to judge when the cheese is ready. This is the critical time to never walk away from the vat. The curds rest at 55 C for 60 minutes- the bad bacteria die due to time and acidity “like pasteurization but not as high a temperature”.

- Once the curds are ready, the cheese curds are gathered in the linen cheesecloth to separate them from the whey.

- The drained curds are divided in half to make “the twins”, (two wheels are made in every vat, every once in awhile if there’s not enough milk they will make a solo wheel in a vat) and the whey is drained off.

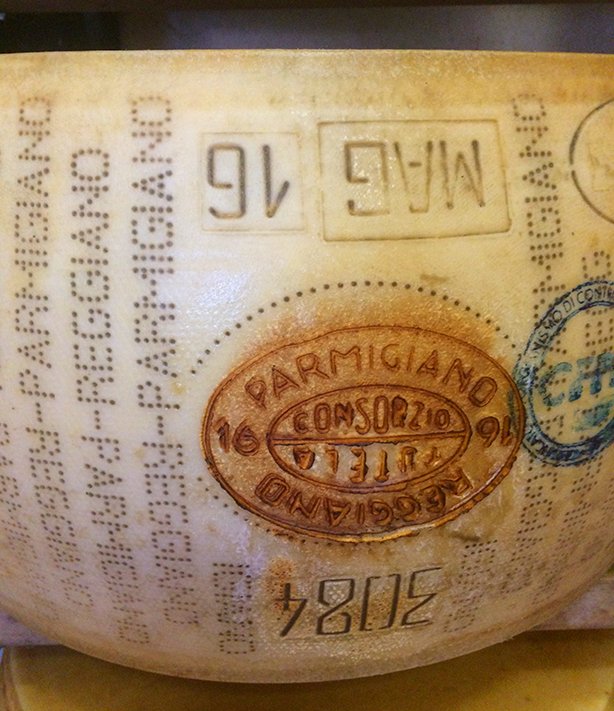

- Once the wheels are formed they will be put into the frame that imprints it with the recognizable pin dot markings along with the farm number and month of production. There are also QR codes on a casein label put on every wheel that can be used to provide full traceability on the cheese.

- The wheels rest for three days in a humid room, prior to going swimming in the brine pools. There are a couple different versions of these pools- some have the cheese floating freely in shallow pools, where they are only partially submerged and they must be rotated on a regular cycle. Other pools are much deeper, and the cheese are put on metal racks that allow them to be fully submerged into the brine water. The amount of time in brine varies with each producer but it is in a range of 18-23 days for the farms we visited.

- After removal from the brine, the wheels are moved to a larger aging room where they will be allowed to age and develop for at least 12 months. They can be considered Parmigiano Reggiano only when they are over 12 months of age and have been tested. If they pass the test they will be branded, or if they do not pass the rind on the wheels will be removed to prevent anyone from passing this cheese off as the real Parmigiano Reggiano.

A Centuries-Old Process

Many of the processes of the cheese making go back hundreds of years. The evening milk is left to sit overnight, and it is not refrigerated (held around 18 C /64.4 F). There are many different types of bacteria in the milk that are naturally occurring—they are impacted by the feed they eat, and the handling of the milk, as well as the local environment. We asked Damiano about leaving the evening milk to sit overnight at room temperature. He explained that if you had subpar milk the the outcome wouldn’t be good, which is why this isn’t done for all cheese production, but only when the milk is superior quality. The milk has a mix of bacteria that helps the cheese develop, and as the cream rises overnight it naturally removes bacteria they don’t want in the milk.

There remains within the cheese making of Parmigiano Reggiano® a blending of knowledge, traditions from the past combined with present day technology advancements. There’s still a strong reliance on the skill and craft of the cheesemaker in the process to convert a perishable liquid milk into an incredibly tasty wheel of certified Parmigiano Reggiano that continues to develop flavors and provide nutrition many years into the future. Even though we aren’t as dependent on our ability to preserve foods without refrigeration as our ancestors were, I can’t help but admire the care and skill that were developed to provide sustenance throughout the year, and the strong commitment to quality and flavor that continues to this day.

Ravarano is a coop- and the individual farmers own the dairy. Damiano is paid by the farmers to make the cheese. He also owns the cheese shop and buys the cheese that he sells in the shop. Prior to us importing the cheese with the help of Rogers Collection, all of Damiano’s cheese had been only sold in Italy. We’re thrilled to have his cheese on our counter at the Deli—stop by for a taste!

Zingerman’s Art for Sale