Tag: ARI WEINZWEIG

Lessons from the Paris Commune of 1871

Scholar Henry Giroux, who turned 82 two months ago last week, wrote recently that “Americans have forgotten what democracy is about.” What follows is an exploration of one way we might help ourselves, and the people we work with, to remember. To be clear, it’s not about what happens in Washington. This is about our workplaces. It’s about what we can all do to help everyone in our organizations better engage in the kind of free thinking that any effective democratic construct calls for, whether it’s in a small company or a large country.

To put it another way, this essay is essentially about class. Not in a class-war kind of way, though. This is about the work the Zingerman’s Community of Businesses (ZCoB) does to offer an array of insightful classes. Classes about everything from food philosophy to finance, customer service to courageous conversations. The key here is that the many dozens of classes we offer are available to everyone in our organization. As one coworker once told me,

I have never before talked to the owner of a company I was employed at about my personal life goals. The owners of Zingerman’s not only reinforce them, they pay me to take classes to make them happen. Literally, they pay me to better my personal life. That’s totally crazy.

After decades of doing this, it’s very clear to me that all this class work we do alters our business for the better and improves the lives of the people who work here. I am also confident in saying that it strengthens our community and our country. Lately, though, I’ve noticed that their significance—and the fact that we open them to everyone in the organization, regardless of job title, age, or seniority, and pay them to attend—is far greater than what I’d assumed before.

In a piece published two years ago in The Paris Review, the remarkable writer Hanif Abdurraqib—who I admire greatly for passing on the publicity that might come with moving to the East or West Coast, as many artists do, and instead staying rooted in his hometown of Columbus, Ohio—commented on the state of the country. In his words, our society “is obsessed with punishment, particularly for the most marginalized.” As I reflect on what dominates the news and current national trends, what Abdurraqib wrote resonates. It is a difficult reality to get my mind around. As Sarah Harris from the band Dolly Creamer sings in her song “Live in There,” “We’re in a movie that does not move me.”

There are many places, of course, that we can collectively help those who have less. As psychologist Abraham Maslow pointed out in his oft-referenced Hierarchy of Needs, food, shelter, and safety are always the most critical concerns for anyone living on the edge of physical survival. Beyond that, though, Abdurraqib’s insightful comment made me curious:

- What would it look like if, instead of prioritizing punishment and retribution, our society was instead obsessing over education and learning?

- What if businesses across the country were willing to teach finance and philosophy and Servant Leadership and the like to everyone in an organization, from entry-level staff to upper-level managers, helping them think like leaders and engage with complex issues in creative and challenging (in a positive sense) ways?

- What if many of those classes were not just about teaching specific job skills but rather about helping people learn to think? What if they helped people at all levels of the organization grow into themselves and become actively engaged with the sorts of philosophical issues that are usually left to upper-level leaders to grapple with in more formal settings? These kinds of learning opportunities are rarely offered to folks on the front lines. What if making them readily available to all became the national norm?

I realize that we’ve been trying to answer these questions in our day-to-day lives at Zingerman’s for many, many years now. It’s impossible to isolate the impact of all those classes from everything else we do, but I have no hesitation in saying that it’s hugely significant. Without our constant focus on learning and teaching, we would be a very different organization. The classes we teach are, in a sense, another entrée into the benefits of the regenerative studying I wrote about a few weeks ago. They support the growth and development of many dozens of us—probably more, actually—who work here every year!

Our decision to offer so much training came out of our deeply-held belief that people want to learn, that when people are thinking more clearly and cohesively, they feel better and do better; and that everyone in the organizational ecosystem—customers, neighbors, vendors, and community—benefits in the process. We did it because, to us, it just seemed to be the right thing to do. It was intuitive. That said, there’s recent data to back up our long-standing belief. This past spring, the Harvard Business School wrote that “Research shows that companies experience a 17 percent increase in productivity and a 21 percent boost in profitability when employees receive targeted training. … Teams feel valued, empowered, and motivated. This sense of purpose fuels a culture where growth, collaboration, and innovation flourish.”

The idea of constant learning is deeply embedded in the essence of our organization. We like to learn. We want to understand why things are the way they are now and also how they got that way. History major that I am, I’m happy to say that nearly every class we teach includes some history. I will share a whole bunch of that next Tuesday night when I teach my annual Best of 2025 tasting class at the Deli.

Speaking of history, Henry Giroux started his career in education as a high school history teacher. He warns that “The dominant culture actively functions to suppress the development of a critical historical consciousness among the populace.” History, he reminds anyone who’ll listen, has important lessons to teach us:

We need to realize that if you can’t learn from history, you go beyond the cliché of simply repeating it; you find yourself in a place of danger in which historical consciousness and its relevance turns to historical amnesia. … The United States suffers greatly from historical amnesia.

With Giroux’s warning in mind, I’ve had a realization of late. It happened while studying the history of the remarkable 19th-century French activist, anarchist, and educator Louise Michel. More than ever, thanks to her impassioned writing and speaking on the subject, I can see the import and impact of our efforts to make classes and other forms of learning widely available to everyone in the organization. In her memoirs, published in 1886, Michel wrote that the powers that be in society “do not want to share the sweetest thing of this old world: knowledge and learning.” For Michel, education was as important as eating. As she put it, learning about anything from painting and poetry to physics and philosophy should not be the province of a privileged few. “Art, like science and liberty,” Michel wrote, “must be no less available than food.” To Louise Michel, education was liberation. And, in a sense, I can see now that in a quiet, easily missed-by-many way, offering so many learning opportunities to everyone who works here does just that.

Louise Michel was born in 1830 in the town of Vroncourt, in the Haute-Marne, in the northeast part of France. The daughter of a poor single mother living in a rather remote region, she loved both animals and learning from the time she was a child. In 1861, when she was 31, Michel moved to Paris, and in 1865, she opened a progressive school there. The mid-19th century was an era in which thousands of people were leaving their villages, abandoning old craft trades to take newly created-in-the-Industrial-Revolution factory jobs in cities. These were workplaces where what mattered most was one’s ability to persevere through mind-numbingly repetitive and physically challenging tasks. Wealth was created, but most of the world was worse off for it. As historian Mark Cartwright explains:

The workforce became much less skilled than previously, and many workplaces became unhealthy and dangerous. Cities suffered from pollution, poor sanitation, and crime. The urban middle class expanded, but there was still a wide and unbridgeable gap between the poor, the majority of whom were now unskilled labourers, and the rich, who were no longer measured by the land they owned but by their capital and possessions.

Writer Chip Bruce has picked up on Louise Michel’s magic. Bruce, who’s very active in a program called Democratic Education in the 21st Century, writes:

She was an early practitioner of what I’d call inquiry-based learning. She was a continual learner. … As a schoolteacher, she used methods promoted in the progressive education movement (which came much later): interaction with objects such as flowers, rocks, and animals, studies outdoors, and scientific methods. … Michel wanted students to learn to think for themselves, just as she did herself and encouraged others to do throughout her life.

Louise Michel had the radical belief that the flow of learning should be reversed. Instead of being done only for those at the top of society, Michel believed that creative education ought to be available to anyone who was interested. She imagined a future in which art, learning, and science would belong to all people, not just a privileged few. As she explained:

Genius will be developed, not snuffed out. Ignorance has done enough harm. … The arts are a part of human rights, and everybody needs them.

A century and a half or so after Louise Michel said that, there is still a great deal of wisdom in her words, wisdom that any forward-thinking 21st-century organization of any size would be able to benefit from. Classes, books, conferences, libraries … all can be made as available to people in front-line jobs as to those in formal positions of power. As Louise Michel wrote in her Memoirs, charity was not the answer. “What we do want,” she wrote, “is knowledge and education and liberty.”

Carol Sanford, who passed away a year ago this month in her mid-80s, was, I believe, as radical in the world of modern business philosophy as Louise Michel was in mid-19th-century France. Sanford, like Louise Michel and Henry Giroux, was always very direct in her criticism of mainstream practices. As she put it: “The way most companies manage their workforces is bad for business. Not coincidentally, it’s also bad for people and for democracy.”

