The Power of Joy to Transform Our Organizations

Cut-up poetry and prioritizing joyfulness even in the face of pain

In 1951, the American Surrealist artist, author, and poet Dorothea Tanning, working in the very special light of the cabin that she and her husband, the artist Max Ernst, had built in Sedona, Arizona, completed a 2-by-3-foot oil-on-canvas painting. She called the piece “Interior with Sudden Joy.”

The painting, like all of Tanning’s work, and for that matter, her whole life, is remarkable. The title, though, is what caught my attention. Joy, for a whole range of reasons that I’ll share below, has been very much on my mind.

Tanning once opined that “art has always been the raft onto which we climb to save our sanity.” Her image of an interior existence being regularly brightened by sudden bursts of unexpected joy is, well, giving me joy, and also a bit of much-needed sanity while I work to cope with the rather frightening flow of current events in the greater ecosystem around us.

Joy was not something I remember being taught about as a child, but I learned later in life that joy matters far more than I would ever have imagined. While it’s not taught in too many business school settings, joy is actually an essential element in the making of a healthy organization. In fact, joy fits nicely into #12 on the list of Zingerman’s Natural Laws of Business:

Great organizations are appreciative, and the people in them have more fun.

With that understanding in hand, I have worked hard for many years now to make the title of Tanning’s painting come alive—to have an interior life regularly punctuated by bursts of unplanned joy! And, as best I can, help make similar joyful experiences a regular reality for everyone who works in our organization, and for all of our caring customers as well.

Half a century after she finished the painting in Arizona and a few months after she had turned 83, by then living in Manhattan, Tanning was interviewed by writer Jane Kramer for a piece that was later published in The New Yorker. Near the end of the essay, Kramer asks Tanner about the flow of her writing, in particular her poetry. “Well, sometimes,” Tanning explains, “an idea keeps rolling around in your head, or a pair of words, but you don’t really know what it is. It has to emerge.”

I can absolutely relate. Thanks, in good part, to stumbling on the title of Tanning’s painting, joy emerged as the topic of this essay after rolling around the rocky corners of my mind for the last couple of weeks! In these challenging times, as we try to figure out how to lead effectively, living out Tanning’s title is, I believe, an essential act of existential health. It’s true for each of us as individuals and for our organizations as well.

It might seem strange—or, to some cynics, sort of silly—to focus any of our limited attention on joy when there are so many other issues that seem more pressing. I, of course, take the opposite approach. Joy has the power to transform organizations and the lives of the people who are part of them.

My friend Rich Sheridan, co-founding partner of Menlo Innovations here in Ann Arbor, literally wrote the book on joy. Actually, he wrote two: Joy, Inc. and Chief Joy Officer. I have found what Rich writes to be right on: “The journey to joy at work is personal. It has to be. You want a job or an organization that brings you joy.” Even if they’re not conscious of it, people want to frequent joyful businesses and live in joyful communities and countries. And while the news may not reflect it much right now, joy can and does remain a healthy, positive, uplifting, smile-evoking, eye-opening act of resistance.

If you doubt the power joy can have on a national level, check out the history of Chile. Frank Greer, the founding partner of the progressive global consulting firm GMMB, worked extensively with the fledgling Chilean democracy movement that went on to unseat the longtime brutal dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet through an effective electoral process back in the late ’80s. In a retrospective he wrote two years ago this coming February, Greer noted:

The slogan “Chile, joy is coming” signified a bright future with democratically elected leadership, the rainbow logo illustrated the many parties working together and the inspiring music captured the hope of the nation. … [These efforts] brought joy and democracy back to Chile!

If joy can change a country, I’m confident it can effectively alter our organizations as well. Whether it’s in companies or countries, joy is an effective strategic tool for anyone who wants to improve their quality of life and bring more dignity and democratic practices into play. NYU history and Italian studies professor Ruth Ben-Ghiat writes, “Joy is precious and noble and also the basis of effective anti-authoritarian strategy.” In 1988, roughly 2.5 million people in Chile (nearly a third of the country’s voters) participated in what was widely known as the “March for Joy.” On October 5th of that year, the pro-democracy program won nearly 55 percent of the vote while 43 percent went to the military dictatorship. The government had the guns and a grim determination to hold to power; the democratic opposition, though, won the day with joy front and center. I smile now, realizing that Lucinda Williams’ classic song “Joy,” released a decade later in 1998, summed up the whole situation:

I don’t want you anymore, you took my joy

You took my joy, and I want it back!

