Did you know?

Not all Parmigiano Reggiano cheeses are the same. We’ve scoured Italy for the best of the best!

Thanks to the good work of the Consorzio Parmigiano Reggiano®, founded in 1934, we’ve found 5 excellent cheeses to offer. The Consorzio—and every farmer and cheesemaker who’s a part of it—have long been committed to making and purveying a top-quality product. All the cheese that bears the P-R name must meet very high standards. 339 dairies are authorized to make the cheese, using milk from over 3000 farms and over a quarter million cows. Over 50,000 people work to make it all happen. The entire process is regulated. The cheese must, by law, be produced in the designated districts of Parma, Reggio-Emilia, Modena, a small part of Mantua and another small slice of Bologna. The feed for the animals must come mostly from the farms themselves; a small amount can be brought in, but still has to have been grown in the region. The milk must come only from the region and is never pasteurized. Each producer uses partially skimmed evening milk, combined the next day with whole milk from the following morning. Just raw milk, salt, and calves’ rennet are used. All the cheeses are made in carefully spec’ed copper kettles. Every cheese dairy is closely inspected and every single cheese is checked by the Consorzio experts before it can be given the prestigious Parmigiano Reggiano Consorzio “firebrand” and have its side panels show off the now famous “pin dots” that spell out its name.

Quality aside, this project is a concerted and focused effort to achieve long-term, sustainable excellence. How to take our Parmigiano Reggiano offerings to championship levels!

What makes the difference from one cheese to the next?

Well, pretty much everything you can imagine. While Parmigiano Reggiano is properly and elegantly well-branded as a broad category, the truth is that there are so many variables that it’s actually a marvel that this still hand-crafted, authentically artisan cheese actually comes out well as often as it does. Here’s some of the big factors we can control for in our selection:

The Cheeses

The Crème de la Crème; The Best of the Best

Right now, we have five different offerings in house. At times, we might have more; at other times, less. But our drive, our commitment, our new belief is that we serve you best by having a nice range of top notch, terrific tasting cheeses from different dairies, of different ages, different milk sources, and of course, different flavors. Try them all together to really appreciate the contrast. Or taste them at the counter before you buy in order. Or if you’re feeling generous, order up a few pieces and send them to a parm loving friend. Unless they’ve lived in the home region of Italy, you’ll make their day. I know my own Parm consumption has increased dramatically since we started getting these exceptional cheeses!

The Process

Making the cheese

Not long ago, I visited another Parmigiano dairy, under the guidance of Signor Giovanni Morini from the Consorzio. About five foot ten with soft gray eyes, he wears a black felt hat, an odd match with his long white inspector’s coat. His looks remind me a lot of Jason Robards in his later years as an actor. Signor Morini has been involved with Parmigiano most of his adult life. “I worked as a cheesemaker. I started out helping in the dairy when I was ten years old,” he told me. Now he’s in his early fifties, with kids of his own. His kids are less enthusiastic about the cheese than he is. In fact they hardly eat it. “But I eat their share for them,” he says with a smile.

As we walk through the dairy, Sig. Morini recaps the entire process for me. Production of Parmigiano Reggiano takes place today pretty much as it has for centuries. The evening milk has been skimmed then blended with morning milk. The mixture is warmed gently until it reaches 91°F when liquid starter culture and rennet are added. The Consorzio requires that the starter be the old-fashioned type, made on-site in each dairy using some of the previous day’s whey, which has been allowed to ferment overnight. In essence, this works in the same way a sourdough starter for bread would with newly made dough. Regulations also require use of natural, animal rennet from calves. (By contrast most cheeses today are made with lab-produced starter cultures and rennet substitutes.)

Eight to twelve minutes later the liquid milk has been converted into a seamless, cream-colored curd, looking a lot like a giant cup of custard in the copper kettle. The cheesemaker gently begins to break it, in the process starting its separation into curds and whey. The more the curd is broken up, the more the whey is separated. The kettle is stirred mechanically, while being heated at about 131°F, for about thirteen or fourteen minutes to allow for further separation of curd and whey, and enhance the development of acidity. When the proper acidity level is reached, the stirring ceases. The curd settles to the bottom of the vat where it knits into a single solid mass.

The decision to move from one stage to the next belongs to the casaro. To a certain degree the decision is based on science: temperature, acidity levels, etc. But in part, it’s still an art. The cheesemaker feels the curd, squeezes it, tests its resilience in the palm of his hand. And based on this sensory input he may, or may not, move the curd to the next phase. Says Signor Morini, “The fingers of the casaro are critical. Bad timing can be fatal.”

