Learning to Move In and Around Different Worlds

Photographers, circles, Edgewalkers, and important new insights

One of the things I love most about the experience of regenerative studying is how other insightful people’s perspectives can help me to suddenly understand things I’ve been around for ages—and understand them in wholly different and intriguingly inspiring ways. It’s very much what Tomasz Trzebiatowski, photographer and editor of the terrific FRAMES magazine, wrote this week about the renowned Belgian photographer Harry Gruyaert. Gruyaert, who turned 84 in August, was a street photography pioneer half a century ago and a colleague of the remarkable Joel Meyerowitz, whose photographic work and writing have inspired me any number of times over the years. Writing about Gruyaert’s unique style, Trzebiatowski says:

Gruyaert’s work has always been thrilling in the way it articulates a particular way of seeing. He has had the good fortune to travel widely, and whether he’s taking images in Belgium or Morocco, London or Paris, airports or alleys, it’s not that he sees things differently. He emphasizes differently.

And this is, indeed, what happened to me in studying the work of another photographer who’s also a filmmaker, the Vietnamese American artist Tuan Andrew Nguyen. A single comment by Nyugen, a small part of a much longer conversation he had with Art21—the group that produces the PBS documentary series Art in the Twenty-First Century—offered me a wholly new framework with which to look at what makes our lives, organizations, and countries healthier, livelier, more creative, and ultimately more meaningful.

In the interview, Nguyen talked about his own life experiences, including the moving around the world he has done over the course of his nearly 50 years on the planet. He shared this thought that stopped me in my tracks:

I don’t think that being in between worlds is something that limits us. Learning to understand different worlds is going to be a skill that helps us to navigate a very precarious future. That liminality actually empowers people.

I had never considered the connection Tuan Andrew Nguyen made in that comment until I heard him say it. I’ve been turning it over and over in my mind, and, a week later, I agree. His statement makes total sense. My belated, Nyugen-inspired glimpse of the obvious, my interpretation of what I learned from him, is that as we look ahead to the second quarter of the 21st century we would be wise to work with this understanding front of mind:

People who regularly move through multiple worlds with a modicum of comfort and effectiveness have much higher odds of doing more and better work in the world.

Two months ago, I wrote a lot about the import of edge in organizational health. In that essay, I reminded myself and maybe you as well that the edges of an ecosystem—not any imagined hierarchical center—are where most new creative ideas, cool initiatives, and organizational innovations tend to come from. Which means, then, that the more edge we create in our companies and our communities, the healthier we are likely to be. Instead of pulling back from the edge, putting up walls around a theoretical center to “protect” us, we would be wise to shift the focus to creating more edges, and then spending a significant portion of our time in them. Edge work like this won’t always be fancy, but it can be exceptionally effective. Get out of the office, call customers, answer phones for a few hours, work the front door if you have one, riff freely on routines, read widely, engage enthusiastically on the periphery. To use a baseball metaphor, it’s useful to skip the skybox sometimes and sit, instead, out in the center-field bleachers, sipping beer from paper cups and squinting to see home plate—things look a lot different from the 23rd row in right-center field than they do from the front office.

This essay is, in a sense, a follow-up to that first one on edge. In the spirit of Harry Gruyaert’s good work, I’m taking something that I know well and emphasizing a different element of it. Spending time in and near the edges of organizations, philosophies, natural ecosystems, and more is awesome. But better still, as I now see thanks to Tuan Andrew Nyugen, is that taking things further, engaging with the edge, and then deciding to keep going into less familiar, or at times wholly unfamiliar, territory helps us enter a different world and often really wonderful new worlds.

Tuan Andrew Nyugen’s work is all about this approach to life. He is constantly moving between worlds and always doing it with grace, sensitivity, and skill. As the bio on his website states:

Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn’s practice explores the power of memory and its potential to act as a form of political resistance. … Through collaborative endeavors with various communities throughout the world, Nguyen sets out to cultivate and empower these strategies enacted and embodied by his collaborators.