The power of joy has been effectively exercised far closer to home as well. In the second week of December 2009, writer Toi Derricotte, who grew up in the Detroit neighborhood of Hamtramck, posted a poem entitled “From the Telly Cycle.” Dedicated to her beloved pet fish that had recently passed away, it leads with the line “Joy is an act of resistance.” That poetic pronouncement has since been used by others, but it seems that Dericotte was the first. It would go on to become a significant slogan of what came to be called the Black joy movement. Professor of African American Studies Mei-Ling Malone makes clear that “Black joy is an act of resistance. The whole idea of oppression is to keep people down. So when people continue to shine and live fully, it is resistance.” Joy, it turns out, is both more fun and a powerful force for change—both individually and collectively— at the same time.

All that said, these are not, I know, the easiest of times in which to focus on and feel joy. When anxiety is high, when costs are rising, and consumer confidence is dropping, when national leaders are known to be lying, when innocent people are getting iced right in front of our eyes, it would be easy and understandable to feel down. Some days, some hours, and some other times, too, I most definitely do. My determined focus on finding joy, though, helps me get through. It keeps me focused, determined, and resilient. It makes my eyes light up, and my smile grow wide, no matter what is going on in the world around me. Joy, for me, is an essential ingredient in resilience and resistance both. Without joy, my internal ecosystem suffers; with it, everything goes better. Joy doesn’t just immediately make all the challenges we face go away, but it does give me the energy to deal with them far, far more effectively.

Having spent many years now studying the subject, both in my own life and in our organization, I can say with confidence that you can feel the difference joy makes. This little story from last week reminded me how much of a difference.

Two weeks ago tomorrow, I cracked a tooth. My caring dentist came in on her day off to take a look. Ten minutes into treating me, she delivered the bad news: The tooth had already been filled twice before; there was really no way to save it. Taking it out, and then the rather intimidating insertion of an implant, she said, would be next. The following Thursday afternoon, I had the tooth extracted. It’s not the most painful thing I’ve experienced, but it wasn’t all that much fun either. Pain followed, as expected. Being like jazz musician Pharoah Sanders, Sarah Harris of the band Dolly Creamer, and the other inspiring folks I wrote about a few weeks ago, artists and leaders who keep going even in tough and awkward times, I went back to work that evening. Since it wasn’t going to be any less painful sitting at home, I figured I’d just power through at work, where the bustle of a big dinner rush at the Roadhouse could take my mind off it. I gritted my teeth (metaphorically, given the circumstances), got centered, smiled, and decided to make it a great evening anyway.

A little before nine that night, I found myself in conversation with a nice young couple, first-time guests from Ohio who were dining at a table across from me while I worked on the computer. Turns out I know his parents, both longtime chefs from Chicago. He and I had a lovely chat, with my tooth—or the spot where my tooth had been—quietly throbbing in my head the whole time. When the couple was leaving—heading to Bay City to see Jerry Seinfeld and likely having a very joyful evening—he and I shook hands and agreed to stay in touch. He looked me in the eye, and with a wonderfully grounded, sincere energy and a big smile, said, “You really seem like someone who just feels so much joy!” Caught off guard in a really good way, I smiled back, surprised that despite it all, joy—not tooth pain—is what came across. In hindsight, I realize that what happened was Dorothea Tanning’s title come alive. Despite the pain from my missing tooth, my emotional interior was immediately made brighter by this sudden burst of joy. And it was a great reminder that, in a focused setting, joy will trump pain. I’m fortunate, I know, to live in a joy-filled ecosystem where situations like this are so much more likely to happen. Not everyone has the same opportunity. I have learned, though, that joy isn’t something that happens to us. Rather, it’s something we need to actively look for. Far more often than most people realize, even in hard times, joy is there for the appreciating. If we don’t pay attention, it passes us right by.

Having spent 25 years learning to tune in and notice joy, I tend to stumble on it almost everywhere I turn. Sure enough, sudden interior joy showed up for me a couple of days after the tooth incident, at about 7 pm on Saturday. During a quiet couple of minutes, I checked my email, where I found a lovely note from my East African friends at Indigenous Resistance (IR). I closed last week’s essay about the import of Edgewalking in the modern world by citing the exceptional way that IR exemplifies the willingness to engage with intriguing and interesting worlds, ideas, cultures, and more. The regenerative study I had engaged in to write the piece had already brought me a great deal of joy. But, as Dorothea Tannin’s writing reminds me, there is more to almost every story than it might seem. She would regularly tell anyone who was listening to stay open and curious, “Behind the door, always another door…” And, sure enough, another door into this already good story about Edgewalking unexpectedly opened up for me. My evening was brightened by this email from the other side of the Atlantic:

Greetings in Dub

Hope all is well on your end

I wanted to share something truly amusing with you.

