Unexpected, Upbeat Notes from the Huddle in My Head

Why I wish I’d known Joey Ramone and other imaginative oddities

On the rather foggy, drizzly, and gray afternoon of Monday, October 5, 1981, the Ramones were signing album covers at Schoolkids Records, the classic Ann Arbor shop that inspired the name of the #38 sandwich at the Deli. The band’s latest LP, Pleasant Dreams, had just been released in the third week of July, so the four musicians were actively touring, as they often did throughout their 32 years together. There are some great black-and-white photos of the signing, shot by Robert Chase, who I happened to see at the Coffee Company this past Sunday!

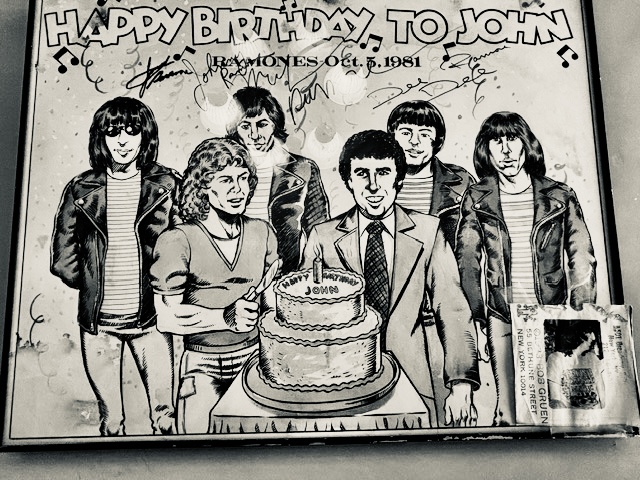

Later that evening, the band played at the Second Chance on Liberty Street, just up the block from Schoolkids. Tickets were $9.50, and the show was scheduled to start at half past nine. It was the Ramones’ fifth Ann Arbor appearance. They’d played the Second Chance regularly ever since their first record debuted in 1976. For that first show, in late March of 1977, they opened for Fred “Sonic” Smith’s Rendezvous Band. John Carver, Second Chance owner and a regular at the Roadhouse all these years later, reported that the Ramones requested $400 and a bag of cheeseburgers as their fee. The photo above is a drawing the Ramones made for John, done for his October 5 birthday at the time of the 1981 show.

Writing in The Michigan Daily the day of that first Ann Arbor gig in 1977, David Keeps called the Ramones a “New York-based, Benzedrine-powered powderkeg.” The week after the show, Keeps authored a wonderful review, calling the band “Undeniably the loudest, fastest band around.” And 25 years later, Elizabeth Hill wrote another Michigan Daily story about the band. She noted that they used a simple formula: “Four chords, four guys, same last name and no song over two minutes.” It was uncomplicated, but no one else had ever done it. And although it may sound easy, in practice, playing that way was anything but.

I didn’t attend the show that October evening, but I already owned all of the Ramones’ first four albums and had spun them on my turntable at home many hundreds of times. While the band was high on my listening list, I had other issues on my mind that month. I hadn’t said anything about it to more than a handful of people, but I’d spent the summer and early autumn of 1981 considering whether or not I ought to leave my job as a kitchen manager at Maude’s. The work, pay, and people were perfectly fine, so there was really nothing wrong with it, and I’d been with their organization for almost four years. Over time, though, the work had begun to feel less and less inspiring. I was totally into food and cooking, but I had a growing sense that where the organization was headed, though it was a well-accepted and oft-followed path for mainstream business growth, was not a place in which I wanted to spend my life. Quite simply, the work was not the soul-filling type that I intuitively, if still kind of subconsciously, knew I wanted.