Among the many things Sanford helped me to understand is the import of what she calls “indirect work.” While most businesses—both in Louise Michel’s era and our own—focus primarily on work that will directly and immediately impact financial results, operational effectiveness, or both, Sanford was adamant that those efforts must be accompanied by those that are wholly indirect. As she explains in her book Indirect Work:

Indirect work is inner work … It is about change inside each of us, in the ways we perceive and understand the world and our roles and responsibilities within it. … Profound change rarely comes from direct interventions in the world. Rather it comes working indirectly over time, helping people engage consciously to develop their own understanding, motivations, aspirations, and will. All sorts of human endeavors can benefit from this approach.

The kind of broad educational activity that we do here in the ZCoB is a great example of what Sanford is suggesting. It’s hard to prove exactly how a new staff member attending a class on self-management increases sales or how a sandwich maker taking a class on personal visioning will change our organization. Still, per what Carol Sanford is saying so clearly and what Louise Michel understood intuitively, I am confident that it makes a hugely meaningful difference! It helps the people who work here grow as human beings and as leaders, which in turn helps power our organization. As Sanford explains:

Development works on our ability to be awake with regard to ourselves, and this is inherently indirect. … The role of development, to cultivate the capacities for self-observation and conscious choice that enable us to show up as living, creative beings in a living creative world, to be self-determining rather than predetermined.

With Louise Michel’s words in my head, I’ve been realizing anew how important our extensive class offerings really are. And how radical it is that nearly all of these classes are offered to anyone who works here who’s interested. Henry Giroux reminds me how much impact effective education has on the greater ecosystem around us. He’s not just referring to the accumulation of knowledge. Like Louise Michel and Carol Sanford, he’s advocating for social constructs in which self-awareness, empathy, and emotional intelligence are important. As Giroux said in an interview with Julian Casablancas, lead singer of The Strokes: “I want to see people who exhibit two things—a sense of self-reflection and a sense of compassion for others.”As he reminds us, democracies “cannot survive without informed citizens.”

Conversely, I think it’s also right to state the ethical inverse: “An autocratic leader cannot stay in power when its citizens are well informed.” People who have learned to think for themselves, who value their views and the views of others, don’t want to blindly follow a boss who tells them what to do. As Louise Michel said, “The task of teachers, those obscure soldiers of civilisation, is to give the people the intellectual means to revolt.” And that, we can be sure, is not what autocratic leaders of companies or countries would want.

Over our 40-plus years in business, we’ve worked hard to support learning and education in as many ways as possible. One thing we do regularly is send ZCoBbers to various conferences over the course of the year. While we don’t, of course, send all 700 people who work here to conferences every year, we do send a pretty high percentage of people compared to a lot of organizations. The opportunity to learn and make new, creative connections can be incomparable. When I think of all the individuals I have met at conferences where I have been a speaker, it’s kind of mind-blowing. With all that in mind, I try to imagine the experiences that a 26-year-old Emma Goldman had as an up-and-coming American immigrant activist. In September of 1895, at which point she’d lived in the U.S. for about a decade, she was traveling to London to speak at an anarchist conference. After spending 10 days crossing the Atlantic on a steamship, Emma met Louise Michel, a woman who had, by reputation, inspired her for many years. Almost a quarter century earlier, Emma Goldman was a 6-year-old girl in Lithuania when Louise Michel was 41 and fighting on the barricades of the Paris Commune. At the time of the conference, Louise Michel had already had a lifetime of amazing experiences. She celebrated her 65th birthday that year.

The bright moment of the Paris Commune, which started in March of 1871, came to an end that May, when its democracy-seeking supporters were beaten back and then arrested and imprisoned by royalist forces. Writer Adam Gopnik calls it “one of the four great traumas that shaped modern France.” For a few short months, though, anarchists, socialists, and other free thinkers like Louise Michel created a free, non-hierarchically governed city that came to be called the Paris Commune. The Commune got rid of the idea of higher-ups and instead ruled, like the Serbian student movement is doing today, with elected bodies, or what the Serbians call plenums. To this day, the Paris Commune is remembered positively—along with Barcelona during the Spanish Civil War—as an effective, anarchistically oriented, on-the-ground experiment in real-life non-hierarchical governance. And Louise Michel’s courage and creative leadership became a big part of its legend.

In the final weeks of 1877, Louise Michel was put on trial in Paris for her role in the fighting for freedom with the Commune. The opening lines of the trial’s transcript are telling:

The Court. — Your age?

Louise Michel. — Forty-seven.

The Court. — Your profession?

Louise Michel. — Teacher and woman of letters.

While her emphasis on education has clearly impressed me, it did not impress the French court. Michel was convicted and sent to a Paris prison for two years, then put on a ship and sent off to the penal colony on the French-controlled island of New Caledonia. There, Michel again took up teaching, including teaching French to the indigenous Kanak people, not to “civilize” them but rather to give them a tool they could use to advocate for themselves with the French authorities. I wrote a good bit about the value of teaching a few years back, in an essay entitled “Why Leaders Should be Teachers.”

Louise Michel says education’s purpose is “the formation of free men full of respect, and love for the liberty of others.” Looking back on our collective life here in the ZCoB, it strikes me that one of the more radical, impactful things we have done to make our culture what it has come to be is teach a wide range of classes for the people who work here. These classes are, for the most part, open to anyone who wants to go. I’ve lost track of how many we offer, but there are a lot. I lead the Welcome to the ZCoB orientation regularly. There’s Intro to Visioning, where people learn how to write the story of the future they want for their personal lives, work projects, or both. There’s our most oft-taught class, The Art of Giving Great Service. We have a diversity class that we teach diligently every month. There’s a class on Servant Leadership. Two or three classes on Open Book Management. There’s another on personal finance. There’s a class called Managing Ourselves. And everyone who works here has free access to any of the 20-plus online ZingTrain Virtual Workshops. Two weeks ago, right after I had my tooth taken out, I taught the Welcome to ZCoB Governance class to go over the imperfect but very intentional democratic practices we use. These are just the classes I can come up with off the top of my head.

It is, I know, a long list, one that’s likely intimidating to anyone who is considering teaching some internal classes in their own organization. For context, though, remember that we’ve been here nearly 44 years. Even two well-run classes in a small company can make a big difference. We did not create this kind of class list in a couple of weeks. The point is not to have the longest class list in town. It’s to get started, to teach and learn, to get people thinking, to encourage them to ask questions, and to learn to think like leaders instead of waiting for direction.

Right now, this is not the popular mainstream approach. As Henry Giroux writes:

Authoritarian societies do more than censor; they punish those who engage in what might be called dangerous thinking. … Critical and dangerous thinking is the precondition for nurturing the ethical imagination that enables engaged citizens to learn how to govern rather than be governed. Thinking with courage is fundamental to a notion of civic literacy that views knowledge as central. … Thinking dangerously is not only the cornerstone of critical agency and engaged citizenship, it’s also the foundation for a working democracy.

It’s also, I would suggest, critical for creating the kind of organization we envision. Nearly all of those classes, it seems to me, are focused mainly on providing frameworks to help people learn to think for themselves and to develop their own philosophies and worldviews. Informed staff members, as I have experienced them:

- are more willing and able to engage in thoughtful conversation

- are better able to creatively and caringly question the status quo

- learn how to think systemically

- offer insights into how to improve pretty much every part of what we do

- have learned how to lead the implementation of those improvements

- get to know what good meetings are like, which means they learn how to participate effectively in a range of constructive conversations—the kind it takes to run any democratic and inclusive organization

- can handle more complexity and paradox when making decisions in difficult situations

- learn to think like leaders

- learn to self-manage, to be reflective, and to be responsive to requests

- tend to offer constructive ideas and approaches rather than just offering a critique

The impact on the country and our communities is substantial: People who learn these things at work are very likely to practice them when they go home, too. They become more active and effective citizens. They generally do not advocate autocracy. They want to think for themselves, not just blindly follow orders from above. The long-term, big-picture effect is indeed indirect, but over time, it’s hugely impactful, and to me, greatly inspirational. As Carol Sanford writes in The Regenerative Business:

Businesses that foster initiative and self-management change forever the way employees look at the world. When people spend their lives in hierarchical systems with supervisors making decisions for them, their decision-making capacity and their confidence in their own judgement weaken. They become habituated to ceding control and responsibility to authority figures. … By evolving the natural source of human creativity and responsibility, a regenerative business builds more than itself. It grows better citizens and, as a result, it builds a better nation and a better world.