I was reading your latest newsletter and really really loving it, especially when it came to the section with the Vietnamese artist having lived in Vietnam. … I caught the dub of when he’s using artillery shells to make beautiful sounds. But here’s the dub. As I was reading what you were writing about moving between different worlds and edges and actually liminal is one of my favorite all time words.

I was reading it and thinking my goodness this is so dub, this is so what IR is about. I need to write him to tell him I appreciate it and then I read the next paragraph and it’s about IR.

I couldn’t stop laughing 🙂

I laughed right back when I read it. I couldn’t not smile seeing that the writing had connected. The note touched my heart. Joy, of course, ensued. I think anyone who makes art will be able to relate. We make art for ourselves because we believe in what we’re writing, singing, sculpting, cooking, and so forth. Still, knowing your work has resonated with someone you respect a great deal tends to bring a lovely bit of sudden joy. It’s something I’m always happy to experience!

While experiencing joy is a wonderful thing, its absence can be painful. Dorothea Tanning grew up in the very conservative community of Galesburg, Illinois. It was, apparently, a rather joyless place. Journalist Richard Howard reports that Tanning would say, “It was a life unsweetened by culture,” and, as Tanning told it, “Where nothing happens but the wallpaper.” If my friend Shawn Askinosie is correct that our life’s vocation is nearly always the healing of our childhood wounds, Dorothea Tanning delivered in style: she went on to live a remarkable, productive, vibrant, joyful, and joy-filled life until she passed away in the winter of 2012. Tanning was 101, and making art right up until the end.

In 1920, at the same time that Tanning was turning 10 in central Illinois, on the other side of the Atlantic, the Jewish-Romanian anarchist poet Tristan Tzara had just celebrated his 24th birthday. The previous year, Tzara, who would later turn out to be one of Tanning’s artistic influences, had left his native Romania and moved to what one could consider the spiritual opposite of Galesburg: Paris. There, Tzara turned out an abundance of edgy, intriguing artistic work.

Tzara, who was instrumental in founding the Dada art movement, is a joy for me to study. Tzara was born Samy Rosenstock in the Romanian town of Moinești. At the time of his birth, roughly half the town’s population was Jewish. Thanks to my friend, Alabama-based Romanian poet Alina Stefanescu, for turning me on to Tzara’s work. Anyone who knows me even moderately well will immediately recognize how regenerative study—especially reading about Tzara’s life—has evoked an enormous amount of joy. After all, Romanian Jewish artists and anarchist poets are not a dime a dozen. Tzara, like Alina Stefanescu and Dorothea Tanning, is one of a kind. How could I not be fascinated by a guy who once wrote that “morality is the infusion of chocolate into the veins of all men”?

In 1920, Tzara penned a piece called “How to Make a Dadaist Poem.” It was a day-to-day way to take the Dadaist philosophy that he helped pioneer, and put it to work. Tzara put the instructions in poem form:

Take a newspaper.

Take some scissors.

Choose from this paper an article of the length you want to make your poem.

Cut out the article.

Next carefully cut out each of the words that makes up this article and put them all in a bag.

Shake gently.

Next take out each cutting one after the other.

Copy conscientiously in the order in which they left the bag.

The poem will resemble you.

And there you are—an infinitely original author of charming sensibility, even though unappreciated by the vulgar herd.

