Creating Companies in Which Education Is for Everyone

Lessons from the Paris Commune of 1871

Scholar Henry Giroux, who turned 82 two months ago last week, wrote recently that “Americans have forgotten what democracy is about.” What follows is an exploration of one way we might help ourselves, and the people we work with, to remember. To be clear, it’s not about what happens in Washington. This is about our workplaces. It’s about what we can all do to help everyone in our organizations better engage in the kind of free thinking that any effective democratic construct calls for, whether it’s in a small company or a large country.

To put it another way, this essay is essentially about class. Not in a class-war kind of way, though. This is about the work the Zingerman’s Community of Businesses (ZCoB) does to offer an array of insightful classes. Classes about everything from food philosophy to finance, customer service to courageous conversations. The key here is that the many dozens of classes we offer are available to everyone in our organization. As one coworker once told me,

I have never before talked to the owner of a company I was employed at about my personal life goals. The owners of Zingerman’s not only reinforce them, they pay me to take classes to make them happen. Literally, they pay me to better my personal life. That’s totally crazy.

After decades of doing this, it’s very clear to me that all this class work we do alters our business for the better and improves the lives of the people who work here. I am also confident in saying that it strengthens our community and our country. Lately, though, I’ve noticed that their significance—and the fact that we open them to everyone in the organization, regardless of job title, age, or seniority, and pay them to attend—is far greater than what I’d assumed before.

In a piece published two years ago in The Paris Review, the remarkable writer Hanif Abdurraqib—who I admire greatly for passing on the publicity that might come with moving to the East or West Coast, as many artists do, and instead staying rooted in his hometown of Columbus, Ohio—commented on the state of the country. In his words, our society “is obsessed with punishment, particularly for the most marginalized.” As I reflect on what dominates the news and current national trends, what Abdurraqib wrote resonates. It is a difficult reality to get my mind around. As Sarah Harris from the band Dolly Creamer sings in her song “Live in There,” “We’re in a movie that does not move me.”

There are many places, of course, that we can collectively help those who have less. As psychologist Abraham Maslow pointed out in his oft-referenced Hierarchy of Needs, food, shelter, and safety are always the most critical concerns for anyone living on the edge of physical survival. Beyond that, though, Abdurraqib’s insightful comment made me curious:

- What would it look like if, instead of prioritizing punishment and retribution, our society was instead obsessing over education and learning?

- What if businesses across the country were willing to teach finance and philosophy and Servant Leadership and the like to everyone in an organization, from entry-level staff to upper-level managers, helping them think like leaders and engage with complex issues in creative and challenging (in a positive sense) ways?

- What if many of those classes were not just about teaching specific job skills but rather about helping people learn to think? What if they helped people at all levels of the organization grow into themselves and become actively engaged with the sorts of philosophical issues that are usually left to upper-level leaders to grapple with in more formal settings? These kinds of learning opportunities are rarely offered to folks on the front lines. What if making them readily available to all became the national norm?

I realize that we’ve been trying to answer these questions in our day-to-day lives at Zingerman’s for many, many years now. It’s impossible to isolate the impact of all those classes from everything else we do, but I have no hesitation in saying that it’s hugely significant. Without our constant focus on learning and teaching, we would be a very different organization. The classes we teach are, in a sense, another entrée into the benefits of the regenerative studying I wrote about a few weeks ago. They support the growth and development of many dozens of us—probably more, actually—who work here every year!

Our decision to offer so much training came out of our deeply-held belief that people want to learn, that when people are thinking more clearly and cohesively, they feel better and do better; and that everyone in the organizational ecosystem—customers, neighbors, vendors, and community—benefits in the process. We did it because, to us, it just seemed to be the right thing to do. It was intuitive. That said, there’s recent data to back up our long-standing belief. This past spring, the Harvard Business School wrote that “Research shows that companies experience a 17 percent increase in productivity and a 21 percent boost in profitability when employees receive targeted training. … Teams feel valued, empowered, and motivated. This sense of purpose fuels a culture where growth, collaboration, and innovation flourish.”