What do we get out of all this? I recently asked one staff member what she thought about the fact that we teach so many classes internally. She smiled a bit and said, “I love it! It’s one of the best parts of working here! I think everyone should take as many of the classes as they can.” A coworker standing nearby who happened to overhear us chimed in, listing the various classes he’s taken, too.

Henry Giroux, who I believe is one of the most important thinkers of our era, said in an interview last year:

If I think about the future, I want to think about conditions that produce the Martin Luther Kings, the Gandhis, that produce massive movements, that produce great filmmakers, great educators, great women, great men who struggle together in a way that is self-consciously benevolent and compassionate. That’s what I want.

Creating an extensive program of internal education is not all it takes to make that happen. But it’s certainly a darned good start. A start that, as Giroux, Sanford, and Michel all highlight, will help create the conditions we need for healthy democratic engagement, both inside our companies and in the country at large! The training and learning work we do in this context today could help someone who’s currently making sandwiches or slicing salami become the next Henry Giroux, Carol Sanford, or Louise Michel. Who knows, someone who leads the work to change our country could be inspired to action by a class you start teaching two or three weeks from now. As Louise Michel says:

That something has never happened before certainly does not mean it is impossible.

Learn about leading with intention

Tag: ARI WEINZWEIG

Cut-up poetry and prioritizing joyfulness even in the face of pain

In 1951, the American Surrealist artist, author, and poet Dorothea Tanning, working in the very special light of the cabin that she and her husband, the artist Max Ernst, had built in Sedona, Arizona, completed a 2-by-3-foot oil-on-canvas painting. She called the piece “Interior with Sudden Joy.”

The painting, like all of Tanning’s work, and for that matter, her whole life, is remarkable. The title, though, is what caught my attention. Joy, for a whole range of reasons that I’ll share below, has been very much on my mind.

Tanning once opined that “art has always been the raft onto which we climb to save our sanity.” Her image of an interior existence being regularly brightened by sudden bursts of unexpected joy is, well, giving me joy, and also a bit of much-needed sanity while I work to cope with the rather frightening flow of current events in the greater ecosystem around us.

Joy was not something I remember being taught about as a child, but I learned later in life that joy matters far more than I would ever have imagined. While it’s not taught in too many business school settings, joy is actually an essential element in the making of a healthy organization. In fact, joy fits nicely into #12 on the list of Zingerman’s Natural Laws of Business:

Great organizations are appreciative, and the people in them have more fun.

With that understanding in hand, I have worked hard for many years now to make the title of Tanning’s painting come alive—to have an interior life regularly punctuated by bursts of unplanned joy! And, as best I can, help make similar joyful experiences a regular reality for everyone who works in our organization, and for all of our caring customers as well.

Half a century after she finished the painting in Arizona and a few months after she had turned 83, by then living in Manhattan, Tanning was interviewed by writer Jane Kramer for a piece that was later published in The New Yorker. Near the end of the essay, Kramer asks Tanner about the flow of her writing, in particular her poetry. “Well, sometimes,” Tanning explains, “an idea keeps rolling around in your head, or a pair of words, but you don’t really know what it is. It has to emerge.”

I can absolutely relate. Thanks, in good part, to stumbling on the title of Tanning’s painting, joy emerged as the topic of this essay after rolling around the rocky corners of my mind for the last couple of weeks! In these challenging times, as we try to figure out how to lead effectively, living out Tanning’s title is, I believe, an essential act of existential health. It’s true for each of us as individuals and for our organizations as well.

It might seem strange—or, to some cynics, sort of silly—to focus any of our limited attention on joy when there are so many other issues that seem more pressing. I, of course, take the opposite approach. Joy has the power to transform organizations and the lives of the people who are part of them.

My friend Rich Sheridan, co-founding partner of Menlo Innovations here in Ann Arbor, literally wrote the book on joy. Actually, he wrote two: Joy, Inc. and Chief Joy Officer. I have found what Rich writes to be right on: “The journey to joy at work is personal. It has to be. You want a job or an organization that brings you joy.” Even if they’re not conscious of it, people want to frequent joyful businesses and live in joyful communities and countries. And while the news may not reflect it much right now, joy can and does remain a healthy, positive, uplifting, smile-evoking, eye-opening act of resistance.

If you doubt the power joy can have on a national level, check out the history of Chile. Frank Greer, the founding partner of the progressive global consulting firm GMMB, worked extensively with the fledgling Chilean democracy movement that went on to unseat the longtime brutal dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet through an effective electoral process back in the late ’80s. In a retrospective he wrote two years ago this coming February, Greer noted:

The slogan “Chile, joy is coming” signified a bright future with democratically elected leadership, the rainbow logo illustrated the many parties working together and the inspiring music captured the hope of the nation. … [These efforts] brought joy and democracy back to Chile!

If joy can change a country, I’m confident it can effectively alter our organizations as well. Whether it’s in companies or countries, joy is an effective strategic tool for anyone who wants to improve their quality of life and bring more dignity and democratic practices into play. NYU history and Italian studies professor Ruth Ben-Ghiat writes, “Joy is precious and noble and also the basis of effective anti-authoritarian strategy.” In 1988, roughly 2.5 million people in Chile (nearly a third of the country’s voters) participated in what was widely known as the “March for Joy.” On October 5th of that year, the pro-democracy program won nearly 55 percent of the vote while 43 percent went to the military dictatorship. The government had the guns and a grim determination to hold to power; the democratic opposition, though, won the day with joy front and center. I smile now, realizing that Lucinda Williams’ classic song “Joy,” released a decade later in 1998, summed up the whole situation:

I don’t want you anymore, you took my joy

You took my joy, and I want it back!

The power of joy has been effectively exercised far closer to home as well. In the second week of December 2009, writer Toi Derricotte, who grew up in the Detroit neighborhood of Hamtramck, posted a poem entitled “From the Telly Cycle.” Dedicated to her beloved pet fish that had recently passed away, it leads with the line “Joy is an act of resistance.” That poetic pronouncement has since been used by others, but it seems that Dericotte was the first. It would go on to become a significant slogan of what came to be called the Black joy movement. Professor of African American Studies Mei-Ling Malone makes clear that “Black joy is an act of resistance. The whole idea of oppression is to keep people down. So when people continue to shine and live fully, it is resistance.” Joy, it turns out, is both more fun and a powerful force for change—both individually and collectively— at the same time.

All that said, these are not, I know, the easiest of times in which to focus on and feel joy. When anxiety is high, when costs are rising, and consumer confidence is dropping, when national leaders are known to be lying, when innocent people are getting iced right in front of our eyes, it would be easy and understandable to feel down. Some days, some hours, and some other times, too, I most definitely do. My determined focus on finding joy, though, helps me get through. It keeps me focused, determined, and resilient. It makes my eyes light up, and my smile grow wide, no matter what is going on in the world around me. Joy, for me, is an essential ingredient in resilience and resistance both. Without joy, my internal ecosystem suffers; with it, everything goes better. Joy doesn’t just immediately make all the challenges we face go away, but it does give me the energy to deal with them far, far more effectively.

Having spent many years now studying the subject, both in my own life and in our organization, I can say with confidence that you can feel the difference joy makes. This little story from last week reminded me how much of a difference.

Two weeks ago tomorrow, I cracked a tooth. My caring dentist came in on her day off to take a look. Ten minutes into treating me, she delivered the bad news: The tooth had already been filled twice before; there was really no way to save it. Taking it out, and then the rather intimidating insertion of an implant, she said, would be next. The following Thursday afternoon, I had the tooth extracted. It’s not the most painful thing I’ve experienced, but it wasn’t all that much fun either. Pain followed, as expected. Being like jazz musician Pharoah Sanders, Sarah Harris of the band Dolly Creamer, and the other inspiring folks I wrote about a few weeks ago, artists and leaders who keep going even in tough and awkward times, I went back to work that evening. Since it wasn’t going to be any less painful sitting at home, I figured I’d just power through at work, where the bustle of a big dinner rush at the Roadhouse could take my mind off it. I gritted my teeth (metaphorically, given the circumstances), got centered, smiled, and decided to make it a great evening anyway.

