Leaning into Magic and Loss

Making magic while living between, in, and around the loss

Last Sunday morning, I was sitting in a sunny corner of a café in central San Diego. Focused and working hard, I was trying to get a bit of writing done before slowly making my way over to the Specialty Food Association’s Winter FancyFaire. I was beginning to explore a hard topic, writing about the death of my friend Manchán Magan, the writer, performance artist, ardent advocate for the Irish language, and amazing human being. I was in the middle of double-checking the date of Manchán’s death—it was October 2 of this last year—when, out of the corner of my eye, I caught sight of something completely and wholly unexpected. I did a double-take, then doubled down, shifted my focus, and looked more closely. Sure enough, it was indeed as I’d imagined: a man walking by with a white parrot perched on his right shoulder.

It seemed almost magical at the time. You certainly don’t see tropical birds like that around these parts very often! Pigeons? Sure. Parrots? Not so much. Maybe, though, this was mostly a matter of my paying attention, not magic per se. If I hadn’t caught the bird out of the corner of my eye, the parrot would have passed by completely unnoticed. Reflecting even further, I realized the two could actually be one and the same. Paying attention can be an entrée into magic-making—especially the kind of magic that Manchán was widely acknowledged to have made in such insightful and thoughtful abundance. Like the white parrot, the magic would have been there no matter what; most people just let it pass without ever taking notice.

To be honest, I almost missed the parrot altogether. I was absolutely not expecting to see one. I’d sat down simply to sip coffee and get some work done, not for exotic West Coast bird-watching. If the omens are accurate, though, it’s a good thing I saw it. A white parrot is said to be a symbol of peace, hope, and new beginnings. All of which we could use right now, given the current state of the country around us.

Speaking of hope and inspiration, 34 years ago this week, Lou Reed released his remarkable 16th album, Magic and Loss. I know that Lou Reed and Manchán Magan might seem like two radically different people, people who might never before have appeared in the same sentence. The former was a Jewish poet and musician, intimately immersed in the dark sides of New York City street life; the latter was deeply drawn to centuries-old nuances of the Irish language and culture rooted in the countryside. And yet, each was, in his own unique way, amazingly adept at making magic, acknowledging loss, and helping others to live magical, meaningful lives of their own.

Like almost all of Lou Reed’s music, Magic and Loss was panned by some people and, at the same time, adored by others. As with most everything Reed has done, those who already loved his work, like me, loved it a lot. David Fricke, writing in Rolling Stone, was clearly in the same category:

Magic and Loss is Lou Reed’s most affecting, emotionally direct solo work since The Blue Mask, a stunning consummation of that album’s naked guitar clamor, the hushed-chapel intimacy of the third Velvet Underground album and the barbed reportorial vitality of Reed’s best songwriting. He offers no great moral revelations and no happy ever after, just big questions and some basic horse sense. “There’s a bit of magic in everything,” he sings at the very end of the record, “and then some loss to even things out.”

Reed’s album title, and that last line of the lyrics, sum up the current state of my mind, the state of the world, and the essence of this essay. There is, like it or not, both magic and a whole lot of loss in the air right now. For me, the loss began with Manchán’s death at the far-too-early age of 55 last fall.

Speaking of New York City, I want to tell you about three thought leaders who are a big part of a new grassroots organization, Friends of Attention, which is affiliated with the Brooklyn-based Strother School of Radical Attention. D. Graham Burnett is a historian, Alyssa Loh is a filmmaker, and Peter Schmidt is a director at the Strother School. They do not, to my knowledge, make records, speak Irish, or write anything about parrots, though Burnett did recently author a book whose title fits this essay: In Search of the Third Bird. Together, the trio authored a powerful and poignant op-ed in the Saturday New York Times. In a piece entitled “The Multi-Trillion-Dollar Battle for Your Attention Is Built on a Lie,” they pushed back hard against the 21st-century mind-as-machine focus on measurement of attention, which many people think of in the context of social media. Here’s an excerpt:

Does it need to be said? We are not machines. Our lives are not data problems that can be quantitatively optimized. And the actual human ability to attend is something much more expansive and much more beautiful than a tool for filtering information or extending our time on task. True attention lies at the heart of personhood: reason, judgment, memory, curiosity, responsibility, the feeling of a summer day, the burying of our dead.