The idea of constant learning is deeply embedded in the essence of our organization. We like to learn. We want to understand why things are the way they are now and also how they got that way. History major that I am, I’m happy to say that nearly every class we teach includes some history. I will share a whole bunch of that next Tuesday night when I teach my annual Best of 2025 tasting class at the Deli.

Speaking of history, Henry Giroux started his career in education as a high school history teacher. He warns that “The dominant culture actively functions to suppress the development of a critical historical consciousness among the populace.” History, he reminds anyone who’ll listen, has important lessons to teach us:

We need to realize that if you can’t learn from history, you go beyond the cliché of simply repeating it; you find yourself in a place of danger in which historical consciousness and its relevance turns to historical amnesia. … The United States suffers greatly from historical amnesia.

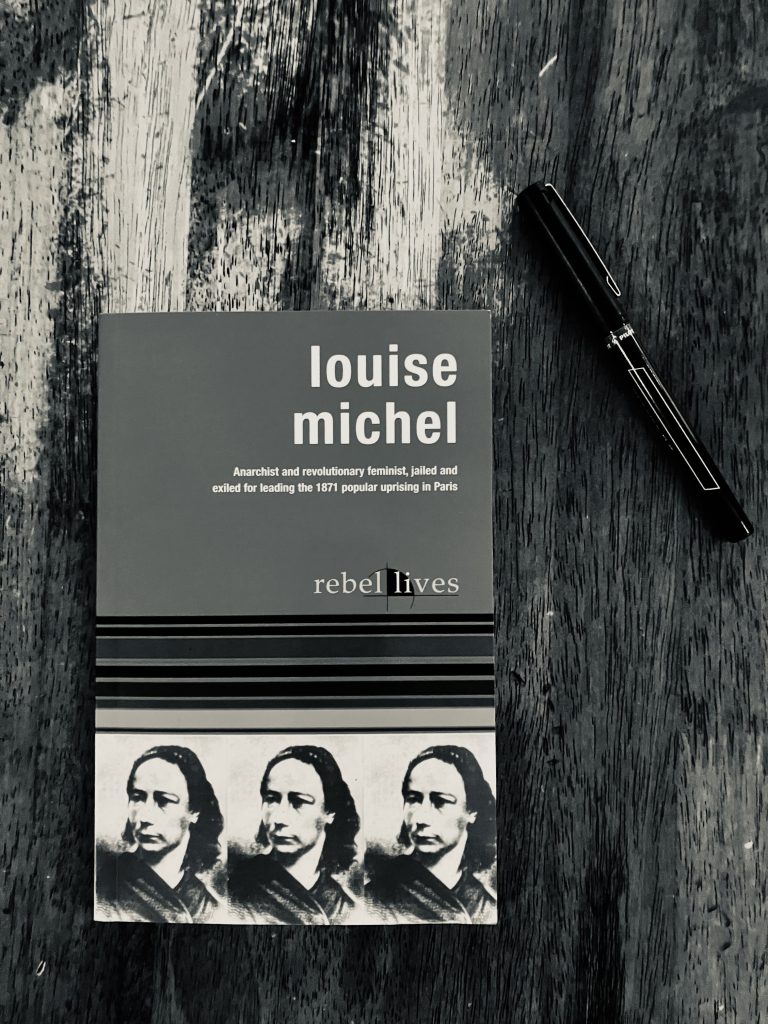

With Giroux’s warning in mind, I’ve had a realization of late. It happened while studying the history of the remarkable 19th-century French activist, anarchist, and educator Louise Michel. More than ever, thanks to her impassioned writing and speaking on the subject, I can see the import and impact of our efforts to make classes and other forms of learning widely available to everyone in the organization. In her memoirs, published in 1886, Michel wrote that the powers that be in society “do not want to share the sweetest thing of this old world: knowledge and learning.” For Michel, education was as important as eating. As she put it, learning about anything from painting and poetry to physics and philosophy should not be the province of a privileged few. “Art, like science and liberty,” Michel wrote, “must be no less available than food.” To Louise Michel, education was liberation. And, in a sense, I can see now that in a quiet, easily missed-by-many way, offering so many learning opportunities to everyone who works here does just that.