Three weeks later, on November 1, 1981, perhaps in an unconscious acknowledgement of the Ramones’ punk spirit, I gave two months’ notice at Maude’s. I was completely unclear on what I would do next. Two days later, Paul Saginaw, then my friend and soon my business partner as well, called me: The little two-story brick building across the street from his existing business, Monahan’s Seafood Market (co-owned with Mike Monahan), was going to be available. Paul and I had worked together in the restaurant a few years earlier, and he thought the two of us should go check out the space. The time seemed right, he said, to open the deli we had talked about off and on over the nearly four years that we had known each other. Less than five months later, on March 15, 1982, we opened Zingerman’s Deli. It was the culinary equivalent of starting our own band. Given our very small opening budget and down-to-earth approach, we did it in a pretty punk way. I didn’t realize that at the time, but thanks to this reflection on the Ramones, I do now. As Kirk Hammett of Metallica later said of Joey Ramone: “He ignored all the trends. He didn’t follow anything. He set his own trend.” We were always intent on doing it our own way, and we still are today.

Over the last couple of weeks, I’ve found myself wishing that I’d known Joey Ramone. Not because he was a rock ’n’ roll star or because I loved the band’s music—that’s what would have drawn me to Schoolkids to get a signature back in 1981. Today, it’s still fun to listen to the music and watch clips of the band playing live. I like to see Joey’s one-of-a-kind stage presence in action. Elizabeth Hill, writing in The Michigan Daily 25 years ago this spring, described 6-foot-6-inch Joey as towering over everyone else, “staring behind his trademark shades and black curtains of hair” as he “belted out countless punk songs at a breakneck pace, sometimes ballistic, sometimes bubble-gum.”

All that said, my interest now is centered much more on Joey Ramone’s philosophical and artistic inspirations, his emotional intelligence, his joy and generosity of spirit, and his intellectual insight. I have a feeling that if I had known Joey Ramone in 1981, he’d have told me to quit my corporate job long before I had the courage to do it. I also think he’d have encouraged me to find something much more aligned with what the Ramones were all about—being themselves in unique and wonderful ways. As Joey used to say:

To me, punk is about being an individual and going against the grain and standing up and saying, “This is who I am.”

Earlier that year, in July of 1981, by coincidence (or maybe not), the Ramones released a song called “This Business is Killing Me.” I can only smile now as I think back on it. I wasn’t yet in a mental place where I was consciously looking for song lyrics to inform my life, nor was I self-aware enough to notice that I was doing work that was fine but not hugely fulfilling or as fun as it once had been. Fortunately, I gave notice that fall anyway. Paul called, we quickly concurred, and after about four months of renovation and preparation, we opened. For many years now, I’ve been fortunate to be in a business that enlivens me and is pretty darned true to who I am.

Fast-forward 44 years to late in the fall of 2025. It was a few days after publishing a piece about the amaZingness of the Zingerman’s Community of Businesses (or the ZCoB in what we call Zinglish) huddle. I had sort of a strange thought.

As those who know me well are well aware, odd-sounding ideas are not uncommon for me. Some sound good when I think of them, but I quickly let them go after further reflection. This one, though, I really liked. Strange as it sounded when I first said the words out loud, it still seemed to make sense as I thought about it more. Not surprisingly, though, within a day or so, a couple of critical voices began to kick up in the back corner of my mind, telling me to forget the whole thing. They dismissively implied that I was wasting my time and that the idea at hand—or, more accurately, in my head—was way too wacky to be writing about, let alone acting on.

For a few days, I listened to those negative voices, setting the idea aside while I engaged with the myriad other things I have on my mind. Still, though, the idea continued to resonate. Fortunately, those critical voices that have been with me for most of my life are not the only ones I have in my head. Now, 44 years and a few months after the Ramones played that gig here in 1981, I have a whole host of positive voices that come into my internal conversation to get it back on track.

One of them is Hugh MacLeod, the Scottish author of the highly recommended Ignore Everybody. I’ve never met Mr. MacLeod in person, but I’ve read—and then reread half a dozen times—his book, underlined it extensively, and internalized much of his inspiring and insightful message over the years. MacLeod has much wisdom to impart, including this lovely line that I know now to be both accurate and super helpful: “Good ideas are always initially resisted.”