The impact of the trends they are talking about is not insignificant. Burnett, Loh, and Schmidt argue that tragically, this “slice, dice, measure, and make metrics” approach is leading us into ever more difficult and more divisive times. It is also, they add, leading toward the loss of democracy. People with low and divided attention, it turns out, don’t do well in the kind of deep discussion that’s called for in democratic constructs.

The writers do, though, offer an alternative, a way forward one that’s far more grounded and productive than the shape-shifting and attention-splitting that’s increasingly been dominating so much of so many people’s days. They suggest that rather than segmenting attention into milliseconds, we aim for:

A theory of attention rooted in love, care and commitment, an ethics of attention that cannot be sold or stolen. … Call it attention activism or even, as we have come to think of it, a new politics of “attensity.”… The fullness of our authentic human attention, shared with others, is the power with which we make the world. It’s worth fighting for.

At its best, this type of kind, generous, and emotion-centered attentiveness opens a door to making magic. It is absolutely the sort of attention Manchán Magan gave to Irish language and culture. And the results of his hard work and the attensity he poured into it were more than magical.

Manchán, to be clear, didn’t fight for attention. He simply made it happen by doing interesting work, not to mention by being a beautiful writer and a passionate student of the history and language of his homeland. Folks who do work as fascinating as Manchán’s are the sort that other people are eager to tune in to.

I first encountered Manchán, as I did the white parrot, almost entirely by accident and simply by being in the right place at the right time. I was not looking for him any more than I was the parrot. Manchán was simply the very tall, very kind, very smart, and very creative significant other of Aisling Rogerson, cofounder of the very magical Fumbally Café in Dublin. At the time I met him, Aisling and I were just beginning to form what has become a rewarding, long-distance friendship. We’ve been sharing ideas about business and life and food and cooking for many years now. It’s through Aisling that I got to know Manchán’s writing and then, eventually, the man himself.

Manchán came here to Ann Arbor a few years back to visit in person and perform his one-man show about traditional sourdough bread and butter, Aran Im. It’s by reading Manchán’s remarkable writing that I—and many thousands of others who speak no Irish at all—was able to access the amazing, nuanced beauty of the Irish language.