Born in Saigon in 1976, Nyugen came to Oklahoma three years later with his parents and brother. From there, he went west to the University of California, Irvine, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in fine arts in 1999. He followed it five years later with an MFA at CalArts. A few months after that, he decided to move back to Vietnam, where he still lives now. He settled in Ho Chi Minh City, in part to reconnect with his roots. He also reconnected with his grandmother, a poet and writer, who passed away not that long ago at the age of 102. Nyugen’s work has always been about learning to create collaboratively, something we attempt to do here in the Zingerman’s Community of Businesses (ZCoB), too. We both believe that the more good people can weave into the creative circle, the better things will go at every level.

The fact that I gained this new insight about the import of moving regularly between worlds is evidence to offer in support of Nyugen’s belief. Tuan Andrew Nyugen is not a big name in the food business, nor has he written about leadership, anarchism, or any of the other subjects I engage with so regularly. Nyugen’s comments were shared from a country I know relatively little about, in a city I’ve never been to, in relation to a line of work that is way outside the realm of what I do every day. And yet, as you can tell, engaging with the new world of Tuan Andrew Nyugen got me thinking. And then writing. Journalist Kenn Sava says of Harry Gruyaert’s art, “His photographs will make you stop and wonder—what’s going on here?” And that’s pretty much what happened to me when I encountered Nguyen’s words about moving through multiple worlds.

Being able to understand and engage with multiple worlds, I’ve realized in reflecting on all of this, is a big part of what makes Zingerman’s what it is as we approach our 44th anniversary this winter. I can now see that even in those awkward early years after we opened the Deli in 1982, both Paul (for those who don’t know, my business partner since the beginning) and I were able to move from one world to the next and do reasonably well in any of them. I don’t mean that we couldn’t have done it better, or that we didn’t mess up many times, or that we don’t have a lot to learn. I just mean that from the get-go, we have each in our odd and awkward ways been reasonably adept at engaging with people from circles very different from our own. We relate fairly well to people of pretty much any age, race, religion, or walk of life. We have both, for as long as I can remember, been as comfortable talking to dishwashers as to department heads at the university. We happily work with bakers and busboys and also with bankers and big-time business leaders. We have both traveled a lot. We read a lot, and we go to a wide range of conferences. We move from one world to the next pretty regularly. It’s not uncommon for me to meet with someone who was just released from incarceration, and then move straight into spending time with some new business owners who are eager to understand how to incorporate. My passport doesn’t get stamped each time I do it, but the truth is that I’m crossing multiple borders almost every day.

Paul and I were, I can see in hindsight, what the team at ZingTrain would call “unconsciously competent”—we gave it little thought, and we were just good at doing it. Next time I talk about what makes us who we are at Zingerman’s, I’m going to tell the audience that this ability is embedded in the essence of the organization. Countless others here in the ZCoB are adept at doing it as well! And this ability to shift rather fluidly between worlds is now the norm for me and many of the people who work here.

Both Harry Gruyaert and Tuan Andrew Nyugen have traveled all over the world. Here at Zingerman’s, we do it a lot, too. We travel to study food, understand where our products are coming from, and, as in the case of Food Tours, for a living. That said, while movement between worlds may certainly include going to other countries and exposure to cultures of all sorts, a plane ticket is not a prerequisite for making it happen. We can enter new worlds without leaving our bedroom. Reading books about topics we don’t usually engage with is one way to do it. We also do it when we talk to people who have backgrounds that are wholly different from our own or beliefs that we may not share. It can be done, too, by experimenting in different areas of insight, or regenerative studying in specialties that are significantly different from our own. This is, I see now, what is coming out of my collaboration with Michael Dickman, which involves learning about poetry and how to put it to use in my everyday life. You can enter new worlds by taking classes in new-to-you fields of study, or, if you’re a city kid like me, by taking time to walk through local fields and pay close attention to what you find.