A little before nine that night, I found myself in conversation with a nice young couple, first-time guests from Ohio who were dining at a table across from me while I worked on the computer. Turns out I know his parents, both longtime chefs from Chicago. He and I had a lovely chat, with my tooth—or the spot where my tooth had been—quietly throbbing in my head the whole time. When the couple was leaving—heading to Bay City to see Jerry Seinfeld and likely having a very joyful evening—he and I shook hands and agreed to stay in touch. He looked me in the eye, and with a wonderfully grounded, sincere energy and a big smile, said, “You really seem like someone who just feels so much joy!” Caught off guard in a really good way, I smiled back, surprised that despite it all, joy—not tooth pain—is what came across. In hindsight, I realize that what happened was Dorothea Tanning’s title come alive. Despite the pain from my missing tooth, my emotional interior was immediately made brighter by this sudden burst of joy. And it was a great reminder that, in a focused setting, joy will trump pain. I’m fortunate, I know, to live in a joy-filled ecosystem where situations like this are so much more likely to happen. Not everyone has the same opportunity. I have learned, though, that joy isn’t something that happens to us. Rather, it’s something we need to actively look for. Far more often than most people realize, even in hard times, joy is there for the appreciating. If we don’t pay attention, it passes us right by.

Having spent 25 years learning to tune in and notice joy, I tend to stumble on it almost everywhere I turn. Sure enough, sudden interior joy showed up for me a couple of days after the tooth incident, at about 7 pm on Saturday. During a quiet couple of minutes, I checked my email, where I found a lovely note from my East African friends at Indigenous Resistance (IR). I closed last week’s essay about the import of Edgewalking in the modern world by citing the exceptional way that IR exemplifies the willingness to engage with intriguing and interesting worlds, ideas, cultures, and more. The regenerative study I had engaged in to write the piece had already brought me a great deal of joy. But, as Dorothea Tannin’s writing reminds me, there is more to almost every story than it might seem. She would regularly tell anyone who was listening to stay open and curious, “Behind the door, always another door…” And, sure enough, another door into this already good story about Edgewalking unexpectedly opened up for me. My evening was brightened by this email from the other side of the Atlantic:

Greetings in Dub

Hope all is well on your end

I wanted to share something truly amusing with you.

I was reading your latest newsletter and really really loving it, especially when it came to the section with the Vietnamese artist having lived in Vietnam. … I caught the dub of when he’s using artillery shells to make beautiful sounds. But here’s the dub. As I was reading what you were writing about moving between different worlds and edges and actually liminal is one of my favorite all time words.

I was reading it and thinking my goodness this is so dub, this is so what IR is about. I need to write him to tell him I appreciate it and then I read the next paragraph and it’s about IR.

I couldn’t stop laughing 🙂

I laughed right back when I read it. I couldn’t not smile seeing that the writing had connected. The note touched my heart. Joy, of course, ensued. I think anyone who makes art will be able to relate. We make art for ourselves because we believe in what we’re writing, singing, sculpting, cooking, and so forth. Still, knowing your work has resonated with someone you respect a great deal tends to bring a lovely bit of sudden joy. It’s something I’m always happy to experience!

While experiencing joy is a wonderful thing, its absence can be painful. Dorothea Tanning grew up in the very conservative community of Galesburg, Illinois. It was, apparently, a rather joyless place. Journalist Richard Howard reports that Tanning would say, “It was a life unsweetened by culture,” and, as Tanning told it, “Where nothing happens but the wallpaper.” If my friend Shawn Askinosie is correct that our life’s vocation is nearly always the healing of our childhood wounds, Dorothea Tanning delivered in style: she went on to live a remarkable, productive, vibrant, joyful, and joy-filled life until she passed away in the winter of 2012. Tanning was 101, and making art right up until the end.

In 1920, at the same time that Tanning was turning 10 in central Illinois, on the other side of the Atlantic, the Jewish-Romanian anarchist poet Tristan Tzara had just celebrated his 24th birthday. The previous year, Tzara, who would later turn out to be one of Tanning’s artistic influences, had left his native Romania and moved to what one could consider the spiritual opposite of Galesburg: Paris. There, Tzara turned out an abundance of edgy, intriguing artistic work.

Tzara, who was instrumental in founding the Dada art movement, is a joy for me to study. Tzara was born Samy Rosenstock in the Romanian town of Moinești. At the time of his birth, roughly half the town’s population was Jewish. Thanks to my friend, Alabama-based Romanian poet Alina Stefanescu, for turning me on to Tzara’s work. Anyone who knows me even moderately well will immediately recognize how regenerative study—especially reading about Tzara’s life—has evoked an enormous amount of joy. After all, Romanian Jewish artists and anarchist poets are not a dime a dozen. Tzara, like Alina Stefanescu and Dorothea Tanning, is one of a kind. How could I not be fascinated by a guy who once wrote that “morality is the infusion of chocolate into the veins of all men”?

In 1920, Tzara penned a piece called “How to Make a Dadaist Poem.” It was a day-to-day way to take the Dadaist philosophy that he helped pioneer, and put it to work. Tzara put the instructions in poem form:

Take a newspaper.

Take some scissors.

Choose from this paper an article of the length you want to make your poem.

Cut out the article.

Next carefully cut out each of the words that makes up this article and put them all in a bag.

Shake gently.

Next take out each cutting one after the other.

Copy conscientiously in the order in which they left the bag.

The poem will resemble you.

And there you are—an infinitely original author of charming sensibility, even though unappreciated by the vulgar herd.

While it may sound silly, a whole series of rather famous people have used and advocated this “cut-up” technique. Writer William Burroughs is one. David Bowie is another. In fact, the famous line “I’m an alligator” in Bowie’s early ’70s classic “Moonage Daydream” seemingly came from practicing Tzara’s method. Given my recent work around poetry and desire to lean into Dorothea Tanning’s idea of an interior filled with sudden joy, I challenged myself to follow Tzara’s recipe.

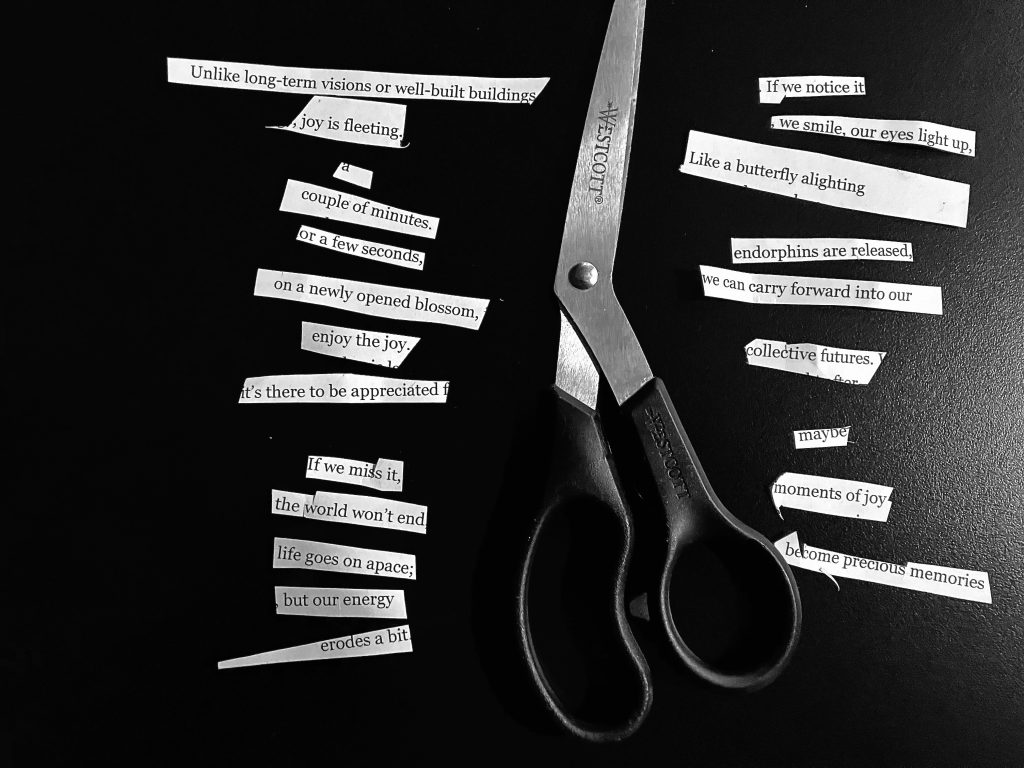

To get going, I printed out the piece I wrote on joy in this newsletter a few years ago. The beginnings of what I created from the cut-up are in the photo above, but here is the whole joy-evoking poem. To be clear, other than the title, all the words were already on paper—all I did was cut and then arrange them in an order that resonated. Sure enough, joy ensued as I assembled (or, I suppose, reassembled) the pieces:

A Bit of Romanian Dadaist, Jewish, Anarchist Poetic Joy for the 21st Century

Unlike long-term visions or well-built buildings

joy is fleeting

a

couple of minutes

or a few seconds,

on a newly opened blossom,

enjoy the joy

it’s there to be appreciated.If we miss it,

the world won’t end

life goes on apace;

but our energy

erodes a bit.If we notice it

we smile, our eyes light up,

like a butterfly alighting

endorphins are released.

Maybe

moments of joy

become precious memories.

we can carry forward into our

collective futures.

In his “Dada Manifesto 1918,” Tzara reminds us that “everybody practices his art in his own way.” Performer Patti Smith happens to be particularly good at it. In a recent interview with the New York Times’ Ezra Klein, Smith put the current state of the country in perspective and showed how she connects to joy in the face of adversity:

Despite everything that’s happening in the world and everything around us and any frustration or helplessness we feel or betrayal we feel, we have to remember it’s also all right to feel the joy of being alive and feel the joy of your own possibilities. Even in the face of the suffering of so many people around us.

Smith, who Spin Magazine called “a cross between Tristan Tzara and Little Richard” after an interview in March 1979, also reflects on her long career as a performer and poet: “I feel grateful because people are still interested in this work that was committed half a century ago. It’s a lot of joy.” Of the many loved ones she’s lost over the years—her husband Fred, her brother Todd, her lover and friend Robert Mapplethorpe, her longtime pianist Richard Sohl—she says, “They remain within me. And I can still access joy.” Providing more evidence that those who do well in life can find joy in the face of adversity, she continues, in an expression and explanation that sounds remarkably like what we might say here in the ZCoB:

Despite that [loss], I feel also the joy of celebration—and happy to be here, happy to be physically able to do it, to feel my voice is strong and that I can give the people, as authentically as I can, the experience of the record as a new experience every night. I want everyone who comes in wanting a special night to leave feeling that it was a special night.

Speaking of special nights, I am reminded with great regularity that joy will almost always appear at some point, and usually in ways that I least expect it. I just have to be paying enough attention to notice it.

To wit, on a rather mundane mid-autumn Tuesday evening, I ran into a family with two young daughters. The youngest, maybe 10 years old, was celebrating her birthday. When asked where she wanted to go for dinner, she chose the Roadhouse. That, to me, is one of the best compliments a restaurant can get. Curious, I asked what she had for dinner. With a big smile on her face, she rattled off the elements of her birthday meal: “The salmon. And mashed potatoes. And spinach. It was really good.” Lo, that I had been that into food when I was her age! For me, that sort of thing is far more meaningful than an award. Joy at its hospitality-focused best.

About 10 minutes later, dining room manager Zach Milner, who was expediting that evening (assembling orders, checking for quality, and sending them out into the dining room), asked me to run a lone fried chicken leg over to table 206. When I got to the table, I saw a new mother with a relatively young infant. The child was holding another chicken leg tightly in her fist and awkwardly but passionately eating it. She was far too young to talk, but the message was clear. The mother smiled and said, “I gave it to her to try a bite. She’s never eaten chicken. And she ate the whole thing!”

Sometimes, of course, joy comes in these beautifully upbeat and innocent moments. But it’s of equal import when we’re struggling with a serious issue and unsure of how to move forward. Nearly a century ago, Tristan Tzara gave some advice that our whole country—me included, of course—could take to heart. “Let us try for once not to be right.” Instead, we can listen with open hearts and remember that joy is a part of living a good life, even in stressful situations. We can, in that context, skip the lectures and instead lean in and then learn some more. If we’re paying attention, the odds are pretty high that some joy will ensue. Choosing joy, even in the face of adversity, is one of the best ways we can lead positive change.

Last weekend, the campus newspaper at the University of Toronto ran an article by student Augustus Crysler-Hill entitled “Indigenous Joy, The Backbone of Colonial Resistance.” In it, Crysler-Hill writes:

I believe that it’s important to recognize Indigenous joy as an essential part of colonial resistance. … I consider the joy and humour that are present in Indigenous cultures to be resistance in multiple ways. … By expressing this joy, Indigenous peoples show that they are still alive and well and reject the societal narrative that Indigenous peoples are simply victims of the past.

Indigenous joy is not only important in the context of resistance, but also due to its healing and connecting qualities. Laughter serves as a connection between family members and is key to Indigenous communities. It gives relief in times of hardship and allows our people to discuss traumatic events.

In the metaphorical organizational ecosystem pamphlet I’m partway through working on, butterflies are akin to joy. They show up in abundance in healthy ecosystems and are diminished on land that is not healthy. And because butterflies flutter past so quietly, we need to pay careful attention. If we don’t, the joy flutters past, and our lives are a bit poorer for having missed it.

If butterflies are joy, a lovely one landed on the back of my metaphorical hand as I looked deeper into Tristan Tzara’s life. It turns out that Tzara was, for a number of years, also active with the Symbolist movement. As a young man, Tzara—at that point, still in Romania and known as Samy Rosenstock—even helped cofound a Symbolist magazine. As you may remember, symbols have really been on my mind a lot in recent months. Tzara, it turns out, also used butterflies as a symbol in the Dadaist philosophy he helped to frame, noting that “Dada covers things with an artificial gentleness, a snow of butterflies.”

On the 5th of May, 2012, Patti Smith, who I now keep thinking of as “the Tristan Tzara of punk,” played her first show in Mexico. It was held in what had been the home of artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Journalist Guillermo Urdapilleta writes that Smith, who had turned 65 six months earlier, performed “with evident joy.” Her joy, it seems, was contagious. By the end of the evening, Urdapilleta reports, the audience had become “a joyful mass with a wonderful vibe.”

The night before the show, dealing with pain from a fall the previous day, the staff at the house had suggested that Smith sleep for a bit in Kahlo’s bed to rest her body. While she was sleeping, she dreamed of a poem. The next morning, she wrote it down, calling it “Noguchi’s Butterflies,” inspired by the butterfly collection that Kahlo had hanging on the ceiling above her bed. The butterflies were gifted to Kahlo, many years earlier, by architect Isamu Noguchi. The two met 90 years ago this year, in 1935. They were briefly lovers and then friends. The butterflies were, Noguchi said, something Kahlo could look at while she lay in bed with the pain she suffered from polio. These lines, pulled out of the center of Patti Smith’s poem, show what joy makes possible:

Within my sight

All pain dissolve

In another light

Transported thru

Time

By the butterfly

Symbolism, of course, makes me think about apricots, which I’ve come to see as a symbol of dignity and democracy. I think apricots can also help us find joy when we’re facing adversity. I’ll leave you, then, with this little joke that brought me a bit of joy when it popped unexpectedly into my head a couple of weeks ago! It brought me a good bit of sudden interior joy, and I hope it does the same for you.

Q: What do you call a group of dignity- and democracy-loving musicians that get together for an impromptu session?

A: An apricot jam!