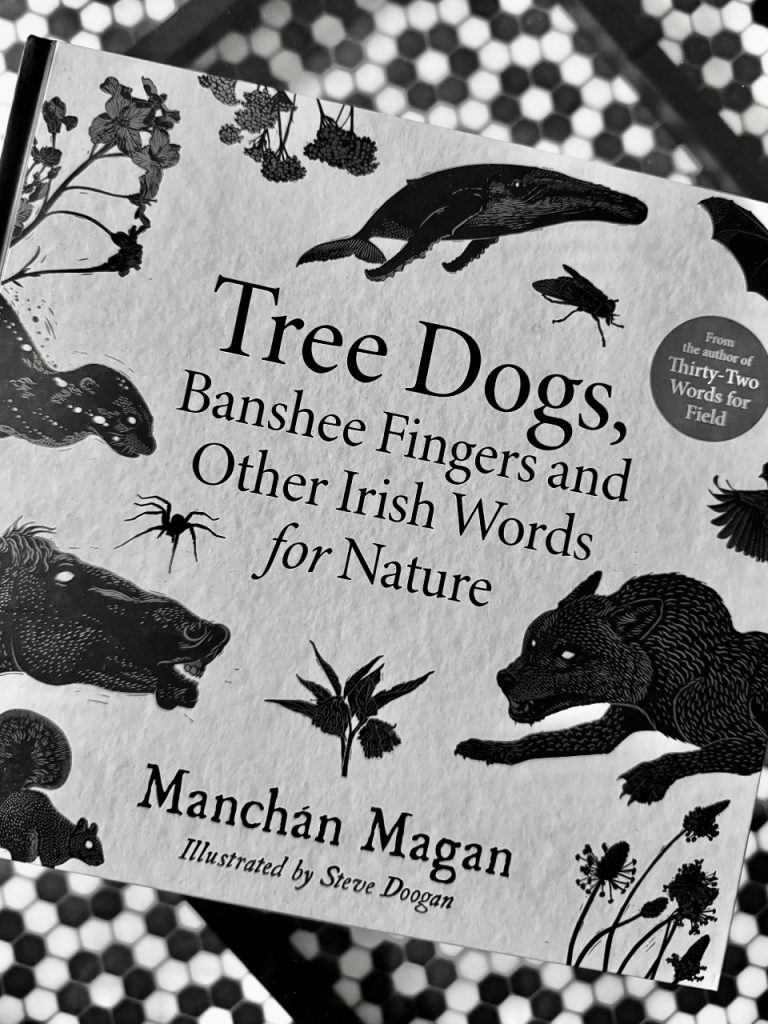

If you have not yet read the man’s books, now would most definitely be a good time to do it. They are the exact opposite of what Burnett, Loh, and Schmidt are urging us to avoid: stuff designed for short-term attention. Thirty-Two Words for Field and Listen to the Land Speak are both fascinating, attention-getting deep dives into the kinds of complex cultural nuances I am so intrigued by. My copies of each are heavily underlined and abundantly bookmarked. I go back to them regularly to revisit the intricate beauty of the Irish language and the history that is so beautifully revealed in them. Manchán’s 2022 release, Tree Dogs, Banshee Fingers and Other Irish Words for Nature, is as amazing as its title sounds!

Many hundreds of tributes to Manchán have been written and spoken, and probably painted and poeted as well, in the three-plus months since he passed. They were often put together by people who knew him far better than me, in their efforts to navigate the pain and loss that accompanies the death of someone so special at the entirely too young age of 50. Ireland is not a big country, and everyone seems to know everyone else! The Irish Times’ obituary for Manchán notes how he “radiated infectious curiosity, cultural nuance, and a sense of the mystical undercurrents in life.” The obituary writer even called him “a national treasure”—rightly, I think—in great part for his work with the language. Musician Liam Ó Maonlaí, from the band Hothouse Flowers, offered that “There was a gentleness to Manchán. He was an otherworldly guy.” Journalist Anthony Murphy, who has himself written extensively about Irish tradition and culture (and is currently writing his next book on a very traditional 1952 Olympia SMS typewriter), added about Manchán:

He had all the appearance of eternal youth about him. He was a man upon whom it seemed no stress or angst or sorrow or regret could find rest. He was constantly bursting with the enthusiasm of a child, eager to tell the adult world about all the things he was passionate about. He was ever impassioned, effusive; even glowing.

I hope that anyone who encounters Manchán’s words will appreciate the magic to be found in his books and recorded performances. Believing, though, that Manchán himself was the magical entity, a presence that others can admire but not emulate, misses the main point he would have made. Manchán did not actually make the magic any more than I made the white parrot. The magic was actually there all along. In the case of the Irish language, it waited centuries for someone like Manchán to bring it to light for the rest of us to learn from.

There is, to state the obvious, a whole lot of loss all around us right now. The potential loss of democracy in the country, loss of traditions we have long counted on, loss of a sense of security. Many of us are feeling a deep sense of loss following the killing of Renee Nicole Good, the 37-year-old poet and mother of three who was shot by an ICE officer in Minneapolis last Wednesday. Professor Kent Wascom, who taught Good at Old Dominion in 2019, told the New York Times: “What I saw in her work was a writer that was trying to illuminate the lives of others. I very much remember her being someone who made others feel better in that moment.” In a similar way, Manchán always seemed to manage a more positive approach. As he would say, “I see a world where people realise they have more in common than ever divided them.”

Manchán was also adept at identifying magic in others, maybe because he was so skilled at noticing the subtle nuances of the natural world. After hearing Liam Ó Maonlaí’s story of childhood struggle and loss, Manchán quickly transformed it into a tale of magic. Ó Maonlaí shares that Manchán’s response, “Oh, so you had to fly at a young age,” made him “look at life with a critical eye. In other words: to learn to fly.” I had a similarly lovely experience after I sent Manchán a link to an essay I wrote about appreciation that references his amazing work. He wrote me back:

A beautiful exploration of an Fóidín Meara and … a gorgeous parallel between Ireland’s reliance on myth as much as history, and Zingerman’s ability to bridge both conventional business practises and the almost magical realistic elements of visioning and believing strongly in a win-win, people-focused mode of business.

This ability to identify the magic and also to make it is, I believe, a trait common among those who’ve engaged with what Manchán calls the “other world.” It’s also what Carol Sanford taught me to see as Deep Understanding. People who arrive at Deep Understanding, like Manchán, seem strikingly different to those who encounter them. Their energy is ethereal, upbeat, lighter, livelier. Their insight and their ability to communicate it to others appear exceptional. The truth is, while these folks all live in the same world as the rest of us, they somehow see more, share more, and enlighten others in amazing ways.

The main message of this whole piece is that the magic that Manchán Magan, Lou Reed, Carol Sanford, and others we know manifest is something we can all make happen. The magic is there, waiting for us to learn how to work with it.

To confirm the point, I reached out to someone who is an expert in magic. Acar (AH-jar) Altinsel, a longtime and loyal Zingerman’s customer and the humble and the wise founder of Penguin Magic, has turned his own Deep Understanding of the magician’s art into the country’s most popular mail-order purveyor of magic-trick supplies. Seth Godin is a big fan, and so are many thousands of others around the country. “Can anyone make magic?” I asked Acar over email last week. “Yes,” he answered almost immediately. “Definitely anyone.” Which means to me that the white parrots of the world are almost always present, or at least about to appear. We just need to pay more attention. In a way, perhaps the subtitle Listen to the Land Speak says it all: We can take “A journey into the wisdom of what lies beneath us.”

While loss is in the air right now, there is still, per Lou Reed’s song lyrics and Manchán’s sense of the world, a lot of magic to be found all around us. Last week, I was fortunate enough to see a photocopy of a letter a local 10-year-old boy wrote to his cousin. This was not just an ordinary message from one young cousin to another who’s a year or two older and struggling, as so many are in the world today. This wonderful kid told his cousin how much she matters and how much he loves her in such a lovely way. I had tears in my eyes the whole time I was reading his letter. When 10-year-olds can write letters like that, then I know for sure that, regardless of what you might find in the financial pages of the Wall Street Journal, magic really does exist in the world. The problem is that most people miss it.

You don’t, I’m pretty sure, get to the sort of Deep Understanding Manchán had about the Irish language or Lou Reed had about pain, loss, rejection, and life on the edge by following society’s suggested life plans. Patti Smith shares in her new autobiography, Bread of Angels, that as a young child she was regularly “scolded for straying.” In truth, people need to stray from the straight and all too narrow to dig into something that could evolve into the exceptional. Straying seems to be a prerequisite for Deep Understanding. Manchán would regularly say that when he reached his late teens, fear of being forced into some kind of mainstream office job was part of what made him flee for the Far East, where he took up filmmaking and travel reporting! A few years later, Manchán was back in Ireland studying the ancient roots of his own culture, as he had studied so many others in his travels.

The Irish language, and many parts of Irish culture that Manchán studied so deeply, were banned in centuries past by British colonial rulers, much as Native American language and culture were treated here in the U.S. Manchán spoke and wrote regularly about “the indigeneity of Irish culture,” and the insight to be gleaned from it. The magic of Manchán, I would suggest, emerges from his Deep Understanding of the Irish language and his efforts to bring its nuanced detail and depth back into everyday awareness. As Manchán said so often, “Our people have always known that there’s only a very, very thin veil between us and the Netherworld…but to encounter it… It’s just beyond us, just between, just above and beyond the threshold, but it’s near to us.” And this is, indeed, the lesson I’ve taken from reading so much of his efforts!

Drawing on Carol Sanford’s good work, I’ve distilled four characteristics that make Deep Understanding practical and usable for nearly any subject:

- It emerges within an area of knowledge that already exists.

- It reframes that knowledge in new ways, creating new insights and ways of being in the world.

- It positively impacts the lives of others who are connected to the person doing the understanding.

- It helps the understanders become themselves in more meaningful ways.

In my view, this is very clearly what Manchán did with his deep studies of Irish. And it’s with Manchán (and Lou Reed) in mind that I’m now inclined to offer a fifth characteristic: What comes out of Deep Understanding, regardless of who has it or what it’s about, tends to feel like magic.

Magic, I realized last week, could well be an entrée into helping us understand our approach to what others experience as the hard-edged world of business. I’ve often tried to explain to people over the years that the truth of my work life is that I never started a business because I thought it would make me a lot of money. I know that may sound odd to many. Don’t get me wrong. I definitely didn’t want to start a business to lose money. Nor am I down on money per se. I have certainly made some over the years, which makes it possible for me to live with a lot less financial stress than most. It has never, though, been my motivator.

“Why else, then, would you start a business?” many wonder. I try to explain that for me, it’s mostly about making a great business. I’m more like Lou Reed, who, when asked many years ago if he was bothered by the Velvet Underground’s lack of commercial success, said, “We just wanted to make great music. The other stuff would have been nice, but we would never have changed the music to do it.” Same story here. This past weekend, it struck me that I might make better headway if I told them my intent was to make magic. What, I began to wonder then, if instead of the standard business Profit and Loss statements, we might publish regular Magic and Loss statements. The more magic we make, the better we’re doing!