He then takes a pair of two-foot-long sticks and ties each to a corner of a large square piece of cheesecloth. The cloth is dipped into the whey to moisten it, then slid underneath the solid curd. At this point the cheese looks something like a large round of fresh white mozzarella. The cheesemakers pull the curd, still dripping copious quantities of whey, from the vat, where it’s then suspended and allowed a brief bit of time to drain. When it has attained the appropriate level of firmness, the casaro cuts the single curd mass in half with a long knife, leaving behind a pair of cheeses. The Italians refer to them as gemelli, or twins. One is the “boy,” the other, of course, “the girl.” The newly separated cheeses are resubmerged in the whey then tied into their own individual cheesecloths.

The cheeses are removed from the vat and sit in straight-sided forms lined with cheesecloth, to let them drain for most the day. The cloth is changed every sixty to ninety minutes. Bad management at this stage can cause a high acid layer to form on the outside of the cheese, in which case, the locals like to say that the, “cheese was sleeping.” “Actually,” says Signor Morini laughing, “it means ‘the casaro was sleeping.’”

In the evening the last cloth is removed. White plastic sheets—which have the words “Parmigiano Reggiano” in pin dots stenciled up and down their sides—are slid between the forms and the still impressionable cheeses. This step was added in the mid-sixties, part of the Consorzio’s never ending effort to differentiate Parmigiano Reggiano from its many imitators. When the cheese arrives for sale to the public the pin dots provide branding the consumer can watch for to be certain that the cheese is authentic. Plastic stamps are also inserted into slots inside the plastic to mark the cheese with month and year of manufacture and the dairy’s number. When all is set the mold is pulled tight and the printing on the inside of the mold begins to impress itself into the sides of the new cheese. The next day the plastic is removed and replaced with a stronger stainless steel mold.

After a few days of restful draining the young parmigiani are moved down to the cellar under the dairy. There they are placed into baths of salt brine. The young cheeses float, bobbing in the brine like a flock of orderly rubber ducks at a carnival booth, are turned regularly to ensure even salt distribution. “Rolled” is actually more appropriate since they are suspended on their sides in the brine. The brining works by process of osmosis (the same process my mother used to tell me would never get me by in my schoolwork). The salt in the liquid naturally pulls moisture out of the young cheeses, and in its place the brine in the vats enters the curd. This is the only salt that is added to the cheese. The young wheels will spend 24 to 28 days down in the brine, after which they will be removed to the storage rooms. After the cheeses are removed from the brine, the salt continues to slowly make its way into the heart of the cheese; all told it takes a good six to eight months before the salt completes its crystalline journey to the center of the wheel.

On to the Aging

“There are no shortcuts in life. You cannot acquire knowledge in a year, nor can you expect a real Parmesan to ripen in a day.”

—Edith Templeton, English writer, c. 1950

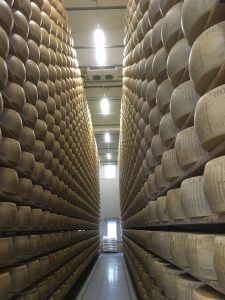

Every time I enter a Parmigiano aging room I feel like Aladdin discovering the treasure cave of Ali Baba. Everywhere you look big beautiful wheels of Parmigiano Reggiano surround you. Thousands of shiny golden wheels stacked on pine shelves that fill the room from floor to thirty foot high ceiling. It’s easy to imagine that each room holds well over a million dollars worth of cheese.

The cheeses will spend anywhere from twelve to twenty-four months or more in the maturing rooms. Most make their way out in eighteen to twenty four. Temperatures in the aging rooms are pretty much left to the swings of nature. As is the case with Balsamic vinegar and Prosciutto di Parma these seasonal temperature changes are an important part of the cheese’s ultimate flavor development.

Typically, the maturing rooms are not “refrigerated” in our sense of the word. These days, though, they are “air conditioned,” which allows the cheesemakers to avoid extremes of heat and cold. In the summer the rooms are hotter (about 64-72°F) and more humid; the cheeses sweat profusely, and enzymatic activity is high. In the winter the wheels are cooler (about 50 to 60°F), resting more comfortably. Throughout, the cheeses are brushed regularly to avoid molding, and turned frequently to insure even moisture distribution. During the aging they will experience approximately a twenty percent reduction in weight; newly brined cheeses enter the aging rooms at about 100 pounds, and emerge in the end at less than 80. The cheese loses about 11 percent of its weight in the first year; then about 7 percent in the second year. If it’s aged longer, it will likely lose another 4 percent in the third year.