While I have embraced this new-to-me understanding, I know that moving fluidly and regularly between worlds is not the way much of the world wants to work these days. In fact, it’s the opposite of what seems to be happening around us in many settings right now. Far too many people are reacting to understandable bouts of discomfort by trying to minimize contact with other worlds. Historian Heather Cox Richardson wrote a whole column a couple days ago about how super-wealthy people are withdrawing from the world the rest of us inhabit today, and how a similar thing happened a hundred years ago during the Gilded Age. We have leaders who are working to wall off, to ban books, to forbid “foreign” philosophical frameworks, to remove people who don’t “look right,” “sound right,” or “write right.” All of this is happening, right now, right in front of us.

It seems that, out of understandable insecurity and anxiety, many people are living out something that my friend, the Irish writer Gareth Higgins, and his coauthor Brian McLaren have written about in The Seventh Story. As I wrote about a few years ago, the book is about the “seven stories” that are lived out regularly by human beings like you and me. The most rewarding option on their list is “the seventh story,” a story in which “love is the protagonist.” It’s certainly the story we are working hard to live in here in the ZCoB. Love is in our mission statement, our 2032 Vision, and our hearts. The authors also detail the six “other” common but destructive stories that dominate in many societies. Two stories that Gareth and Brian lay out in the book are what seems to be happening around us: The Isolation Story, where “we get away from them,” along with The Purification Story, where “we get rid of them.” Both stories reduce access to other worlds.

Nyugen’s theory is pretty much the exact opposite of isolation. When we seek to engage regularly with other worlds, we invite others in so they can experience our work and our world at Zingerman’s. And rather than getting away from others, we are regularly trying to spend time in their worlds to learn about what they do, as well as why and how they do it. This kind of positive work doesn’t have to cost a lot. It can be done quite effectively simply by spending time in different neighborhoods, studying an unfamiliar language at the local community college, reading books about philosophies that are wholly new to us.

Listening to TED Talks can be helpful, too. Fifteen years ago, the Turkish-British writer Elif Shafak, about whom I wrote a fair bit a few weeks ago, did a TED Talk in which she shared a good deal about her upbringing. Born in Strasbourg, France, her parents got divorced when she was still a young girl, and a young Shafak then moved to her mother’s homeland of Turkey. There she was raised by her mother and her maternal grandmother. Her mother, Şafak Atayman, was a westernized, modern Turkish woman. After graduating from college, she became a successful diplomat who worked for many years in the foreign service. By contrast, Shafak says, her grandmother was “more spiritual, less educated, and definitely less rational. This was a woman who read coffee grounds to see the future and melted lead into mysterious shapes to fend off the evil eye.” A young Elif watched as people came to her grandmother, who was not trained in modern medicine, to be healed of any number of ailments. Surprised by the effectiveness of grandmother’s seemingly very old-school healing work, Shafak asked her for the secret. Her grandmother’s suggestion was to “Beware of the power of circles.” As Shafak explains:

From her, I learned, amongst many other things, one very precious lesson—that if you want to destroy something in this life, be it an acne, a blemish or the human soul, all you need to do is to surround it with thick walls. It will dry up inside.

Now we all live in some kind of a social and cultural circle. We all do. … But if we have no connection whatsoever with the worlds beyond the one we take for granted, then we too run the risk of drying up inside.

Our imagination might shrink, our hearts might dwindle, and our humanness might wither if we stay for too long inside our cultural cocoons. Our friends, neighbors, colleagues, family—if all the people in our inner circle resemble us, it means we are surrounded with our mirror image.

Isolation—either individual or collective—is an idea that, to some, can sound good. I get it. I’m an introvert who regularly leans into having time alone, so I’m all for solitude. Used well, for reflection, regrounding, reading, and recharging, alone time can lead us to engagement with other worlds of knowledge, culture, and understanding. In other words, it can be conducive to connection rather than implicitly about isolation. But alone, on its own, will not likely get us where we want and need to go.