Magic, well done and well managed, can, in fact, make you money. More importantly, it makes for a meaningful life. It means doing work we believe in, that we’re learning from, that others are leaning into, that is slowly but surely changing lives for the better. Money alone may sound great, but ultimately it all too often seems to send people in the wrong direction. As Seth Godin says, “People are measuring the wrong thing. Scale isn’t the point. Magic is the point. You want to find the right scale that lets you make the magic you want.”

The authors of the other day’s New York Times op-ed point out that when people dig deep and really pay close attention over a long period of time, the results often appear to you and me as magic. Attention, I see now, opens the door to Deep Understanding, which many later understand as magic. Whatever we call it, it is very clear that it reveals new and wonderful things, things that have been there all along, but that far too many people have chosen not to look at long enough to see. Here’s an excerpt from their “Twelve Theses on Attention”:

I. The astonishing reality of things and persons—this is the object of pure attention.

II. True attention does the work of bringing forth. It is the aperture through which the latency of things and persons becomes present. … unmixed attention—pure attention to what cannot be used, to what no one already wants, to what promises no knowledge or gain—does not require doors, because it walks through walls.

III. This true attention, given to objects, unerringly reveals the presence of others.

. . .

What is needed is an ethics of attention. This is akin to a practical mysticism. Practical mysticism is not impractical. It is no more and no less than the effort to draw closer to the astonishing reality of things, through those forms of pure attention that are unmixed with evaluations of utility and judgment, and free from the deforming grasp of a seizing hand (or eye or mind).

So what do we do to make this kind of magic happen? While I’m not totally sure, I know that you have to start somewhere. As Seth Godin’s voice in the huddle in my head reminds me regularly, “It’s better to ship imperfect work and build on it than it is to push pause and wait for near perfection.” I’ll share something of a start here. With Manchán, Acar Altinsel, Carol Sanford, and Seth Godin all in my mind, here are six steps to making magic. Or six steps to developing Deep Understanding. Or, maybe better still, a recipe for entering into a world where Irish fairy stories and white parrot sightings are an everyday occurrence:

- Pay more attention. Manchán, obviously, did not invent Irish, and Lou Reed definitely didn’t develop loss, rejection, and social “outcastism.” The material for the magic is there. We just have to embrace it, uncomfortable as that may be. There are, after all, metaphorical white parrots, real-life Manchán Magans, and caring 10-year-old cousins all around us, waiting for us to tune in.

- Go back and attend again. Instead of scrolling to the next item, stay with the image. Study regeneratively. Go deeper. And deeper. And deeper still. When you think you’ve done all you can, go back and find ways to do more again, still. Repeat regularly. You’re at the beginning still, but at least you’re going in a good direction.

- Connect things. There is much more about this in Secret #39. But yes, connecting things that are not otherwise connected can often make magic. Connect what’s in your head with what’s in your heart, or what’s in the news with what’s new that you’re learning. Manchán brought ancient Irish words into modern conversation by writing about them and speaking about them so regularly and so beautifully. Lou Reed connected pain, rejection, and emotional crisis on the street with popular music.

- Put it all into new frames. Take what you find and frame it, fit it, or refit it into your own world. Shape it to your own sensibility while letting your sensibility be shaped by it. As Manchán would say about the start of his deep work with Irish, “I decided I want to take back the Irish language and my connection with my surroundings, but not have it be about violence.”

- Sort out how to share it. Figure out how to take this magic that you are assembling in the secrecy of your own mental spaces into the wider world.

- Practice in public. Put it out there regularly because, as Acar Altinsel says, when it comes to magic, practice really matters. You can’t make magic by simply sitting at home and not sharing what you’re imagining with others. As Seth Godin reminds everyone who will listen, we have to ship good work. He adds this:It’s not complicated, but it’s surprising.

The work makes us who we are.

…

Do the work, ship the work, now you’re creative.

Not the other way around.

Don’t wait for it to be perfect.

Don’t wait to be inspired.

And don’t wait for someone to give you a badge or a diploma or a label.

Simply do the work.

Ship the work.

Repeat.

…

We do the work and then we become creative.