To wit, when the Ramones played their first shows together, they were almost universally panned by the music press. They were often described as “aliens.” Per MacLeod’s insight, though, the critics turned out to be totally wrong. The band’s 14th and final album, Adios Amigos, was released 30 years ago this past summer, and they were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2002.

For years, I took MacLeod’s words to mean that when I introduce a new idea into the organization, there will always be resistance, and that I should not let the resistance keep me from advancing something that I believe to be true in my gut. Last week, though, I had what Stas’ Kazmierski—former ZingTrain co-managing partner, the man who taught us visioning and bottom-line change, and someone whose voice I’ve internalized—taught me to call a “belated glimpse of the obvious.” The resistance to good ideas that MacLeod is writing about is not restricted to what others have to say about our suppositions. The same sort of resistance happens inside our own heads, too.

MacLeod’s wise words are always helpful! And happily, he is not alone in his encouragement. Stephen Pressfield’s voice has become fairly well ensconced in my head over the years as well. As he wrote in his terrific book The War of Art:

Resistance really takes the shape, for me, in voices in my head telling me why I can’t do something or why I should put it off for another day, procrastinate for another day.

…

Resistance is experienced as fear. … [T]he more fear we feel about a specific enterprise, the more certain we can be that that enterprise is important to us and to the growth of our soul.

In this case, having learned what I’ve learned over the years, I can let my critical voices speak their minds negatively but not give in to what they are calling for. MacLeod and Pressfield, I’m happy to say, won the metaphorical day.

So, pray tell, what’s the odd insight? In the Ramones’ world, putting forth this insight could be considered the release date—the first sharing of something new with the world, or my world at least. It’s not as exciting as the first Ramones record back in 1976, but this new idea has had my mind abuzz. It’s the realization that, much like we have our regular huddles at Zingerman’s, including the big ZCoB huddle I’ve written about recently, I have a huddle going on in my head. No one else can see it, but I know now that’s in there.

As with the ZCoB huddle, the quality of the huddle in my head is determined by:

- Which voices are present, which ones speak up, and which ones are heard

- How well the gathering is facilitated by me (or you, if it’s your huddle)

How effectively that internal huddle runs makes an enormous difference in how well I lead. This is also true for the relationship between the ZCoB huddle and our organizational health. Meeting quality, quite simply, matters more than most people realize.

Singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen (whose 1977 album Death of a Ladies’ Man was produced by Phil Spector, who later produced the Ramones’ 1980 release, End of the Century) once said, “The voices in my head, they don’t care what I do, they just want to argue the matter through and through.” That sounds a lot like how I spent the first 30 years or so of my life. Lots of voices, lots of chatter, very often not very constructive, all having at it in my head and all talking at pretty much the same time. In hindsight, I’ve realized that when I experienced hard times, mental chaos, anxiety and confusion would always follow. Knowing what I know now, the sound inside my mind must have been something akin to listening to five separate Ramones songs simultaneously. The volume and pace are high, but very little constructive material comes out in the chaos and confusion.

By contrast, if we learn to manage the voices in our heads well and get the right voices in the room, the whole thing can be a much more productive experience. An experience that, when it’s working well, is akin to the kind of beauty, insight, dignity, grace, and collaboration that I witnessed in the ZCoB huddle a few weeks back and then wrote about afterward.

Why would all of this matter? Because, quite simply, the quality of the conversation in our heads is manifested in the quality of everything else we say, decide, and do in our lives. As I wrote in Secret #38, “Thinking About Thinking,” the way we think is, often unconsciously, the way we work! And the more positive and insightful voices we have in our heads, well, I’m pretty sure the more positive and insightful our work is going to be.