Louise Michel was born in 1830 in the town of Vroncourt, in the Haute-Marne, in the northeast part of France. The daughter of a poor single mother living in a rather remote region, she loved both animals and learning from the time she was a child. In 1861, when she was 31, Michel moved to Paris, and in 1865, she opened a progressive school there. The mid-19th century was an era in which thousands of people were leaving their villages, abandoning old craft trades to take newly created-in-the-Industrial-Revolution factory jobs in cities. These were workplaces where what mattered most was one’s ability to persevere through mind-numbingly repetitive and physically challenging tasks. Wealth was created, but most of the world was worse off for it. As historian Mark Cartwright explains:

The workforce became much less skilled than previously, and many workplaces became unhealthy and dangerous. Cities suffered from pollution, poor sanitation, and crime. The urban middle class expanded, but there was still a wide and unbridgeable gap between the poor, the majority of whom were now unskilled labourers, and the rich, who were no longer measured by the land they owned but by their capital and possessions.

Writer Chip Bruce has picked up on Louise Michel’s magic. Bruce, who’s very active in a program called Democratic Education in the 21st Century, writes:

She was an early practitioner of what I’d call inquiry-based learning. She was a continual learner. … As a schoolteacher, she used methods promoted in the progressive education movement (which came much later): interaction with objects such as flowers, rocks, and animals, studies outdoors, and scientific methods. … Michel wanted students to learn to think for themselves, just as she did herself and encouraged others to do throughout her life.

Louise Michel had the radical belief that the flow of learning should be reversed. Instead of being done only for those at the top of society, Michel believed that creative education ought to be available to anyone who was interested. She imagined a future in which art, learning, and science would belong to all people, not just a privileged few. As she explained:

Genius will be developed, not snuffed out. Ignorance has done enough harm. … The arts are a part of human rights, and everybody needs them.

A century and a half or so after Louise Michel said that, there is still a great deal of wisdom in her words, wisdom that any forward-thinking 21st-century organization of any size would be able to benefit from. Classes, books, conferences, libraries … all can be made as available to people in front-line jobs as to those in formal positions of power. As Louise Michel wrote in her Memoirs, charity was not the answer. “What we do want,” she wrote, “is knowledge and education and liberty.”

Carol Sanford, who passed away a year ago this month in her mid-80s, was, I believe, as radical in the world of modern business philosophy as Louise Michel was in mid-19th-century France. Sanford, like Louise Michel and Henry Giroux, was always very direct in her criticism of mainstream practices. As she put it: “The way most companies manage their workforces is bad for business. Not coincidentally, it’s also bad for people and for democracy.”

Among the many things Sanford helped me to understand is the import of what she calls “indirect work.” While most businesses—both in Louise Michel’s era and our own—focus primarily on work that will directly and immediately impact financial results, operational effectiveness, or both, Sanford was adamant that those efforts must be accompanied by those that are wholly indirect. As she explains in her book Indirect Work:

Indirect work is inner work … It is about change inside each of us, in the ways we perceive and understand the world and our roles and responsibilities within it. … Profound change rarely comes from direct interventions in the world. Rather it comes working indirectly over time, helping people engage consciously to develop their own understanding, motivations, aspirations, and will. All sorts of human endeavors can benefit from this approach.

The kind of broad educational activity that we do here in the ZCoB is a great example of what Sanford is suggesting. It’s hard to prove exactly how a new staff member attending a class on self-management increases sales or how a sandwich maker taking a class on personal visioning will change our organization. Still, per what Carol Sanford is saying so clearly and what Louise Michel understood intuitively, I am confident that it makes a hugely meaningful difference! It helps the people who work here grow as human beings and as leaders, which in turn helps power our organization. As Sanford explains:

Development works on our ability to be awake with regard to ourselves, and this is inherently indirect. … The role of development, to cultivate the capacities for self-observation and conscious choice that enable us to show up as living, creative beings in a living creative world, to be self-determining rather than predetermined.