Create a joyful future

Tag: ARI WEINZWEIG

Photographers, circles, Edgewalkers, and important new insights

One of the things I love most about the experience of regenerative studying is how other insightful people’s perspectives can help me to suddenly understand things I’ve been around for ages—and understand them in wholly different and intriguingly inspiring ways. It’s very much what Tomasz Trzebiatowski, photographer and editor of the terrific FRAMES magazine, wrote this week about the renowned Belgian photographer Harry Gruyaert. Gruyaert, who turned 84 in August, was a street photography pioneer half a century ago and a colleague of the remarkable Joel Meyerowitz, whose photographic work and writing have inspired me any number of times over the years. Writing about Gruyaert’s unique style, Trzebiatowski says:

Gruyaert’s work has always been thrilling in the way it articulates a particular way of seeing. He has had the good fortune to travel widely, and whether he’s taking images in Belgium or Morocco, London or Paris, airports or alleys, it’s not that he sees things differently. He emphasizes differently.

And this is, indeed, what happened to me in studying the work of another photographer who’s also a filmmaker, the Vietnamese American artist Tuan Andrew Nguyen. A single comment by Nyugen, a small part of a much longer conversation he had with Art21—the group that produces the PBS documentary series Art in the Twenty-First Century—offered me a wholly new framework with which to look at what makes our lives, organizations, and countries healthier, livelier, more creative, and ultimately more meaningful.

In the interview, Nguyen talked about his own life experiences, including the moving around the world he has done over the course of his nearly 50 years on the planet. He shared this thought that stopped me in my tracks:

I don’t think that being in between worlds is something that limits us. Learning to understand different worlds is going to be a skill that helps us to navigate a very precarious future. That liminality actually empowers people.

I had never considered the connection Tuan Andrew Nguyen made in that comment until I heard him say it. I’ve been turning it over and over in my mind, and, a week later, I agree. His statement makes total sense. My belated, Nyugen-inspired glimpse of the obvious, my interpretation of what I learned from him, is that as we look ahead to the second quarter of the 21st century we would be wise to work with this understanding front of mind:

People who regularly move through multiple worlds with a modicum of comfort and effectiveness have much higher odds of doing more and better work in the world.

Two months ago, I wrote a lot about the import of edge in organizational health. In that essay, I reminded myself and maybe you as well that the edges of an ecosystem—not any imagined hierarchical center—are where most new creative ideas, cool initiatives, and organizational innovations tend to come from. Which means, then, that the more edge we create in our companies and our communities, the healthier we are likely to be. Instead of pulling back from the edge, putting up walls around a theoretical center to “protect” us, we would be wise to shift the focus to creating more edges, and then spending a significant portion of our time in them. Edge work like this won’t always be fancy, but it can be exceptionally effective. Get out of the office, call customers, answer phones for a few hours, work the front door if you have one, riff freely on routines, read widely, engage enthusiastically on the periphery. To use a baseball metaphor, it’s useful to skip the skybox sometimes and sit, instead, out in the center-field bleachers, sipping beer from paper cups and squinting to see home plate—things look a lot different from the 23rd row in right-center field than they do from the front office.

This essay is, in a sense, a follow-up to that first one on edge. In the spirit of Harry Gruyaert’s good work, I’m taking something that I know well and emphasizing a different element of it. Spending time in and near the edges of organizations, philosophies, natural ecosystems, and more is awesome. But better still, as I now see thanks to Tuan Andrew Nyugen, is that taking things further, engaging with the edge, and then deciding to keep going into less familiar, or at times wholly unfamiliar, territory helps us enter a different world and often really wonderful new worlds.

Tuan Andrew Nyugen’s work is all about this approach to life. He is constantly moving between worlds and always doing it with grace, sensitivity, and skill. As the bio on his website states:

Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn’s practice explores the power of memory and its potential to act as a form of political resistance. … Through collaborative endeavors with various communities throughout the world, Nguyen sets out to cultivate and empower these strategies enacted and embodied by his collaborators.

Born in Saigon in 1976, Nyugen came to Oklahoma three years later with his parents and brother. From there, he went west to the University of California, Irvine, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in fine arts in 1999. He followed it five years later with an MFA at CalArts. A few months after that, he decided to move back to Vietnam, where he still lives now. He settled in Ho Chi Minh City, in part to reconnect with his roots. He also reconnected with his grandmother, a poet and writer, who passed away not that long ago at the age of 102. Nyugen’s work has always been about learning to create collaboratively, something we attempt to do here in the Zingerman’s Community of Businesses (ZCoB), too. We both believe that the more good people can weave into the creative circle, the better things will go at every level.

The fact that I gained this new insight about the import of moving regularly between worlds is evidence to offer in support of Nyugen’s belief. Tuan Andrew Nyugen is not a big name in the food business, nor has he written about leadership, anarchism, or any of the other subjects I engage with so regularly. Nyugen’s comments were shared from a country I know relatively little about, in a city I’ve never been to, in relation to a line of work that is way outside the realm of what I do every day. And yet, as you can tell, engaging with the new world of Tuan Andrew Nyugen got me thinking. And then writing. Journalist Kenn Sava says of Harry Gruyaert’s art, “His photographs will make you stop and wonder—what’s going on here?” And that’s pretty much what happened to me when I encountered Nguyen’s words about moving through multiple worlds.

Being able to understand and engage with multiple worlds, I’ve realized in reflecting on all of this, is a big part of what makes Zingerman’s what it is as we approach our 44th anniversary this winter. I can now see that even in those awkward early years after we opened the Deli in 1982, both Paul (for those who don’t know, my business partner since the beginning) and I were able to move from one world to the next and do reasonably well in any of them. I don’t mean that we couldn’t have done it better, or that we didn’t mess up many times, or that we don’t have a lot to learn. I just mean that from the get-go, we have each in our odd and awkward ways been reasonably adept at engaging with people from circles very different from our own. We relate fairly well to people of pretty much any age, race, religion, or walk of life. We have both, for as long as I can remember, been as comfortable talking to dishwashers as to department heads at the university. We happily work with bakers and busboys and also with bankers and big-time business leaders. We have both traveled a lot. We read a lot, and we go to a wide range of conferences. We move from one world to the next pretty regularly. It’s not uncommon for me to meet with someone who was just released from incarceration, and then move straight into spending time with some new business owners who are eager to understand how to incorporate. My passport doesn’t get stamped each time I do it, but the truth is that I’m crossing multiple borders almost every day.

Paul and I were, I can see in hindsight, what the team at ZingTrain would call “unconsciously competent”—we gave it little thought, and we were just good at doing it. Next time I talk about what makes us who we are at Zingerman’s, I’m going to tell the audience that this ability is embedded in the essence of the organization. Countless others here in the ZCoB are adept at doing it as well! And this ability to shift rather fluidly between worlds is now the norm for me and many of the people who work here.

Both Harry Gruyaert and Tuan Andrew Nyugen have traveled all over the world. Here at Zingerman’s, we do it a lot, too. We travel to study food, understand where our products are coming from, and, as in the case of Food Tours, for a living. That said, while movement between worlds may certainly include going to other countries and exposure to cultures of all sorts, a plane ticket is not a prerequisite for making it happen. We can enter new worlds without leaving our bedroom. Reading books about topics we don’t usually engage with is one way to do it. We also do it when we talk to people who have backgrounds that are wholly different from our own or beliefs that we may not share. It can be done, too, by experimenting in different areas of insight, or regenerative studying in specialties that are significantly different from our own. This is, I see now, what is coming out of my collaboration with Michael Dickman, which involves learning about poetry and how to put it to use in my everyday life. You can enter new worlds by taking classes in new-to-you fields of study, or, if you’re a city kid like me, by taking time to walk through local fields and pay close attention to what you find.

While I have embraced this new-to-me understanding, I know that moving fluidly and regularly between worlds is not the way much of the world wants to work these days. In fact, it’s the opposite of what seems to be happening around us in many settings right now. Far too many people are reacting to understandable bouts of discomfort by trying to minimize contact with other worlds. Historian Heather Cox Richardson wrote a whole column a couple days ago about how super-wealthy people are withdrawing from the world the rest of us inhabit today, and how a similar thing happened a hundred years ago during the Gilded Age. We have leaders who are working to wall off, to ban books, to forbid “foreign” philosophical frameworks, to remove people who don’t “look right,” “sound right,” or “write right.” All of this is happening, right now, right in front of us.