While I’ve loved the Ramones’ music for many years now, I knew next to nothing about Joey Ramone other than he was very tall, cool, and a one-of-a-kind punk rocker. The last few weeks have changed that. Having spent some time getting into his life story and worldview, I’m absolutely going to invite him to my internal huddle. Joey Ramone had the sort of ethical voice I prefer to surround myself with. As he explained, what drove him was punk: “I want to be my individual self. Doing it your way. Your own principles. You’re going against the rules, so a lot of people may turn on you.” Joey Ramone demonstrated that you can live in ways that are aligned with your values anyway. As he said later in his career, “We always stayed true to what the Ramones are.” I certainly hope that that’s what folks will one day say about what we do at Zingerman’s!

Joey Ramone, born Jeffrey Hyman in 1951, grew up in a middle-class Jewish family in Forest Hills, New York. He was diagnosed with OCD early on. In those days, there was very little good support, and he struggled with deep insecurity. His mother would later say, “He was quiet and shy. He wasn’t like other kids. He was a loner. The projections for him were not good. He was a slow student. But he was highly intelligent.” A young Jeffrey was apparently quite geeky, always super tall and skinny, and was regularly pushed around by the tough kids in his high school. Fortunately for us, the “highly intelligent” won out over the other issues, and the kid who would later become Joey Ramone persevered. He started playing drums at 13, and he was a big fan of the Stooges, David Bowie, The Who (in 1994, the Ramones recorded a cover of “Substitute”), and many other artists. In 1972, he became the singer in a glam-rock band called Sniper. And then, in 1974, he co-founded the band that famously became the Ramones. Soon Jeffrey Hyman became Joey Ramone.

In the spring of 1976, the band released their first album, The Ramones. I bought a copy, almost certainly at Schoolkids, shortly thereafter. It was—and still is—awesome. At the time, I just liked the music. I didn’t understand contextually or intellectually exactly what the Ramones were doing with music and why it was so hard to pull off—all downstrokes, barely ever taking a break between songs, playing and singing faster than anyone else around.

The Ramones were definitely far more than just another band. According to Andy Schwartz, former editor of New York Rocker, “They were the great Johnny Appleseed pioneers of punk rock.” Lou Reed, yet another Jewish New York punk rocker, was cajoled by friend and manager Danny Fields into coming to CBGB to see the Ramones play in 1975. Reed loved them, as some footage from the documentary Danny Says makes clear. Per his style, he didn’t mince words:

They’re crazy. That is without a doubt, the most fantastic thing you’ve ever played for me, bar none. It makes everybody else look so bullshit and wimpy—Patti Smith and me included, just wow. Everybody else looks like they’re really old-fashioned. That’s rock ’n’ roll. They really hit where it hurts. They are everything everybody worried about; every parent would freeze in their tracks if they heard this stuff.

John Holmstrom, artist and co-founder of Punk magazine, went to see the band back in one of their shows at CBGB in New York in the mid-’70s, saying later that “The Ramones defined punk rock. … They were the first punk rock band. That first album changed the world.” The Ramones went on to have a huge influence on The Clash, the Sex Pistols, and a host of other bands. Bono of U2 would later say, “We would not be here if it weren’t for the Ramones.” And that’s not to mention the millions of anxious young people struggling to find their footing, as Jeffrey Hyman did back in Forest Hills in the ’50s and ’60s, who’ve found something they need in the Ramones’ music, too.

While the band gained fame and acclaim, Joey Ramone, I’ve come to realize, was far from being just another rock star. His worldview, his philosophy, and his positive and supportive nature set him apart. In the Ramones documentary End of the Century, Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore says:

He was to thousands, hundreds of thousands, millions of people a liberator. He liberated them from their own sense of failure, unpopularity. Joey was a hero because he overcame the odds. He triumphed over geekiness. And he started off as an alien in the world in which he was raised. Joey was never the healthiest person in the world, but he was one of the strongest people I’ve ever known, you know, and he managed to fight off anything and everything all the time.