With Louise Michel’s words in my head, I’ve been realizing anew how important our extensive class offerings really are. And how radical it is that nearly all of these classes are offered to anyone who works here who’s interested. Henry Giroux reminds me how much impact effective education has on the greater ecosystem around us. He’s not just referring to the accumulation of knowledge. Like Louise Michel and Carol Sanford, he’s advocating for social constructs in which self-awareness, empathy, and emotional intelligence are important. As Giroux said in an interview with Julian Casablancas, lead singer of The Strokes: “I want to see people who exhibit two things—a sense of self-reflection and a sense of compassion for others.”As he reminds us, democracies “cannot survive without informed citizens.”

Conversely, I think it’s also right to state the ethical inverse: “An autocratic leader cannot stay in power when its citizens are well informed.” People who have learned to think for themselves, who value their views and the views of others, don’t want to blindly follow a boss who tells them what to do. As Louise Michel said, “The task of teachers, those obscure soldiers of civilisation, is to give the people the intellectual means to revolt.” And that, we can be sure, is not what autocratic leaders of companies or countries would want.

Over our 40-plus years in business, we’ve worked hard to support learning and education in as many ways as possible. One thing we do regularly is send ZCoBbers to various conferences over the course of the year. While we don’t, of course, send all 700 people who work here to conferences every year, we do send a pretty high percentage of people compared to a lot of organizations. The opportunity to learn and make new, creative connections can be incomparable. When I think of all the individuals I have met at conferences where I have been a speaker, it’s kind of mind-blowing. With all that in mind, I try to imagine the experiences that a 26-year-old Emma Goldman had as an up-and-coming American immigrant activist. In September of 1895, at which point she’d lived in the U.S. for about a decade, she was traveling to London to speak at an anarchist conference. After spending 10 days crossing the Atlantic on a steamship, Emma met Louise Michel, a woman who had, by reputation, inspired her for many years. Almost a quarter century earlier, Emma Goldman was a 6-year-old girl in Lithuania when Louise Michel was 41 and fighting on the barricades of the Paris Commune. At the time of the conference, Louise Michel had already had a lifetime of amazing experiences. She celebrated her 65th birthday that year.

The bright moment of the Paris Commune, which started in March of 1871, came to an end that May, when its democracy-seeking supporters were beaten back and then arrested and imprisoned by royalist forces. Writer Adam Gopnik calls it “one of the four great traumas that shaped modern France.” For a few short months, though, anarchists, socialists, and other free thinkers like Louise Michel created a free, non-hierarchically governed city that came to be called the Paris Commune. The Commune got rid of the idea of higher-ups and instead ruled, like the Serbian student movement is doing today, with elected bodies, or what the Serbians call plenums. To this day, the Paris Commune is remembered positively—along with Barcelona during the Spanish Civil War—as an effective, anarchistically oriented, on-the-ground experiment in real-life non-hierarchical governance. And Louise Michel’s courage and creative leadership became a big part of its legend.

In the final weeks of 1877, Louise Michel was put on trial in Paris for her role in the fighting for freedom with the Commune. The opening lines of the trial’s transcript are telling:

The Court. — Your age?

Louise Michel. — Forty-seven.

The Court. — Your profession?

Louise Michel. — Teacher and woman of letters.

While her emphasis on education has clearly impressed me, it did not impress the French court. Michel was convicted and sent to a Paris prison for two years, then put on a ship and sent off to the penal colony on the French-controlled island of New Caledonia. There, Michel again took up teaching, including teaching French to the indigenous Kanak people, not to “civilize” them but rather to give them a tool they could use to advocate for themselves with the French authorities. I wrote a good bit about the value of teaching a few years back, in an essay entitled “Why Leaders Should be Teachers.”

Louise Michel says education’s purpose is “the formation of free men full of respect, and love for the liberty of others.” Looking back on our collective life here in the ZCoB, it strikes me that one of the more radical, impactful things we have done to make our culture what it has come to be is teach a wide range of classes for the people who work here. These classes are, for the most part, open to anyone who wants to go. I’ve lost track of how many we offer, but there are a lot. I lead the Welcome to the ZCoB orientation regularly. There’s Intro to Visioning, where people learn how to write the story of the future they want for their personal lives, work projects, or both. There’s our most oft-taught class, The Art of Giving Great Service. We have a diversity class that we teach diligently every month. There’s a class on Servant Leadership. Two or three classes on Open Book Management. There’s another on personal finance. There’s a class called Managing Ourselves. And everyone who works here has free access to any of the 20-plus online ZingTrain Virtual Workshops. Two weeks ago, right after I had my tooth taken out, I taught the Welcome to ZCoB Governance class to go over the imperfect but very intentional democratic practices we use. These are just the classes I can come up with off the top of my head.