I mentioned the other week that Shafak calls our current era “The Age of Anxiety.” It’s an apt assignation. She also, though, refers to it as “The Age of Division.” The same walls that appear to protect also restrict. And as Shafak says, “It worries me immensely, seeing the walls rise higher and higher.” Walls limit access. They reduce the amount of edge, and they make it harder and harder to freely and fluidly move around any number of different “worlds.” As Shafak says:

Ironically, [living in] communities of the like-minded is one of the greatest dangers of today’s globalized world. And it’s happening everywhere, among liberals and conservatives, agnostics and believers, the rich and the poor, East and West alike. We tend to form clusters based on similarity, and then we produce stereotypes about other clusters of people.

Shafak cites the wisdom of Lebanese American poet Khalil Gibran, who said, “I learned silence from the talkative and tolerance from the intolerant and kindness from the unkind.” She transposes those lines into a learning for our present-day challenges:

From populist demagogues, we will learn the indispensability of democracy. And from isolationists, we will learn the need for global solidarity.

So, what do we need to do this “world-traveling” work? And how do we do it more effectively? Well, I’m just learning. Let me know what you think. Here’s my opening bid:

- An abundance of humility

- Dedication to dignity

- A generous spirit of generosity

- A worldview rooted in positive beliefs

- Consistently high levels of hope

- An endless cache of curiosity

- A healthy sense of self that allows us to learn, engage, and share without worry that we will lose ourselves in the process

People who don’t have these skills remain, of course, good people. But without these skills, it’s harder to engage outside our comfort zones effectively. Those who do have these attributes are far more likely to move freely to and from multiple worlds, learning well from each in the process. I’m talking about people like Harry Gruyaert, Tuan Andrew Nyugen, and Elif Shafak, people who move from one world to the next with regularity. They have learned how to take pain—which, of course, we all have in our own ways—and turn it into art that helps them heal and helps the rest of us lean into and learn from their creative expression. For example, one of Tuan Andrew Nyugen’s best-known works was a collaborative project entitled The Unburied Sounds of a Troubled Horizon that included turning spent U.S. Army artillery shells into beautiful hanging bells that make a symphony of lovely sounds.

In a metaphorical sense, that seems to be what the team at Emerge (which includes philosopher and chess Grandmaster Jonathan Rowson) is trying to do on a bigger scale: Take what has gone wrong in the world, learn from it, and combine it with what has long been right, to write about new approaches to the future. It’s an intriguing organization that seems to be involved in this work of moving through, into, and around multiple worlds, reflecting regularly on how to blend traditional wisdom with new insights and ideas. Of the present moment, they write:

We are at a fork in the road. Two kinds of possible futures for humanity are likely: further entropy and collapse, or the emergence of a higher-order system that is more complex and elegant than our current one.

It seems clear to me that the people Tuan Andrew Nyugen was talking about in the interview that sparked all this thinking—those who, like Nyugen, can move well between different worlds, those who learn well from others and who can embrace and engage with difference and diversity, all the while learning to be truer to themselves—will almost certainly fare well in the rest of the 21st century. They are the ones who can lead us towards Seventh Stories, and towards learning, dignity, humility, and more health for more people.

From the outside looking in, writer and speaker Judi Neal seems to be one of those people. Neal, who earned an advanced degree in organizational behavior at Yale University, has already given a name to people who walk in many worlds. She calls them—or us, I might be wiser to say—“Edgewalkers.” I love it. Neal explains:

I am passionate about organizations and teams understanding the value that Edgewalkers bring to the workplace. Usually people who have Edgewalker qualities are seen as strange and they are often marginalized. But Edgewalkers are the ones that see what others cannot see, and they have a commitment to making the world a better place. … We need our Edgewalkers more than ever in this uncertain and unpredictable world. The old ways of doing business no longer work, and Edgewalker leaders, and Edgewalker organizations can show us a new and better way.