Checking the Cheese

When the cheeses enter the aging room they have a six-inch wide oval impressed into their sides. This is where they will be stamped with the seal of the Consorzio if the inspectors give them the thumbs up to be sold as proper Parmigiano Reggiano. The inspectors travel in pairs, I assume to insure the authenticity of their work and minimize any opportunity for graft. Using a small metal hammer, the inspectors tap the top and sides of each wheel, much as pediatricians check children’s reflexes by tapping their knees. They tap the cheese, listen, shift a few inches to the right, then quickly hammer again, until they have tapped their way right around the entire form. A well-made wheel will have a consistent, solid sound to it. If a cheese has physical faults or gaps in its body the hammer blows will evoke a hollow, uneven sound that the inspector’s expert ears will quickly detect. Typically 9 to 10 percent of cheeses doesn’t make the cut, in which case big X’s are slashed through the Parmigiano Reggiano logos embedded in its sides. (These cheeses are sellable as common grating cheese, but never with the name Parmigiano Reggiano and they are never exported.) If it does pass its boards, it is rewarded by being branded with the Consorzio emblem, basically the Parmigiano version of the Good Housekeeping seal of approval.

There is an annual competition amongst these well-trained tappers. “It is very amusing,” said Dr. Mario Zanoni, the Consorzio’s “sensory analysis guru.” I envision a dozen dour men in white coats standing seriously, tapping in time to test their skills and their wits. Maybe one day it might be added to the Olympics?

In all seriousness, the skill of the inspectors makes the tapping an effective way to identify cheeses with faults in them. But, best I can tell, all the hammering in the world is not of much help when it comes to picking the best tasting Parmigiano. And this, from my perspective, leads to one of my frustrations with the Consorzio grading system. The inspection focuses on finding faults, not fine flavor.

Granted, now and again, the inspector will actually probe a cheese with a thin metal augur. With a round eye on the end from which it is held, the inspector uses the file to slide out a tiny sample of the interior paste of the cheese. A quick sniff of the sample will reveal much about the flavor and character of the cheese. Any fault will be immediately noticeable to the trained nose. This aromatic assessment, and/or actual tasting, are really the only ways I know to tell whether a wheel of Parmigiano actually tastes great.

Sure if the cheese has made it this far in the process, it won’t ever be bad—I’ve never purchased a piece of Parmigiano Reggiano that was less than a five or six out of ten on the flavor scale. But the problem comes when you want to find cheese that’s going to hit eight, nine or ten. From a consumer’s—and even from a retailer’s—standpoint, there’s just no way to know. We’re at the mercy of the market. As a retailer buying seventy-pound wheels at a time, the trial and error system isn’t all that economically viable. An importer may have a decent idea of what they’re buying. But even they haven’t tasted every cheese. Many of them barely taste it at all. Which means that trying to find the most flavorful pieces of Parmigiano can be a trying task.

Flavor

The key to assessing Parmigiano maturity is not strictly one of simple chronological comparison. In fact, the actual age of the cheese seems to be secondary. Like makers of one of the region’s other great foods, Balsamic vinegar, the key—locals insist—is the flavor, not the number of months a cheese has been matured. To get some insight into what a given wheel will actually taste like, locate the stamp on the side of each wheel which tells you the month and year of its “birth.”

Once you know its origin, start the calendar rolling. To really be ready for optimal eating, Parmigiano must be aged through two summers. Summer is when the cheese sweats, concentrating its flavor and expelling unneeded moisture. It’s also when the natural bacterial activity in the cheese is at its highest, meaning that the summer months make a disproportionately high contribution to the quality of flavor in the finished cheese.

With this in mind, Italians divide the calendar into three Parmigiano parts:

- January through April is known as the “head.” Cheeses made during these months will be ready most quickly because they get two summers of aging in only eighteen or twenty months.

- May through August is said to be the “body” of the year. Because these wheels get started in the aging rooms some time in mid-summer, they often need more than eighteen months to be properly matured.

- September to December is known as the “tail.” By definition, cheese made in this part of the year almost always needs nearly two years maturing time.

There are cheeses in the aging rooms that are three, even four, years old. Personally I like the intensity of a lot of these cheeses; the flavors are concentrated, mouth filling. They have a different role to play than the soft gentle flavors of the younger cheeses. Regardless of the age of the cheese, the locals’ taste in Parmigiano is very definitely for delicate cheese. By their standards, the best Parmigiano Reggiano is sweet and mellow. They adamantly insist that they like it “dolce;” sweet, gentle and mild. As they see it, Parmigiano should always complement, never overwhelm. Most of the locals turn up their noses at stronger cheeses, most of which they ship to the south of Italy where the preference is, indeed for cheeses with more pronounced flavors.

The Crystals

One of the magical things about biting into a piece of really well-aged Parmigiano-Reggiano is the feel of those tiny sharp crystals crunching on your tongue. Many folks mistakenly take these to be salt crystals, but they aren’t. During the aging, the proteins in the cheese are broken down into smaller nutritional units (peptones, peptides and free amino acids in case you were wondering). Some of these amino acids—particularly tyrosine—are naturally converted into a crystalline structure. Their presence is one of the signs of a well-made cheese and long aging.