As you can tell, Joey Ramone refused to conform to social norms and instead found ways to create a life of his own, to live his vocation, and then to share his work in constructive and creative ways that inspired young people like me, people who wanted to push back against the status quo. I love that he did it his way. Longtime rock journalist Legs McNeil wrote:

You know, Joey took everything that was wrong with him and made it beautiful, which I always thought was the greatest thing about Joey, and … the whole philosophy of punk. You take everything that’s shit and you celebrate it and make it good.

McNeil’s counterpart, Bill Bois, writing in TNOCS a couple of months ago, described Joey beautifully:

His depth made him attractive, even fascinating.

His lanky physique and goofy movements made his sudden intensity seem raw, real, and unrehearsed, because it was. His authenticity came across as courageous.

…

He could be tough without being mean, and tender without being weak.

…

Joey didn’t try to be other people’s idea of the ideal singer.

He owned his oddness and made it part of his art. Refusing to hide one’s weaknesses takes confidence, and confidence is deeply attractive.

Having reflected further on his own article, Bois embellished his original piece with additional comments about Joey Ramone, comments that really drove home how special a person Joey seemed to be.

[Joey] wrote what he wanted to write and sang the way he sang without worrying about what people thought. That’s what artists should do.

Say what you need to say. Express yourself the way you want. No one else can do that, only you. Some people will like it, others won’t, but that’s not your concern.

…

That’s what made Joey cool. He didn’t care whether you thought he was cool or not. He just was.

That is, no question, the kind of person I’d want in my huddle. I figure that my figurative Joey Ramone would be super supportive, especially of seemingly oddball ideas like this notion of having a huddle in my head. Unlike the constantly self-critical voice I had in my head as a kid, Joey Ramone’s voice seems joyful and positive. In a piece published in Far Out in London last weekend, Lucy Harbron wrote of the Ramones:

If the band liked you … they’d back you hard and back you loyally,

Like Joey Ramone, I spent many years working to locate my own voice in the (dis)array of critical voices that made it incredibly hard to hear the more positive voices that I knew were also in there, just quieter. So much chatter. So little clarity. Way too much overthinking and self-doubt. You might be able to relate.

Today, it’s a totally different story. Critical voices continue to appear, but there are only two or three of them compared to many dozens of much more positive ones that now show up in my mind so regularly. It’s quite a list, really: Paul Saginaw. Peter Block. Emma Goldman. Seth Godin. Philosopher and later friend Sam Keen. Brenda Ueland, who I wrote about last week. Amazing authors like Julia Cameron and Anne Lamott. Peter Koestenbaum. Rebecca Solnit. Grace Lee Boggs. Gustav Landauer. Maggie Bayless from ZingTrain. Good friends like Molly Stevens and Melvin Parson. John Abrams. I could go for ages and pages, but you get the idea. Some are folks I’ve known in person for many years. Others, like Joey Ramone, I’ve never actually met. Either way, their voices are in the huddle in my head. And with fairly effective facilitation, I’m able to assimilate a wide range of perspectives from people whose views I value a great deal, all of which inform what I do. Decisions are still mine to make, but those decisions are so much sounder thanks to all the good input from a pretty prestigious and values-aligned group of huddle participants.

The cool thing about the huddle in your head—I’m assuming you have one, too, though I know you also may not—is that, unlike real-life huddles or any other meetings we have, we can add anyone we want to it. As long as the participants aren’t perpetually talking over each other and trying to take over the room, the more the merrier, right? So if we come across someone whose wisdom we wish we could tap into regularly, we can slowly but surely and effectively add their voice to our internal huddle.

To do that, we simply need to spend a lot of time with them. That can be in person, as it has been with Paul Saginaw. It can be reading their written work, as it was for me with Emma Goldman. By listening to their talks online. Or a combination of all of those, as it’s been with Peter Block. I’ve read all of his books, I’ve listened to him online, and we talk in person. Essentially, we can get to know new participants in the internal huddle through the sort of regenerative study I wrote about a few weeks ago. When I take a deep dive into the work of someone who inspires me, my energy will almost always increase significantly. Which, as you can tell, is what’s happened to me recently with Joey Ramone.