Edgewalkers, to my sense of it, are the kind of people Tuan Andrew Nyugen was talking about. They spend a lot of time in and around the edges, and they regularly move past the edges and explore other worlds as well. With each metaphorical trip abroad, they add to their already wonderful wealth of knowledge. Over 10 or 20 or 30 years of practice, what an effective Edgewalker can enable is impressive. This description of Edgewalkers feels like a fair way to frame the work we do here in the ZCoB. It’s true, too, of many of the people I learn from and write about here in this enews. Elif Shafak, Tuan Andrew Nyugen, Little Mazarn, Pharoah Sanders, Sarah Harris from the band Dolly Creamer, adrienne maree brown, Harry Gruyaert, and so many others. Neal shares a quintet of critical characteristics that all Edgewalkers have in common:

- Self-awareness

- Passion

- Integrity

- Vision

- Playfulness

All five resonate with me. Neal also shares five skills that we can practice that help us to become more adept at walking the edges with excellence instead of anxiety. Again, I can relate to all of them, and they show up in the adaptive approaches each of us uses:

- Sensing the future. A healthy sense of where we’re going, per what Tuan Andrew Nyugen shared up top.

- Risk-taking. One example is Elif Shafak’s willingness to write about topics that are “taboo” in Turkey.

- Manifesting. To me, it sounds like what we call “visioning” here in the ZCoB.

- Focusing. The ability to actually implement learnings from the other worlds we have visited.

- Connecting. The decision to value others, to see their uniqueness, and to draw out the best in them.

Folklorist Henry Glassie, who led the Turkish Studies program at Indiana University, has spent his whole life engaging with different worlds. His work has taken him to Ireland, Turkey, Nigeria, the Appalachians, and Bangladesh for significant amounts of time. Insights abound in Glassie’s work, but this particular quote really caught my attention in the context of edges:

The creation of the future out of the past [is] a continuous process situated in the nothingness of the present, linking the vanished with the unknown, tradition is stopped, parceled, and codified by thinkers who fix upon this aspect or that in accord with their needs or preoccupations.

The ability to move fluidly from present to past to future and back again, over and over, is another way to effectively engage with different worlds. I realize we are actively teaching everyone in the ZCoB to do all three:

- The past by studying food, writing a lot about history, and staying committed to traditional food. This is not always what organizations do. Of her homeland, Turkey, Elif Shafak says, “Nations don’t always learn from history … If anything, we [Turks] are a society of collective amnesia.” The past, for those willing to use it though, can be a powerful tool for managing more effectively in the present moment. Tuan Andrew Nyugen says he “explores memory as a form of resistance and empowerment, emphasizing the power of storytelling as a means for healing, empathy and solidarity.”

- The present by teaching mindfulness and energy management, appreciating and cultivating great service, staying dedicated to finding joy, and actively looking for beauty. We work hard to help people learn to be in the moment.

- The future through our visioning work, which challenges us to regularly move our minds into the future. Tuan Andrew Nyugen’s short dystopian sci-fi film, A Dream Of The End At The End Of A Dream, uses an imagined future to send a message to us in the present moment.

This work of traveling regularly between worlds is, I can now see, a big part of what makes the books and music of my friends at Indigenous Resistance so compelling for me. They are all based on engaging with worlds and worldviews that most of us in the West would not otherwise know about. They are Edgewalkers extraordinaires. They share the histories of indigenous cultures in Africa, elucidate elegant insights from Ethiopian spiritual leaders, and visit Mongolian record shops. Through their records and books, they explore the writing of Native American activists, East African anarchists, and so much more. Each of their works makes clear what Tuan Andrew Nyugen knows—that it’s all about healthy connections with, dignity for, and active learning from other worlds.

Reading each of the Indigenous Resistance books has been a wonderful example of regenerative studying at its best. They have exposed me to an incredible array of new, always inspiring, often anarchist sources. They guide me from Uganda to Ulaanbaatar, Senegal to South Dakota, and everywhere in between. They introduce me to Jamaican musicians and Mongolian shamans, Native American poets and North African spiritual leaders, revolutionaries and writers, and so much more. They bring me into contact with a plethora of places and people I might likely never have known on my own. Their most recent print publication even has a photo of the ancient stone in Mongolia where the word “Turk”—now Elif Shafak’s homeland—was carved into writing for the first time.

This passage from Indigenous Resistance’s new book, Mongolian Dub Journey, seems to sum up much of this traveling-between-worlds work:

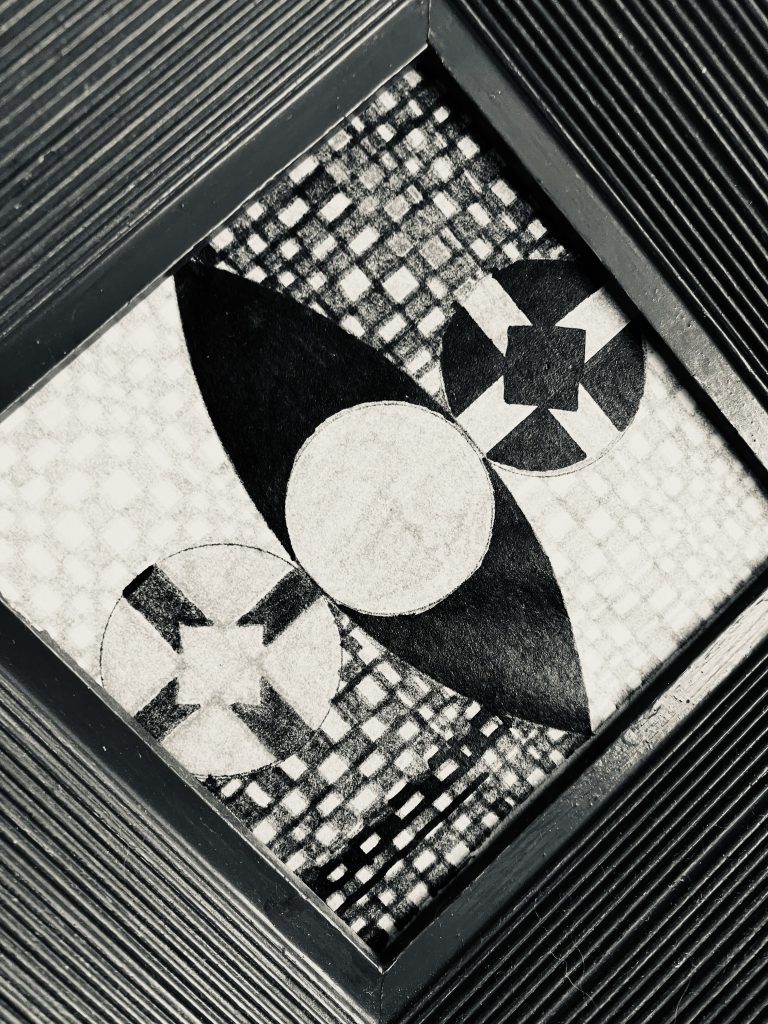

When one sees boundaries dissolving between ‘genres’ and art forms, this has always been very inspirational for me to observe. This is because I believe that is in these spaces of dissolved boundaries … where we can create the space to be truly creative and forge new pathways.

The people who move between worlds in this way, the Edgewalkers among us, are setting the positive, collaborative, and inclusive pace for the 21st century. It’s work we can all do. I smiled when I saw these words in a recent retrospective write-up about Harry Gruyaert’s work at the Helmond Museum in the Netherlands:

The origin of all his work is the world around us.

Look around. Listen. Breathe deep. Be ready. Other worlds, with a wealth of beauty and wisdom, await.

Explore other worlds

P.S. If you want to move through a whole range of different culinary worlds in a matter of hours, consider coming to one, or both for that matter, of the two “Best of 2025” tastings I’ll be doing at the Deli next month. The first one is Tuesday, December 2, at 6:30 pm, and the second one is the following Tuesday, December 9, at 6:30 pm. Hope to see you there!