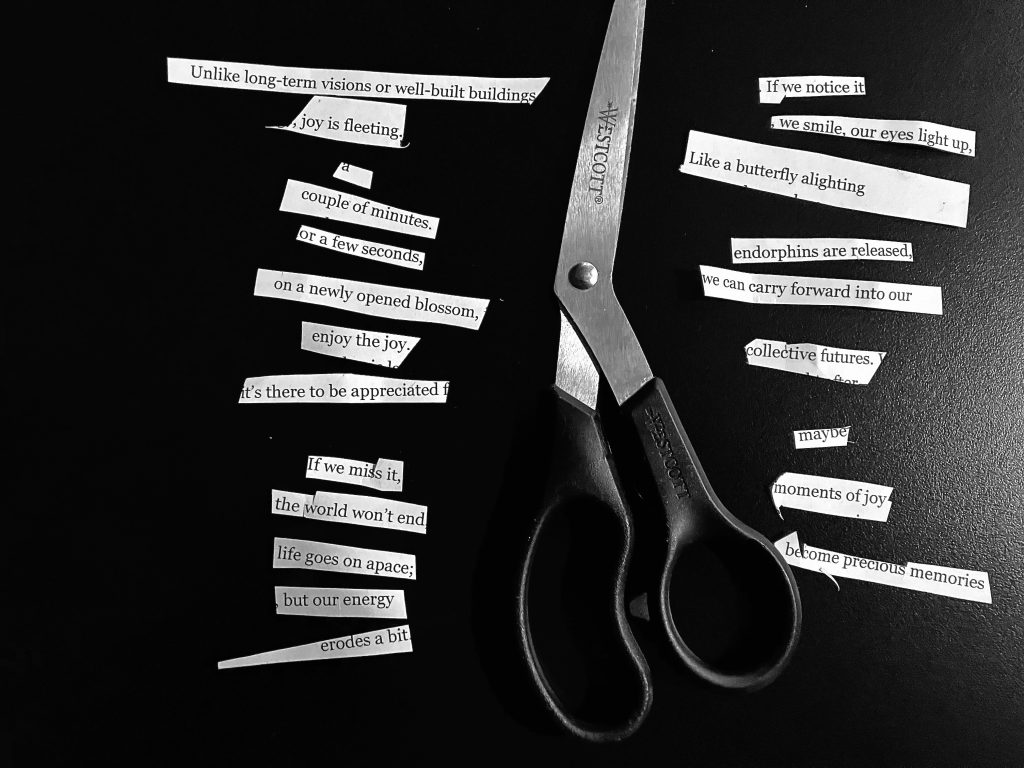

While it may sound silly, a whole series of rather famous people have used and advocated this “cut-up” technique. Writer William Burroughs is one. David Bowie is another. In fact, the famous line “I’m an alligator” in Bowie’s early ’70s classic “Moonage Daydream” seemingly came from practicing Tzara’s method. Given my recent work around poetry and desire to lean into Dorothea Tanning’s idea of an interior filled with sudden joy, I challenged myself to follow Tzara’s recipe.

To get going, I printed out the piece I wrote on joy in this newsletter a few years ago. The beginnings of what I created from the cut-up are in the photo above, but here is the whole joy-evoking poem. To be clear, other than the title, all the words were already on paper—all I did was cut and then arrange them in an order that resonated. Sure enough, joy ensued as I assembled (or, I suppose, reassembled) the pieces:

A Bit of Romanian Dadaist, Jewish, Anarchist Poetic Joy for the 21st Century

Unlike long-term visions or well-built buildings

joy is fleeting

a

couple of minutes

or a few seconds,

on a newly opened blossom,

enjoy the joy

it’s there to be appreciated.If we miss it,

the world won’t end

life goes on apace;

but our energy

erodes a bit.If we notice it

we smile, our eyes light up,

like a butterfly alighting

endorphins are released.

Maybe

moments of joy

become precious memories.

we can carry forward into our

collective futures.

In his “Dada Manifesto 1918,” Tzara reminds us that “everybody practices his art in his own way.” Performer Patti Smith happens to be particularly good at it. In a recent interview with the New York Times’ Ezra Klein, Smith put the current state of the country in perspective and showed how she connects to joy in the face of adversity:

Despite everything that’s happening in the world and everything around us and any frustration or helplessness we feel or betrayal we feel, we have to remember it’s also all right to feel the joy of being alive and feel the joy of your own possibilities. Even in the face of the suffering of so many people around us.

Smith, who Spin Magazine called “a cross between Tristan Tzara and Little Richard” after an interview in March 1979, also reflects on her long career as a performer and poet: “I feel grateful because people are still interested in this work that was committed half a century ago. It’s a lot of joy.” Of the many loved ones she’s lost over the years—her husband Fred, her brother Todd, her lover and friend Robert Mapplethorpe, her longtime pianist Richard Sohl—she says, “They remain within me. And I can still access joy.” Providing more evidence that those who do well in life can find joy in the face of adversity, she continues, in an expression and explanation that sounds remarkably like what we might say here in the ZCoB:

Despite that [loss], I feel also the joy of celebration—and happy to be here, happy to be physically able to do it, to feel my voice is strong and that I can give the people, as authentically as I can, the experience of the record as a new experience every night. I want everyone who comes in wanting a special night to leave feeling that it was a special night.

Speaking of special nights, I am reminded with great regularity that joy will almost always appear at some point, and usually in ways that I least expect it. I just have to be paying enough attention to notice it.

To wit, on a rather mundane mid-autumn Tuesday evening, I ran into a family with two young daughters. The youngest, maybe 10 years old, was celebrating her birthday. When asked where she wanted to go for dinner, she chose the Roadhouse. That, to me, is one of the best compliments a restaurant can get. Curious, I asked what she had for dinner. With a big smile on her face, she rattled off the elements of her birthday meal: “The salmon. And mashed potatoes. And spinach. It was really good.” Lo, that I had been that into food when I was her age! For me, that sort of thing is far more meaningful than an award. Joy at its hospitality-focused best.