It seems that, out of understandable insecurity and anxiety, many people are living out something that my friend, the Irish writer Gareth Higgins, and his coauthor Brian McLaren have written about in The Seventh Story. As I wrote about a few years ago, the book is about the “seven stories” that are lived out regularly by human beings like you and me. The most rewarding option on their list is “the seventh story,” a story in which “love is the protagonist.” It’s certainly the story we are working hard to live in here in the ZCoB. Love is in our mission statement, our 2032 Vision, and our hearts. The authors also detail the six “other” common but destructive stories that dominate in many societies. Two stories that Gareth and Brian lay out in the book are what seems to be happening around us: The Isolation Story, where “we get away from them,” along with The Purification Story, where “we get rid of them.” Both stories reduce access to other worlds.

Nyugen’s theory is pretty much the exact opposite of isolation. When we seek to engage regularly with other worlds, we invite others in so they can experience our work and our world at Zingerman’s. And rather than getting away from others, we are regularly trying to spend time in their worlds to learn about what they do, as well as why and how they do it. This kind of positive work doesn’t have to cost a lot. It can be done quite effectively simply by spending time in different neighborhoods, studying an unfamiliar language at the local community college, reading books about philosophies that are wholly new to us.

Listening to TED Talks can be helpful, too. Fifteen years ago, the Turkish-British writer Elif Shafak, about whom I wrote a fair bit a few weeks ago, did a TED Talk in which she shared a good deal about her upbringing. Born in Strasbourg, France, her parents got divorced when she was still a young girl, and a young Shafak then moved to her mother’s homeland of Turkey. There she was raised by her mother and her maternal grandmother. Her mother, Şafak Atayman, was a westernized, modern Turkish woman. After graduating from college, she became a successful diplomat who worked for many years in the foreign service. By contrast, Shafak says, her grandmother was “more spiritual, less educated, and definitely less rational. This was a woman who read coffee grounds to see the future and melted lead into mysterious shapes to fend off the evil eye.” A young Elif watched as people came to her grandmother, who was not trained in modern medicine, to be healed of any number of ailments. Surprised by the effectiveness of grandmother’s seemingly very old-school healing work, Shafak asked her for the secret. Her grandmother’s suggestion was to “Beware of the power of circles.” As Shafak explains:

From her, I learned, amongst many other things, one very precious lesson—that if you want to destroy something in this life, be it an acne, a blemish or the human soul, all you need to do is to surround it with thick walls. It will dry up inside.

Now we all live in some kind of a social and cultural circle. We all do. … But if we have no connection whatsoever with the worlds beyond the one we take for granted, then we too run the risk of drying up inside.

Our imagination might shrink, our hearts might dwindle, and our humanness might wither if we stay for too long inside our cultural cocoons. Our friends, neighbors, colleagues, family—if all the people in our inner circle resemble us, it means we are surrounded with our mirror image.

Isolation—either individual or collective—is an idea that, to some, can sound good. I get it. I’m an introvert who regularly leans into having time alone, so I’m all for solitude. Used well, for reflection, regrounding, reading, and recharging, alone time can lead us to engagement with other worlds of knowledge, culture, and understanding. In other words, it can be conducive to connection rather than implicitly about isolation. But alone, on its own, will not likely get us where we want and need to go.

I mentioned the other week that Shafak calls our current era “The Age of Anxiety.” It’s an apt assignation. She also, though, refers to it as “The Age of Division.” The same walls that appear to protect also restrict. And as Shafak says, “It worries me immensely, seeing the walls rise higher and higher.” Walls limit access. They reduce the amount of edge, and they make it harder and harder to freely and fluidly move around any number of different “worlds.” As Shafak says:

Ironically, [living in] communities of the like-minded is one of the greatest dangers of today’s globalized world. And it’s happening everywhere, among liberals and conservatives, agnostics and believers, the rich and the poor, East and West alike. We tend to form clusters based on similarity, and then we produce stereotypes about other clusters of people.

Shafak cites the wisdom of Lebanese American poet Khalil Gibran, who said, “I learned silence from the talkative and tolerance from the intolerant and kindness from the unkind.” She transposes those lines into a learning for our present-day challenges:

From populist demagogues, we will learn the indispensability of democracy. And from isolationists, we will learn the need for global solidarity.

So, what do we need to do this “world-traveling” work? And how do we do it more effectively? Well, I’m just learning. Let me know what you think. Here’s my opening bid:

- An abundance of humility

- Dedication to dignity

- A generous spirit of generosity

- A worldview rooted in positive beliefs

- Consistently high levels of hope

- An endless cache of curiosity

- A healthy sense of self that allows us to learn, engage, and share without worry that we will lose ourselves in the process

People who don’t have these skills remain, of course, good people. But without these skills, it’s harder to engage outside our comfort zones effectively. Those who do have these attributes are far more likely to move freely to and from multiple worlds, learning well from each in the process. I’m talking about people like Harry Gruyaert, Tuan Andrew Nyugen, and Elif Shafak, people who move from one world to the next with regularity. They have learned how to take pain—which, of course, we all have in our own ways—and turn it into art that helps them heal and helps the rest of us lean into and learn from their creative expression. For example, one of Tuan Andrew Nyugen’s best-known works was a collaborative project entitled The Unburied Sounds of a Troubled Horizon that included turning spent U.S. Army artillery shells into beautiful hanging bells that make a symphony of lovely sounds.

In a metaphorical sense, that seems to be what the team at Emerge (which includes philosopher and chess Grandmaster Jonathan Rowson) is trying to do on a bigger scale: Take what has gone wrong in the world, learn from it, and combine it with what has long been right, to write about new approaches to the future. It’s an intriguing organization that seems to be involved in this work of moving through, into, and around multiple worlds, reflecting regularly on how to blend traditional wisdom with new insights and ideas. Of the present moment, they write:

We are at a fork in the road. Two kinds of possible futures for humanity are likely: further entropy and collapse, or the emergence of a higher-order system that is more complex and elegant than our current one.

It seems clear to me that the people Tuan Andrew Nyugen was talking about in the interview that sparked all this thinking—those who, like Nyugen, can move well between different worlds, those who learn well from others and who can embrace and engage with difference and diversity, all the while learning to be truer to themselves—will almost certainly fare well in the rest of the 21st century. They are the ones who can lead us towards Seventh Stories, and towards learning, dignity, humility, and more health for more people.

From the outside looking in, writer and speaker Judi Neal seems to be one of those people. Neal, who earned an advanced degree in organizational behavior at Yale University, has already given a name to people who walk in many worlds. She calls them—or us, I might be wiser to say—“Edgewalkers.” I love it. Neal explains:

I am passionate about organizations and teams understanding the value that Edgewalkers bring to the workplace. Usually people who have Edgewalker qualities are seen as strange and they are often marginalized. But Edgewalkers are the ones that see what others cannot see, and they have a commitment to making the world a better place. … We need our Edgewalkers more than ever in this uncertain and unpredictable world. The old ways of doing business no longer work, and Edgewalker leaders, and Edgewalker organizations can show us a new and better way.

Edgewalkers, to my sense of it, are the kind of people Tuan Andrew Nyugen was talking about. They spend a lot of time in and around the edges, and they regularly move past the edges and explore other worlds as well. With each metaphorical trip abroad, they add to their already wonderful wealth of knowledge. Over 10 or 20 or 30 years of practice, what an effective Edgewalker can enable is impressive. This description of Edgewalkers feels like a fair way to frame the work we do here in the ZCoB. It’s true, too, of many of the people I learn from and write about here in this enews. Elif Shafak, Tuan Andrew Nyugen, Little Mazarn, Pharoah Sanders, Sarah Harris from the band Dolly Creamer, adrienne maree brown, Harry Gruyaert, and so many others. Neal shares a quintet of critical characteristics that all Edgewalkers have in common:

- Self-awareness

- Passion

- Integrity

- Vision

- Playfulness

All five resonate with me. Neal also shares five skills that we can practice that help us to become more adept at walking the edges with excellence instead of anxiety. Again, I can relate to all of them, and they show up in the adaptive approaches each of us uses:

- Sensing the future. A healthy sense of where we’re going, per what Tuan Andrew Nyugen shared up top.

- Risk-taking. One example is Elif Shafak’s willingness to write about topics that are “taboo” in Turkey.