It turns out that the idea of a huddle in your head isn’t quite as unusual as my critical voices would have had me believe! As Rochel Spangenthal wrote in a 2015 Hevria magazine essay entitled “How To Train The Voices in Your Head,” “It is not just the crazier amongst us; we all hear voices in our heads.” In “Getting to Know the Voices in Your Head,” a 10-year-old Scientific American piece, journalist Ferris Jabr wrote that “We talk to ourselves to stay motivated, tame unruly emotions, plan for the future and even maintain a sense of self.” All of which is, of course, just what happened for me in the ZCoB huddle a few weeks ago.

The original research that introduced the idea of inner voices was done many years ago by another middle-class Jewish guy. In 1977, the Ramones released Rocket to Russia. But half a century earlier, Lev Semyonovich Vygotsky, a Russian and Soviet psychologist studying child development, suggested that we’ve all internalized the voices of others, at first primarily our parents but also others of influence. In fact, this single line from Vygotsky sums up this whole essay in five words: “Through others we become ourselves.” A hundred years ago this month, near the end of 1925, Vygotsky completed his graduate dissertation, “The Psychology of Art.” Soviet censors kept it from being published until the 1960s. In it, he wrote that “art is the collectivisation of feeling,” a beautiful description of both the music the Ramones made together and of what we do here in the ZCoB!

Ethan Kross, a psychologist at the University of Michigan, wrote Chatter, a nationally recognized book that goes deep into the impact of inner dialogue. I happened to meet him last month when he was having dinner at the Roadhouse. Kross writes, “The inner voice is a kind of Swiss army knife of a human mind. It is a multipurpose tool that lets you do many things.” I prefer “huddle” to “knife” since I imagine the inner voices as being present in varied abundance. I also imagine myself facilitating their input effectively to get to good conclusions. The idea, though, is similar. As Kross writes, “The mind is flexible, if we know how to bend it.” For me at least, one of the best ways to do that is to add new voices to my inner huddle! Each new voice adds more diversity and depth. Kross, in what could have been an unconscious nod to Vygotsky, says that “We are like Russian nesting dolls of mental conversations.” This week, I’m welcoming Joey Ramone into my Russian history major’s mind.

To be clear, it’s not a bad thing to have some critical voices in our internal huddles. They raise what could be appropriate concerns and bring a touch of cynicism or skepticism. As management consultant Tony Fakhry writes, “It is unwise to get rid of negative thoughts because they can serve a purpose. … All thoughts have their place in the mind, even negative ones. … By turning down the volume on negative chatter, you allow the authentic self to emerge.”

Many albums, thousands of concerts, and plenty of ups and downs later, Joey Ramone died, sadly, in the spring of 2001 from lymphoma. He passed away a few days short of the 25th anniversary of the release of that first Ramones record and a month before what would have been his 50th birthday. As Bill Bois wrote about him:

Emotional closeness—the sense that someone is letting you into their private world — is rare in Pop music, let alone in Punk.

But he had it.

If this internal huddle idea isn’t too terribly strange for you, try giving it a bit of thought. Here are a few questions to mull over:

- Who’s in the huddle in your head right now?

- How can you better facilitate the various participants contributing to your inner conversation, letting the negative voices have their say but keeping them from dominating?

- Who would you like to add to your huddle? Who can help you to add ever more meaning? Who can support you in living a life like Joey Ramone’s—not to be a rock star, but rather to live in a way that makes you say with calm and centered confidence, “This is who I am”?

Let me know what you learn!

Wisdom, emotional intelligence, a deep determination to be himself, exceptional creative expression, joy, and generosity … the things Joey Ramone brought the world make him the kind of human I’d like to have to the huddle in my head. As Joey said, “For me, punk is about real feelings. It’s not about, ‘Yeah, I am a punk and I’m angry.’ That’s a lot of crap. It’s about loving the things that really matter: passion, heart, and soul.”