My message, then, is that as magical as Manchán, Lou Reed, Acar Altinsel, Carol Sanford, and Seth Godin can seem to the rest of us, there’s nothing they have done that you and I aren’t able to make a personalized, unique-to-you-and-me version of ourselves. In “Manchán and Otherworld,” a performance that Manchán did for and with the filmmaker-musician Myles O’Reilly (also a magic maker) three years ago and then released online half a year later, he spoke of insight from the Irish classic Tir Na Nog:

It seems that all these accounts are trying to tell us that it’s not the simplest thing to get there despite the fact that it’s everywhere. But the challenges of getting there are worth overcoming.

Manchán’s words are a summation of why we would want to let go of the road more traveled, the ordinary, mainstream jobs that Manchán and I both managed to avoid, and instead tap into the magic. As Manchán says, this idea of magic “makes no sense, no logical reason sense in a world that’s based on the clock on time and space foreign.” Many withdraw when they encounter a bit of magic, quickly returning to the safety of the straight and narrow. As Manchán points out, though, it might be too late to escape what the magic offers: “Part of you was in the other world from the moment you first thought about going there from the moment you decided to go there you were there.”

Manchán’s presence is already sorely missed by many, many people, but his magic continues on apace. Asked in an interview whether the passing on of his poetic ancestors, Aogán O Rathaille and his great grand-uncle, The O’Rahilly (or Mícheál Seosamh Ó Rathaille, his full Irish name), meant that their work was lost to the world, Manchán answered quickly and confidently: “They aren’t lost. I feel like they remain alive through their writing.” This is, of course, also true of Manchán. The magic and the loss move forward together.

In a world where both magic and loss are always present, interwoven, intertwined, and overlaid, it becomes increasingly important that more and more of us work hard to make magic, that we don’t let the losses get us down. The magic, as Manchán would remind us, is always there, somewhere near the surface. Our role is to dig in, to study hard, to immerse ourselves in learning, and then to be ready to receive whatever magic appears. If we’re patient and persistent, positive, and perceptive, sooner or later it will come. White parrots, ancient Irish words, and an array of old Lou Reed songs are all waiting for us to find them and put them to work. As Lou Reed invited all of us to do so many years ago, we can all “Take a walk on the wild side.”

One thing I’m now certain of is that when we’re looking in the right direction and approaching things like Manchán did—working hard, refusing to give up, and reflecting regularly and deeply—magic surely awaits us. And as Acar Altinsel makes clear, “Anyone can do it!”

Delve into Deep Understanding

P.S. Speaking of magic and Irish writers, on March 25th and 26th, I will be co-teaching with my good friend Gareth Higgins! Gareth is the author of the amazing How Not to Be Afraid and also The Seventh Story (co-written with Brian McLaren). It will be the third straight year we’re doing this special two-day ZingTrain seminar, “Reframing Your Leadership Stories & Beliefs.” This is a chance to learn from Gareth’s great work on the power of storytelling in our lives and blend it with deep work on beliefs, the kind I detailed extensively in The Power of Beliefs in Business. Both Gareth and I speak and teach regularly around the world, but this is the only time we do it together. And, said humbly, it is a magical experience. Spaces are limited. Hope to see you there.

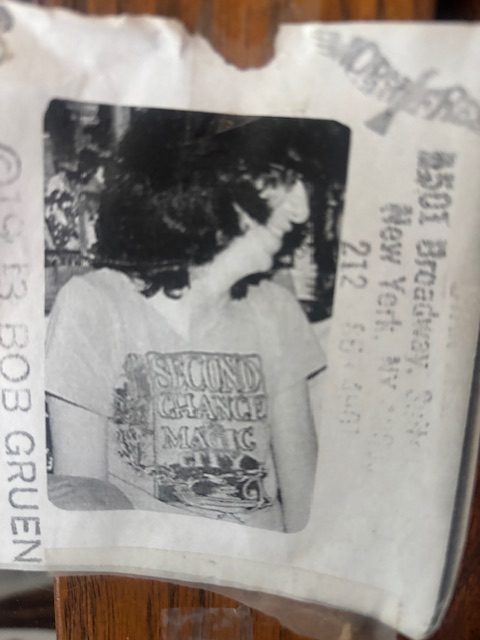

P.P.S. As if by magic, while I was working on this piece, I heard from John Carver, who started the Second Chance venue in Ann Arbor in 1974. I wrote about him a few weeks ago in the essay that started with the Ramones playing in Ann Arbor in the first week of October 1981. In the photo, Joey Ramone is wearing a t-shirt that says “Second Chance, Magic City.”