It is, I know, a long list, one that’s likely intimidating to anyone who is considering teaching some internal classes in their own organization. For context, though, remember that we’ve been here nearly 44 years. Even two well-run classes in a small company can make a big difference. We did not create this kind of class list in a couple of weeks. The point is not to have the longest class list in town. It’s to get started, to teach and learn, to get people thinking, to encourage them to ask questions, and to learn to think like leaders instead of waiting for direction.

Right now, this is not the popular mainstream approach. As Henry Giroux writes:

Authoritarian societies do more than censor; they punish those who engage in what might be called dangerous thinking. … Critical and dangerous thinking is the precondition for nurturing the ethical imagination that enables engaged citizens to learn how to govern rather than be governed. Thinking with courage is fundamental to a notion of civic literacy that views knowledge as central. … Thinking dangerously is not only the cornerstone of critical agency and engaged citizenship, it’s also the foundation for a working democracy.

It’s also, I would suggest, critical for creating the kind of organization we envision. Nearly all of those classes, it seems to me, are focused mainly on providing frameworks to help people learn to think for themselves and to develop their own philosophies and worldviews. Informed staff members, as I have experienced them:

- are more willing and able to engage in thoughtful conversation

- are better able to creatively and caringly question the status quo

- learn how to think systemically

- offer insights into how to improve pretty much every part of what we do

- have learned how to lead the implementation of those improvements

- get to know what good meetings are like, which means they learn how to participate effectively in a range of constructive conversations—the kind it takes to run any democratic and inclusive organization

- can handle more complexity and paradox when making decisions in difficult situations

- learn to think like leaders

- learn to self-manage, to be reflective, and to be responsive to requests

- tend to offer constructive ideas and approaches rather than just offering a critique

The impact on the country and our communities is substantial: People who learn these things at work are very likely to practice them when they go home, too. They become more active and effective citizens. They generally do not advocate autocracy. They want to think for themselves, not just blindly follow orders from above. The long-term, big-picture effect is indeed indirect, but over time, it’s hugely impactful, and to me, greatly inspirational. As Carol Sanford writes in The Regenerative Business:

Businesses that foster initiative and self-management change forever the way employees look at the world. When people spend their lives in hierarchical systems with supervisors making decisions for them, their decision-making capacity and their confidence in their own judgement weaken. They become habituated to ceding control and responsibility to authority figures. … By evolving the natural source of human creativity and responsibility, a regenerative business builds more than itself. It grows better citizens and, as a result, it builds a better nation and a better world.

What do we get out of all this? I recently asked one staff member what she thought about the fact that we teach so many classes internally. She smiled a bit and said, “I love it! It’s one of the best parts of working here! I think everyone should take as many of the classes as they can.” A coworker standing nearby who happened to overhear us chimed in, listing the various classes he’s taken, too.

Henry Giroux, who I believe is one of the most important thinkers of our era, said in an interview last year:

If I think about the future, I want to think about conditions that produce the Martin Luther Kings, the Gandhis, that produce massive movements, that produce great filmmakers, great educators, great women, great men who struggle together in a way that is self-consciously benevolent and compassionate. That’s what I want.

Creating an extensive program of internal education is not all it takes to make that happen. But it’s certainly a darned good start. A start that, as Giroux, Sanford, and Michel all highlight, will help create the conditions we need for healthy democratic engagement, both inside our companies and in the country at large! The training and learning work we do in this context today could help someone who’s currently making sandwiches or slicing salami become the next Henry Giroux, Carol Sanford, or Louise Michel. Who knows, someone who leads the work to change our country could be inspired to action by a class you start teaching two or three weeks from now. As Louise Michel says:

That something has never happened before certainly does not mean it is impossible.