- Manifesting. To me, it sounds like what we call “visioning” here in the ZCoB.

- Focusing. The ability to actually implement learnings from the other worlds we have visited.

- Connecting. The decision to value others, to see their uniqueness, and to draw out the best in them.

Folklorist Henry Glassie, who led the Turkish Studies program at Indiana University, has spent his whole life engaging with different worlds. His work has taken him to Ireland, Turkey, Nigeria, the Appalachians, and Bangladesh for significant amounts of time. Insights abound in Glassie’s work, but this particular quote really caught my attention in the context of edges:

The creation of the future out of the past [is] a continuous process situated in the nothingness of the present, linking the vanished with the unknown, tradition is stopped, parceled, and codified by thinkers who fix upon this aspect or that in accord with their needs or preoccupations.

The ability to move fluidly from present to past to future and back again, over and over, is another way to effectively engage with different worlds. I realize we are actively teaching everyone in the ZCoB to do all three:

- The past by studying food, writing a lot about history, and staying committed to traditional food. This is not always what organizations do. Of her homeland, Turkey, Elif Shafak says, “Nations don’t always learn from history … If anything, we [Turks] are a society of collective amnesia.” The past, for those willing to use it though, can be a powerful tool for managing more effectively in the present moment. Tuan Andrew Nyugen says he “explores memory as a form of resistance and empowerment, emphasizing the power of storytelling as a means for healing, empathy and solidarity.”

- The present by teaching mindfulness and energy management, appreciating and cultivating great service, staying dedicated to finding joy, and actively looking for beauty. We work hard to help people learn to be in the moment.

- The future through our visioning work, which challenges us to regularly move our minds into the future. Tuan Andrew Nyugen’s short dystopian sci-fi film, A Dream Of The End At The End Of A Dream, uses an imagined future to send a message to us in the present moment.

This work of traveling regularly between worlds is, I can now see, a big part of what makes the books and music of my friends at Indigenous Resistance so compelling for me. They are all based on engaging with worlds and worldviews that most of us in the West would not otherwise know about. They are Edgewalkers extraordinaires. They share the histories of indigenous cultures in Africa, elucidate elegant insights from Ethiopian spiritual leaders, and visit Mongolian record shops. Through their records and books, they explore the writing of Native American activists, East African anarchists, and so much more. Each of their works makes clear what Tuan Andrew Nyugen knows—that it’s all about healthy connections with, dignity for, and active learning from other worlds.

Reading each of the Indigenous Resistance books has been a wonderful example of regenerative studying at its best. They have exposed me to an incredible array of new, always inspiring, often anarchist sources. They guide me from Uganda to Ulaanbaatar, Senegal to South Dakota, and everywhere in between. They introduce me to Jamaican musicians and Mongolian shamans, Native American poets and North African spiritual leaders, revolutionaries and writers, and so much more. They bring me into contact with a plethora of places and people I might likely never have known on my own. Their most recent print publication even has a photo of the ancient stone in Mongolia where the word “Turk”—now Elif Shafak’s homeland—was carved into writing for the first time.

This passage from Indigenous Resistance’s new book, Mongolian Dub Journey, seems to sum up much of this traveling-between-worlds work:

When one sees boundaries dissolving between ‘genres’ and art forms, this has always been very inspirational for me to observe. This is because I believe that is in these spaces of dissolved boundaries … where we can create the space to be truly creative and forge new pathways.

The people who move between worlds in this way, the Edgewalkers among us, are setting the positive, collaborative, and inclusive pace for the 21st century. It’s work we can all do. I smiled when I saw these words in a recent retrospective write-up about Harry Gruyaert’s work at the Helmond Museum in the Netherlands:

The origin of all his work is the world around us.

Look around. Listen. Breathe deep. Be ready. Other worlds, with a wealth of beauty and wisdom, await.

Explore other worlds

P.S. If you want to move through a whole range of different culinary worlds in a matter of hours, consider coming to one, or both for that matter, of the two “Best of 2025” tastings I’ll be doing at the Deli next month. The first one is Tuesday, December 2, at 6:30 pm, and the second one is the following Tuesday, December 9, at 6:30 pm. Hope to see you there!

Tag: ARI WEINZWEIG

Digging into any subject yields fascinating results

The amazing Austin-based band Little Mazarn, whose music I have loved for many years now, released a new EP, Election Results, last week. Like everything Little Mazarn has done over their decade of playing together, it’s poetic, poignant, touching, and, for me, exceptionally engaging. With Lindsey Verrill playing banjo and singing, Jeff Johnston performing on a remarkable electric saw, and, of late, Carolina Chauffe adding guitar and vocals, the band’s music sounds like no other. Here’s the backstory on the new release as Little Mazarn’s leader, Lindsey Verrill, tells it in the liner notes:

On November 5th and 6th, 2024, Little Mazarn had some studio time booked and went in to start a follow up album project to Mustang Island. It was a beautiful time of year, we had some fresh songs in the mix, and our friend Jolie Holland was in town. What could go wrong? Needless to say, things did not go according to plan. The heaviness of the American election results crashed through the studio door and landed right on top of us in our merry music making.

This EP is the result. After some tender listening, we decided these recordings needed to stand alone from a moment where things were very heavy, but we didn’t allow ourselves to be crushed. We made art, we were together, and we did manage to have some laughs. Now a year later, this message rings truer to me than ever. Though much has been taken, much abides.

We each, of course, have different ways of dealing with despair. Lindsey Verrill crafts lyrics, strums her banjo, and sings. I start studying.

For me, studying—whether it’s reading books, mindfully focusing my attention on a particular pattern over time, listening to talks online or in person, or spending time engaged in personal reflection via journaling—is, and always has been, central to the way I live my life. When I need a boost, I crack open a book. If I’m feeling down or confused, overwhelmed or out of sorts, 20 or 30 minutes of studying is almost certain to turn my mood around. Studying, I can see now, feeds both my mind and my spirit, and more often than not, it benefits our business at the same time. So, while many people think of studying as a burden they left behind when they finished school, I see it as a blessing that will be with me for the rest of my life.

I’ve never really framed it as such, but in recent weeks, I’ve begun to see that studying can be a regenerative process, a way to boost our own energy while putting ever-increasing amounts of good out into the world. I’m not talking about the kind of studying driven by grades or fear of failing that so many of us struggled through in school. I’m talking instead about studying as a way to get my own mind moving and to then actively share what I’ve learned with others in helpful ways. Studying that benefits me, the studier, and also the people and products that are part of our ecosystem. Studying that, rather than sapping energy through caffeine-fueled all-nighters, can now be framed as a fun activity to help with self-management, inspire new ideas, and give us the energy we need to stand up for what we believe in, even in the face of enormous pressure to fold our cards and retreat to a safe corner. The new Little Mazarn album is really a great example. The musicians took their despair and turned it into a different kind of election result, one we can listen to and learn from at the same time.

I am, by this point in my life, “intuitively” inclined to study, probably through years of neuroplastic shaping of my brain. Here’s a bit of evidence for the way studying is woven into my routines. It’s true to life and, in truth, a little hilarious.

I’m pretty sure it was about 10:30 this past Saturday morning when the penny fell out of my pocket and landed square in the center of the brushed suede of my Doc Marten sandals. My first thought was how cool the copper looked against the black of the shoe. My next thought, seconds later, was that I really knew next to nothing about pennies and probably would be wise to start studying them. Then I laughed out loud at my strangeness. With everything going on in the world around me and a long to-do list on my yellow legal pad, pennies were definitely not a top priority.

Most people, I’m fairly certain, would simply have picked up the penny, popped it back in their pocket, and gotten on with their day. I, though, am more than a bit odd. It used to make me feel estranged. Now it mostly just makes me smile and then get back to work. So, low priority as pennies were, I started looking up more about them about 20 minutes or so after the coin appeared atop my sandal. Within a matter of minutes, I was magically transported into the world of monetary history and the culture of coin-making. It didn’t take long for my mind to start spinning like a coin on its side—so many mental roads to go down for far more in-depth study. It turns out there’s a history major’s treasure trove of cool stories to tell about these little copper coins. Here are a few highlights of my brief foray into “pennyology”: