The Inspiring Impact of Promises Beyond Ableness

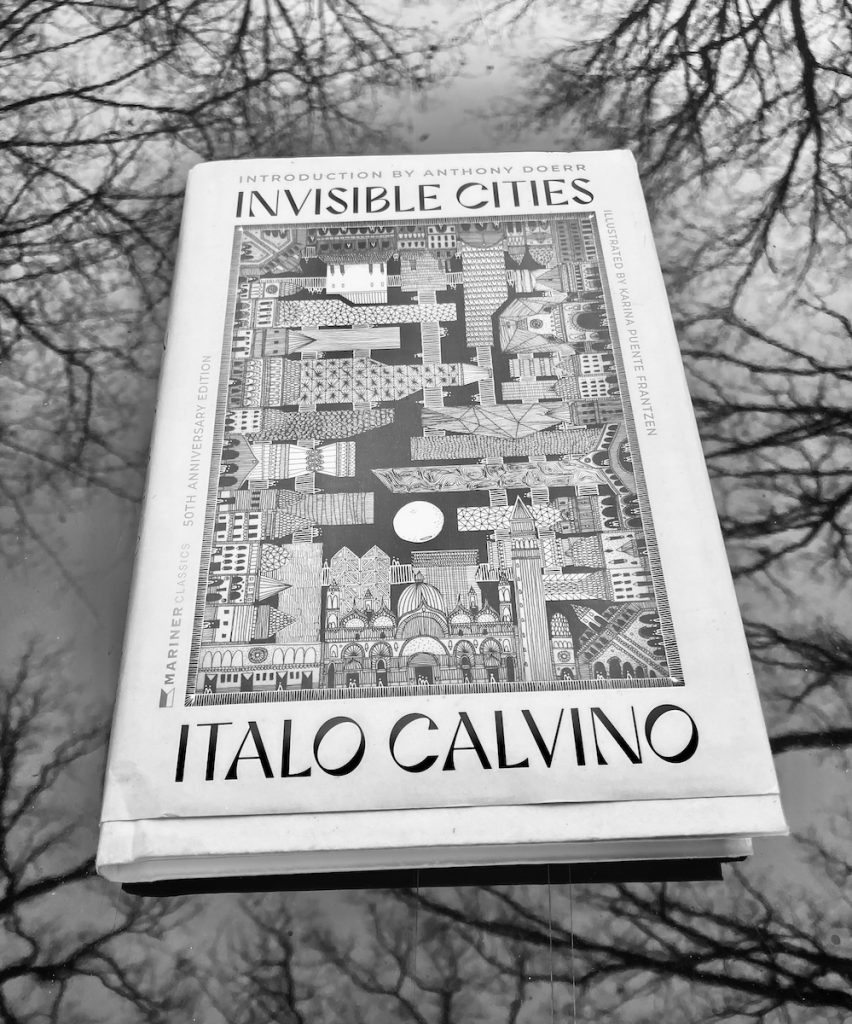

The insight of Italo Calvino and a path to more positive living

Ever committed yourself to something big, something you care deeply about, but that you’ve never done before? Something you believe in your heart you can become adept at, but that you have little idea how to do right now? Ever experienced that anxiety that arises when you start to tell other folks what you’ve decided to do? Does that foreboding fear of failure come flooding in when you declare your intentions to the people you care most about? That’s definitely what it feels like for me.

If the details of this situation sound familiar to you, then I say, “Awesome!” You’ve likely made what radical business writer Carol Sanford calls a “promise beyond ableness.” For the purposes of this piece, I’ll call these promises PBAs.

In the third week of November 1974, around the same time I’d started learning how to be a line cook, the novelist Joseph McElroy published a piece in The New York Times Review of Books about the newly released work of one of Italy’s best-known writers. Looking back at the article late last week, the first few lines caught my attention:

“Invisible Cities” is a new book by Italy’s most original storyteller, Italo Calvino. But this time not a book of stories. Something more.

“Something more” is indeed worthy of our attention. It’s also the particular subject of the essay that follows.

In the introduction to the 50th Anniversary Edition of Invisible Cities, author Anthony Doerr writes about his own imaginative and exploratory childhood, sharing how, as a young boy, he would regularly make up stories while playing with his older brothers:

We search for secret doors. … You find one.

I agree with the young Anthony Doerr who’s embedded so deeply in the adult author’s memory. A meaningful part of our life’s journey starts with just that sort of search. Given time, focus, good self-management, and hard work, all of us can—and, I believe, will—find a “secret door” that’s right for us. We just have to learn how to look for it.

In essence, the decision to go through that secret door is just the sort of PBA that Carol Sanford was so passionate about incorporating into people’s lives. When you take a deep breath and decide to go determinedly through that door, you commit to a PBA. When you share your decision with the world so others know about it and then dive in and start working at it, the odds are high that you will arrive at “something more” in time. When you put in the work, and things work out well, that “more” can be life-changing.

Invisible Cities, as I’ve come to view it, is Italo Calvino’s invitation to see what sort of secret doors might be out there and which ones are well-suited to the way we would like to live our lives. Not necessarily living in the narrow ways that mainstream society deems “successful,” but, rather, by imagining inspiring and enchanting possibilities. Calvino encourages us to explore, much as one of the book’s two main characters, Marco Polo, once explored the world.

Neither Calvino nor Polo, of course, used the term “promises beyond ableness,” but the possibilities PBAs present are essentially what I believe the book is all about. Alex Sager, a philosophy professor at Portland State University, writes that Calvino’s “tales of Marco Polo are exercises of imagination and of perception to alert us to reality and to help us imagine how things might be otherwise.”

In the fall of 2012, 40 years after Invisible Cities came out and a little over 800 years after the real life Marco Polo passed away in his hometown of Venice, Carol Sanford published an intriguing piece of her own. In a 21st-century business kind of way, she offered a path we can take to get to an uplifting future, a path that, with a lot of hard work and a bit of good fortune, can help us get to “Invisible Cities of our own creation.” Sanford explains:

The most fundamental managing principle for innovation is to believe in and practice the principle that everyone is growing and learning and is part of the innovation team.

That is why I created a work system for managing people that sees development as core and is based on “promises beyond ableness”—promises by people to do something that they know they can’t do now, so that they have to grow in order to succeed. Those who make promises beyond ableness have seen something that really needs to change. It is worth the climb, and they commit to the personal and professional growth to accomplish it.

A PBA, as Sanford has frames it, is an answer—a positive, inspiring, and very practical one—for any of us who feel stuck and those of us who are inspired to do more, to grow, to make more meaning in our lives and in the lives of those around us. PBAs can be huge in scale, like envisioning an amazing workplace we will create and how it might look 10 years into the future. Or they can be far smaller by the world’s standards but still significant to the person doing them and the people touched by them. In fact, I now realize that when I sit down to write this essay every week, I’m engaged in making a small-scale PBA come alive. I’m not just restating old information; I’m figuring things out while I write. It’s scary, for sure, but I’ve freely agreed to the deadlines that we have in place, and I’m dedicated to doing the work in a way that will benefit readers around the world, the people who make up the ZCoB (Zingerman’s Community of Businesses), and me in the process.

In a June 2013 piece in The Atlantic, Ilana Masad encouraged readers of Invisible Cities to savor its complexity: “Don’t let this volume’s slimness fool you into thinking it’s insubstantial. Calvino’s masterpiece has multiple layers of riddles.” Which is also, in a sense, the unnerving reality of Carol Sanford’s PBA construct. The future is unclear because, in great part, we are all currently working to create it. Our lives are layers of riddles, riddles that, like writing this essay every week, creating a business from scratch, or learning a new skill, we have the ability to answer. PBAs help make that sort of positive future a reality for anyone open to pursuing it.

When many people first learn about Sanford’s idea of promising beyond one’s ability, they get stuck worrying and wondering just what it is, exactly, that they should promise. Best I can tell, the answer is “I don’t know, and neither does anyone else.” We have to sort it out for ourselves. Self-reflection and internally driven decision-making are important parts of the journey. As Ilana Masad writes, “Whether the places [in Invisible Cities] exist literally or only metaphorically … well, that’s up to you to decide.” While we can, of course, confer with others whose perspectives we care about, in the end, we each must choose the PBAs we are going to pursue for ourselves.

Writing in Medium in the spring of 2019, Carol Sanford noted that our growth as individuals is a natural outcome of the work that emerges from making a PBA:

It is often said, “people are resistant to change.” This is not the case when approaching change through a new and shared understanding of the true nature of change and the elements of change that typically trigger resistance. Developing this understanding and designing from that new mindset is the essence of this phase.

A key difference in this form of work design is to require everyone to make a “promise beyond ableness” which is to contribute something significant to a stakeholder outside the business. It is beyond the current ability of the person making the commitment, would clearly benefit the stakeholder as measured by their terms, and will grow the person making the promise to deliver. They become self-directed, as part of a team, delivering on this promise. It has the effect of awakening motivation, creating new capability for the organization for the future, and building a business that is owned by everyone.

When I give presentations about Zingerman’s life and leadership philosophies, frameworks, and approaches to business at public events, one of the most common questions people ask goes something like this:

This is all great stuff. I love it. It’s just that I work for a boss whose style is almost the exact opposite. What should I do?

The question comes, most typically, from middle managers and folks who are far down the org chart. They’ve often been led to believe they have no say in how things are run, so they feel like this is the truth. I remind them that they likely have more power and influence than they are imagining. Usually, meaningful change can—and does—come in far smaller increments than most have been taught to look for.

When I answer the question, I make clear that because I started Zingerman’s and have been in a leadership position ever since, it’s been ages since I was in the sort of spot they’re in. But with that caveat, I usually suggest pushing ahead anyway. We don’t need to wait for our bosses’ approval to get going in ways that make a difference. Most of us have the power to make small, positive changes in the way we lead and live, changes that will make a meaningful difference but won’t create problems for anyone. Starting to practice servant leadership or the six elements of dignity probably isn’t going to alienate anyone, but will, when we stick with it, make a meaningful difference. Every act of kindness, every new learning, every day we make dignity the heart of what we do … they all have a positive impact!

In a sense, I’m suggesting a small version of Richard Rohr’s notion that “the best criticism of the bad is the practice of the better.” When we operate within our own sphere of influence, it’s pretty rare that anyone will try to stop us from pushing into new, positive territory. It may not work, but the current reality isn’t working either. Natural Law #9, the idea that success means you get better problems, encourages us to decide which problem we want. Should we stay stuck in the status quo or push toward positive possibilities and see what happens? As you can tell, I’ve tried to teach myself to choose the latter and push past my own ever-present fear. It’s almost impossible, I believe, to see the secret doors without sticking our necks out.

Society, of course, often teaches us the opposite: to stay in our boxes, avoid making waves, and wait for the boss to give direction. In the spirit of what I wrote last summer about the power of ordinary people to make a big difference in the world, I’ll share another bit of insight. It’s from the wise and inspiring Carol Sanford:

This drive to take on things we do not understand or cannot do is inherent in each of us, but it goes to sleep unless it is connected to something compelling, something we can see is needed in a situation that we care about. Once we recognize the need and make the promise to do something about it, the beyond ableness part provides the opportunity and reason to stretch and grow. Proactively seeking to work on things we do not already know how to do may seem daunting at first, but in the long run, it is profoundly affirming.

How, then, do we find the “right” promise to extend our ableness? That’s the quest that Marco Polo has taken up in Invisible Cities. As he says in the book, “At times all I need is a brief glimpse, an opening in the midst of an incongruous landscape, a glint of lights in the fog, the dialogue of two passersby meeting in the crowd, and I think that, setting out from there.”

The visioning process we use and teach so regularly here at Zingerman’s is a wonderful way to bring PBAs out into the open. An effective vision, we believe, must be both inspiring and strategically sound. In other words, it includes many PBAs. They are, by definition, both inspiring to the person pursuing them and strategically sound. A good vision is a big stretch, but we believe we can achieve it! A vision without any PBAs may be very strategically sound, but I doubt it’s going to be very inspiring. I can see now that our 2032 Vision actually has any number of PBAs, including commitments to do effective work around succession and to teach young people our approaches to leadership and life.

Looking back now to our organizational beginnings, Paul Saginaw and I were definitely making a PBA when we opened the Deli in 1982. Neither one of us had ever run one before. Same for the Bakehouse in 1992. We didn’t know much of anything about baking; we just were driven to have better bread! In fact, it just dawned on me that our vision for Zingerman’s to achieve by 2009 is another PBA, one that is based on making more in the future. After all, each new venture we get going on has a whole new specialty we’ve never yet made happen, and it involves working with a new managing partner to make it go. The whole visioning process, and the “hot pen” technique we use to do it, is very conducive to getting clear on the PBAs that, in our hearts, we hope to pursue. As Calvino shared in a lecture at NYU’s Institute for the Humanities in 1983, “In a certain sense, I believe that we always write about something we don’t know; we write to make it possible for the unwritten world to express itself through us.”

Italo Calvino’s life story shaped his fascinating and inspiring approach to writing. He was born in Cuba in 1923, in the years following the Spanish flu pandemic. His Italian parents had emigrated to the island, but when young Italo was four, they moved the family back to their hometown of San Remo, in the region of Liguria on the Italian Riviera. Calvino’s father, Mario, was an agronomist, an anarchist, and a scientist whose work was widely held in high regard. His mother was a very values-driven pacifist who, when the Nazis came to Italy in 1944, encouraged her sons, as Calvino later explained in the essay “Political Autobiography of a Young Man, Hermit in Paris,” to join the Resistance in the name of “natural justice and family virtues.”

When the war ended, Calvino completed his graduate thesis on the writing of Joseph Conrad. Soon after, he started authoring articles for publication and quickly became one of the most remarkable writers of the modern era. In a 1992 piece in The Paris Review, the renowned Italian literary critic Pietro Citati argued that Calvino’s “mind became the most complicated, enveloping, sinuous mind any modern Italian writer ever possessed.” The well-known American writer John Updike said that ”no living author is more ingenious.” Merve Emre, writing in The New Yorker three years ago this month, described Calvino as “word for word, the most charming writer to put pen to paper in the twentieth century.” And, in the years before Calvino’s passing, the novelist John Gardner called him ”possibly Italy’s most brilliant living writer.”

In the winter of 1960, Calvino, by then in his late 30s, came to the U.S. for the first time. After spending a few weeks in NYC, he traveled south, in part to meet Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a man he had admired greatly from afar. By coincidence, Calvino ended up in Montgomery, Alabama, just in time to join the march Dr. King led there that year. Calvino collected his essays from this time under the title An Optimist in America. He seems to have centered himself in his mother’s idea of “natural justice.” Calvino reflected on what he saw take place: “This is a day that I will never forget as long as I live. I have seen what racism is, mass racism, accepted as one of a society’s fundamental rules.”

Over the years, Calvino penned an array of exceptional books and essays, winning awards and acclaim in Italy and around the world. Sadly, he died unexpectedly in September of 1985, after suffering a stroke. He was only 61 years old.

Like anyone who makes great art of any sort, Calvino’s life was, in a way, a series of PBAs that he successfully actualized. PBAs, I’ve come to see, can spring from literal art, like what Calvino makes, or metaphorical art, the sort that every one of us has the ability to create by living our daily lives as artfully as possible. After all, life, as I see it, is art. A PBA that we put into practice can help us go to the next level. In fact, PBAs are always about a long-term learning process, about someone working to master an area of expertise in which they have a high interest but little or no previous experience. A decision to radically diminish the sort of racism Calvino saw in Montgomery would be a great example of what one might commit to doing.

Now that I have PBAs in mind, I can see their impact all over our organization. I remember talking to Lisa Schultz, who would go on to become a managing partner at the Roadhouse, five or six years ago. At the time, Lisa had already worked at the restaurant for almost 15 years, first as a server and then as a supervisor, assistant manager, and front-of-the-house manager. She knew our systems and culture from the ground up and wanted to go to the next level in the organization, but she had zero experience as a business owner. At the time we started talking about her becoming a managing partner, many folks said she wasn’t “ready” yet, technically or tactically. At one point, Lisa said, “I may not always be the fastest learner, but I’ll keep learning until I’m really good at the job!” It was a PBA, and it has played out beautifully. I believed that she could—and would—learn what she needed to know, and I committed myself to supporting her in her development and growth. Sure enough, she keeps getting better and better at her work! She has grown into the role in a wonderful way and continues to grow still every day. The most recent manifestation of all that, is leading the Roadhouse’s extensive renovation project. For those who are in the Ann Arbor area, reopening is still scheduled for some time next week. Stay tuned!

The ZCoB is filled with all kinds of other PBA-driven stories. Ji Hye Kim, managing partner and the chef at the marvelous Miss Kim, came to work at the Deli from the world of health care. She had no experience as either a professional cook or a business owner. Miss Kim was her dream. Fifteen years later, she’s a nationally recognized chef, and the restaurant is busier than ever. Frank Carollo, who taught me to be a line cook around the time Invisible Cities was first released in English, became the managing partner at the Bakehouse when we started it in 1992. At the time, he didn’t know much about baking. But over the years, he became one of the best artisan bakers in the country! The story of Food Gatherers—which was Paul’s idea to start back in 1986, when there were only a handful of comparable food rescue organizations in the country—is another, and anyone who lives near Ann Arbor knows how impactful that PBA has been. I could go on and on with other examples.

My guess is that every managing partner in the ZCoB could tell a story similar to the ones I just mentioned. A few weeks ago, our entire Partner Group took its annual offsite retreat. As I looked around the room, I reflected on how far all of us have come. I think it’s safe to say, in a very good way, that none of the 22 people at the table would have been able to do what they do now back when they started working here. I absolutely include myself in that. What I am writing now, what I am able to see and do and say today, was way beyond my ability back in 1982. There’s no way I would have been able to imagine all of this. Every member of the group has essentially promised, and then delivered, beyond where their ableness was when they joined the organization.

To state the somewhat obvious, all of these stories impact the culture of the ZCoB in a very positive way. When someone new to the organization sees what others have accomplished, the odds of them deciding to do something significant of their own design increase.

My good friend Melvin Parson’s work at We the People Opportunity Farm is great at actualizing PBAs in positive ways. Melvin committed to creating a healthy nonprofit and a successful organic farm without ever having done either. Both he and the community are radically better off for it! Watching him from the outside, I can see that with each PBA he accomplishes, his confidence grows. And shortly after accomplishing a PBA, he commits to a couple of new ones. Now he’s working to open a nonprofit café in Ypsilanti!

By dint of the fact that you’re reading this, you have probably made—and made happen—more than a few PBAs over the course of your life. Our challenge, though, is more about supporting others around us to do the same. A great leader helps craft an organization in which PBAs become the norm, not the exception. Which is, in and of itself, a PBA that any leader reading this might consider committing to. It may not be easy, but that’s the point! Leadership educator Janet Macaluso, who studied with Carol Sanford for seven years, puts it this way:

The PBA: Promise Beyond Ableness.

PBAs aim for what we do NOT know how to do (YET).

But if we were to achieve it, it would increase the ableness and performance of our beloved people, places, or causes.

(so they’re worth it).

PBAs encourage us to commit to something BEYOND current capabilities.

They’re NOT about reckless over-promising.

Promises Beyond Ableness are commitments that:

S-t-r-e-t-c-h us beyond comfort.

Engage innovation on behalf of growing our ECOSYSTEM.

Adopting PBAs as a key organizational ethic is the opposite of the commonly touted Peter Principle. The latter is the belief that people get promoted to the level of their incompetence. PBAs are based, instead, on its inverse: the strongly held belief that when people push themselves to take on something they are passionate about, the odds are high they will learn to do it well. People create their own competence by taking on work they don’t yet know how to do but are strongly committed to getting great at. It’s an internally driven shift rather than an externally directed one. As Italo Calvino said in a talk on March 30, 1983, “Every rite of passage corresponds to a change in mental attitude.”

PBAs are based on the beliefs that:

- Everyone has the ability to grow in multiple ways that exceed their current level of acumen.

- The PBA process will work only when the individual in question commits to the growth because it’s something they are excited about and dedicated to doing.

- The process does not work when others assign the growth. As my friends at Indigenous Resistance write in the beautiful book Mongolia Dub Journey, a PBA emerges when we refuse to be “limited by allowing ourselves to be defined by boxes not of our making.”

- People who aspire to grow beyond ableness work with far greater energy and enthusiasm.

- When people pursue PBAs, their work will benefit others around them. It’s never just an act of selfishness or an attempt to build one’s bank account at the expense of others.

- PBAs help people grow as humans and live more fulfilling lives.

In this context, the leader’s role shifts away from telling people what they should pursue and toward the expectation that each person decides for themselves what they are going to do. A PBA should be something that will help the person, their organization, and the organization’s stakeholders at the same time. The leader must build clarity and confidence rather than focus on command and control. As Sanford writes in No More Gold Stars:

The key to translating all this into change on the ground was a concept that I named promises beyond ableness. Every member of the workforce was encouraged to find an important subject that was relevant to the company’s universe and strategy and, at the same time, was something they cared deeply about. It needed to be a subject that they were willing to work on over the coming years. Put another way, each worker identified and pursued his own long-thought process.

…

When people are developing their ableness and potential, directing themselves using principles calling for personal agency and responsibility, and working creatively in the service of higher purposes that they care deeply about, they are living the ultimate life. They are doing work they value, making contributions that matter, and living in communities and nations [and organizations] that give them the freedom to make a real difference with their lives.

Done well, PBAs have the power to change lives.

In the closing paragraph of Invisible Cities, Calvino’s Marco Polo presents, in a very poetic way, the choice that I believe all of us face: to be frustrated but accept the status quo and go with the flow, or to take on the risky but rewarding challenge of creating the kind of positive futures we hope to have:

The inferno of the living is not something that will be; if there is one, it is what is already here, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the inferno and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space.

The latter of Marco Polo’s two options is, of course, what I have opted to pursue. My new pamphlet, “Why Democracy Matters,” is an effort to find people who are “not inferno,” in the midst of the inferno and give them enduring space in the ongoing huddle in my head. As Calvino writes, it’s risky and demands constant vigilance, but it seems the more positive path by far.

The new pamphlet, I realize now, is also the result of a PBA: my commitment to writing about a subject that I began to see that I cared deeply about but had never written on before. Risky for sure, but the right thing to do. Carol Sanford has this to say on democracy and how it relates to PBAs:

Ableness is the exercise of a skill or capacity at will whenever it is needed. … To grow ableness, a Responsible Business … builds people’s ability to manage their own state of being—their attitudes, behaviors, and ability to remain purposeful. … A Responsible Business next seeks to develop deliberative dialogue and critical thinking skills. … Democratic systems only work effectively when they move beyond the idea that there are only two sides to an issue.

It struck me this week that a dedication to democracy right now requires us all to make a very serious PBA. No American, after all, has rebuilt a healthy democracy at this scale, at least not in this country. This rebuilding requires us to make a collaborative promise beyond our collective ableness. And then deliver on it. We have the opportunity, as Marco Polo says, to make a whole new world from which everyone can benefit.

Near the end of Invisible Cities, the great ruler of the Mongol Empire, Kublai Khan, seeks the sort of straightforward answer from an expert that so many of us have been taught to listen to. He says to the world traveler Marco Polo:

You who go about exploring and who see signs, can tell me toward which of these futures the favoring winds are driving us.

Marco Polo shifts the conversation in a very different direction. The answer we all seek doesn’t come from experts. It emerges from regular reflection, from an intuitive, internally driven sense of the seeker. Polo explains his process:

At times all I need is a brief glimpse, an opening in the midst of an incongruous landscape, a glint of lights in the fog, the dialogue of two passersby meeting in the crowd, and I think that, setting out from there, I will put together, piece by piece, the perfect city, made of fragments mixed with the rest of instants, separated by intervals, of signals one sends out, not knowing who receives them. If I tell you that the city toward which my journey tends is discontinuous in space and time, now scattered, now more condensed, you must not believe the search for it can stop. Perhaps while we speak, it is rising, scattered, within the confines of your empire; you can hunt for it, but only in the way I have said.

I believe that together, we can do much more than most people believe possible. As I explain in the new pamphlet, I am ready to get going! I have had a brief glimpse of what is possible, an opening in the midst of apparent incongruity. You and I, we can hunt for the “cities” we seek. If we keep looking, we will find the secret door. It’s out there, waiting for us to do our work.

Craft a vision of greatness

P.S. I’ll be doing a book talk on Thursday, March 5, at Darius Smith’s new Ohana Lounge in Ypsilanti. It’s about the soon-to-be-released “Why Democracy Matters” pamphlet. The conversation kicks off a bit after 6 pm! We’ll have copies of the new pamphlet and other Zingerman’s Press books for sale and signing. Hope to see you there!