About 10 minutes later, dining room manager Zach Milner, who was expediting that evening (assembling orders, checking for quality, and sending them out into the dining room), asked me to run a lone fried chicken leg over to table 206. When I got to the table, I saw a new mother with a relatively young infant. The child was holding another chicken leg tightly in her fist and awkwardly but passionately eating it. She was far too young to talk, but the message was clear. The mother smiled and said, “I gave it to her to try a bite. She’s never eaten chicken. And she ate the whole thing!”

Sometimes, of course, joy comes in these beautifully upbeat and innocent moments. But it’s of equal import when we’re struggling with a serious issue and unsure of how to move forward. Nearly a century ago, Tristan Tzara gave some advice that our whole country—me included, of course—could take to heart. “Let us try for once not to be right.” Instead, we can listen with open hearts and remember that joy is a part of living a good life, even in stressful situations. We can, in that context, skip the lectures and instead lean in and then learn some more. If we’re paying attention, the odds are pretty high that some joy will ensue. Choosing joy, even in the face of adversity, is one of the best ways we can lead positive change.

Last weekend, the campus newspaper at the University of Toronto ran an article by student Augustus Crysler-Hill entitled “Indigenous Joy, The Backbone of Colonial Resistance.” In it, Crysler-Hill writes:

I believe that it’s important to recognize Indigenous joy as an essential part of colonial resistance. … I consider the joy and humour that are present in Indigenous cultures to be resistance in multiple ways. … By expressing this joy, Indigenous peoples show that they are still alive and well and reject the societal narrative that Indigenous peoples are simply victims of the past.

Indigenous joy is not only important in the context of resistance, but also due to its healing and connecting qualities. Laughter serves as a connection between family members and is key to Indigenous communities. It gives relief in times of hardship and allows our people to discuss traumatic events.

In the metaphorical organizational ecosystem pamphlet I’m partway through working on, butterflies are akin to joy. They show up in abundance in healthy ecosystems and are diminished on land that is not healthy. And because butterflies flutter past so quietly, we need to pay careful attention. If we don’t, the joy flutters past, and our lives are a bit poorer for having missed it.

If butterflies are joy, a lovely one landed on the back of my metaphorical hand as I looked deeper into Tristan Tzara’s life. It turns out that Tzara was, for a number of years, also active with the Symbolist movement. As a young man, Tzara—at that point, still in Romania and known as Samy Rosenstock—even helped cofound a Symbolist magazine. As you may remember, symbols have really been on my mind a lot in recent months. Tzara, it turns out, also used butterflies as a symbol in the Dadaist philosophy he helped to frame, noting that “Dada covers things with an artificial gentleness, a snow of butterflies.”

On the 5th of May, 2012, Patti Smith, who I now keep thinking of as “the Tristan Tzara of punk,” played her first show in Mexico. It was held in what had been the home of artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Journalist Guillermo Urdapilleta writes that Smith, who had turned 65 six months earlier, performed “with evident joy.” Her joy, it seems, was contagious. By the end of the evening, Urdapilleta reports, the audience had become “a joyful mass with a wonderful vibe.”

The night before the show, dealing with pain from a fall the previous day, the staff at the house had suggested that Smith sleep for a bit in Kahlo’s bed to rest her body. While she was sleeping, she dreamed of a poem. The next morning, she wrote it down, calling it “Noguchi’s Butterflies,” inspired by the butterfly collection that Kahlo had hanging on the ceiling above her bed. The butterflies were gifted to Kahlo, many years earlier, by architect Isamu Noguchi. The two met 90 years ago this year, in 1935. They were briefly lovers and then friends. The butterflies were, Noguchi said, something Kahlo could look at while she lay in bed with the pain she suffered from polio. These lines, pulled out of the center of Patti Smith’s poem, show what joy makes possible:

Within my sight

All pain dissolve

In another light

Transported thru

Time

By the butterfly

Symbolism, of course, makes me think about apricots, which I’ve come to see as a symbol of dignity and democracy. I think apricots can also help us find joy when we’re facing adversity. I’ll leave you, then, with this little joke that brought me a bit of joy when it popped unexpectedly into my head a couple of weeks ago! It brought me a good bit of sudden interior joy, and I hope it does the same for you.

Q: What do you call a group of dignity- and democracy-loving musicians that get together for an impromptu session?

A: An apricot jam!