American Cheese Revolution

Wisconsin is probably best known around the world for its dairy. Though few people know it, back in the mid 1800s Wisconsin farmers were not thinking much about cows. Most farms had a cow or two, most cheese was made on the farm as a way to help feed the family. If you want the story in succinct headline form, check this one from the Milwaukee Sentinel 150 years ago (November 8, 1861 to be exact): “Wheat is king, and Wisconsin is the center of the Empire.”

Ed Janus tells the story more poetically in Creating Dairyland. “At first the pioneers came to make a home and a modest living from the land.” But, he adds, “then came the monoculture of King Wheat.” But, wheat would prove its own demise. The wheat crop collapsed only two decades after it began. Dairy, it turns out, is what saved the day.

The main engine of Wisconsin’s holistic development around dairy farming was actually an idea known as “Progressivism.” “Progressive reformers believed that livestock was to be the answer to the deficits created by wheat farming. Manure and grass would renew the soil, growing herds would create wealth for farmers, and investments in land, buildings, fences, and herds would restore the idea of building for the future.” Dairy farming and cheese making (over 80% of the state’s milk is made into cheese) saved Wisconsin.

By 1922 there were more than 2800 cheese plants in the state. But, of course, there are ups and downs in every story. Over the course of the 20th century although cheese production and sales continued to grow, Wisconsin moved from cutting edge to the middle of the market. Industrial giants like Kraft and Borden brought down prices but also made it harder for small farms and cheesemakers to survive. The drive for perfect cheese devolved into a drive for “defect free,” ever lower prices, and ever more consolidation into ever bigger cheese plants.

Times, happily, have changed. While so much of the country continued to slide downwards towards ever lower cost and commensurately low levels of quality, Wisconsin cheese is going in the opposite direction. The state that once toed the middle of the road has taken flight toward ever higher levels of cheese greatness. Wisconsin is, without a doubt, THE state that’s most supportive of its cheesemakers, that’s training and teaching far more than any other, and that’s generated more great new cheesemakers in the last twenty years than pretty much any other. Wisconsin may not be glamorous, but I think it’s the future of American cheese.

Dunbarton Blue—Delicious Blue Cheddar from Wisconsin

Chris Roelli is a fourth generation Wisconsin cheesemaker—his great grandfather came over from Switzerland early in the 20th century. After decades of cheese making at their plant in Shullsburg in southwestern Wisconsin, the family finally gave in to incessant pressure to lower prices and got out of the business. Chris, fortunately for the rest of us, never gave up hope of getting back into the game and he has in a BIG way. Dunbarton Blue is essentially a farmhouse cheddar with blue veining. Delicious, meaty, earthy, nutty, lots of bass notes and one of my favorites on our cheese counter right now.

Pleasant Ridge Reserve

This is a farmstead cheese made only from the milk of the herd at Uplands’ Cheese Company farm in the spring and summer months when the cows are out in the pasture grazing. It’s aged for over a year to bring out the flavor of the milk. And then to seal the deal, each year Uplands sends us samples of some of what they feel are the previous year’s best cheeses, and we get to choose the ones we want. Pleasant Ridge’s flavor is nutty for sure with a butteriness that I love, a close texture that you might find with a well aged mountain cheese, and a long finish.

Traditional Brick Cheese from Joe Widmer

A Wisconsin original developed in 1877 by a Swiss immigrant named John Jossi, this traditional cheese is truly pressed with bricks, hence the name. Unfortunately only a tiny percentage of what’s sold in the country as “brick cheese” comes from traditional production. For years, Joe Widmer was the only one left making the cheese. The bricks carry the bacteria that are so critical to developing the full flavor of the cheese. Great with beer, great on a sandwich, or maybe with a spicy Gewürztraminer wine, brick is a winner in my book.

Liederkranz

Like Limburger and Brick, the Liederkranz comes from the washed-rind family. It’s a bit lighter in texture and a touch mellower in flavor than the other two. The story of Liederkranz goes back to 1891 to another Swiss immigrant, Emil Frey, living in upstate New York. He named it after the local singing society. In the 1920s, Liederkranz production moved to Van Wert, Ohio and it was made there until the 1980s. In 1985, the “last” Liederkranz was produced. For years, we had customers coming to the Deli still loyal to their long-time favorite cheese. The story took a happy turn when Myron Olson and crew at Chalet Cheese revived the recipe in Monroe, Wisconsin. So, celebrate the return of Liederkranz! My favorite way to eat it is simple—just spread some of this delicious soft ripened cheese on a slice of caraway rye from the Bakehouse.

Farmstead Marieke Gouda

Marieke Penterman and her husband Rolf arrived a few years ago from the Netherlands, coming over in the hope that they’d have an easier time finding land on which they could farm and then, eventually, make cheese with the milk. The couple, their five young kids, and their herd of cows all come together to make what I feel like now is one of the most flavorful young cheeses I’ve tasted in a long time. Buttery, soft, a touch of vanilla, complex, Marieke Gouda is mellow enough to be popular with people who are a bit anxious about eating artisan cheese but equally well accepted with those who’ve traveled the cheese world extensively. I love it the Dutch way—for breakfast with a bit of rye or pumpernickel, some good butter and a strong cup of black coffee.

Rush Creek Reserve

A recent, and very excellent, offering from Andy Hatch and Mike Gingrich at Uplands Cheese this one is much softer and even more seasonal than Pleasant Ridge. It’s made in the style of a Vacherin Mont d’Or which will likely raise high excitement amongst those who know and love fine French and Swiss cheeses. Rush Creek is made only in the fall when the milk is particularly rich and very delicious. It’s a washed-rind cheese with a thin, slightly sticky rind, wrapped in a wood band and aged for about 8 weeks so that it’s nice and creamy inside. In the winter I really like to eat it atop just cooked potatoes, and we should still be able to find some good, locally grown ones out there to steam up. Cook the potatoes ‘til they’re really tender, then crack ‘em open. Drop on a bit of butter, some sea salt and then spoon on the Rush Creek. I leave the rind behind—just spoon out the creamy center of the cheese.

Wisconsin Mountain Cheese

Available ONLY at Zingerman’s Roadhouse and Creamery

Made by the Jaeckle family who moved their cheese making from Switzerland to the States years ago, this has long been one of my favorites. Basically it’s a Gruyere recipe, made as per Swiss tradition in old style copper kettles. But because it’s done in smaller sizes with Wisconsin milk, water and bacteria, it’s got a flavor all its own. Anyone who loves good mountain cheeses will go for this one in a big way.

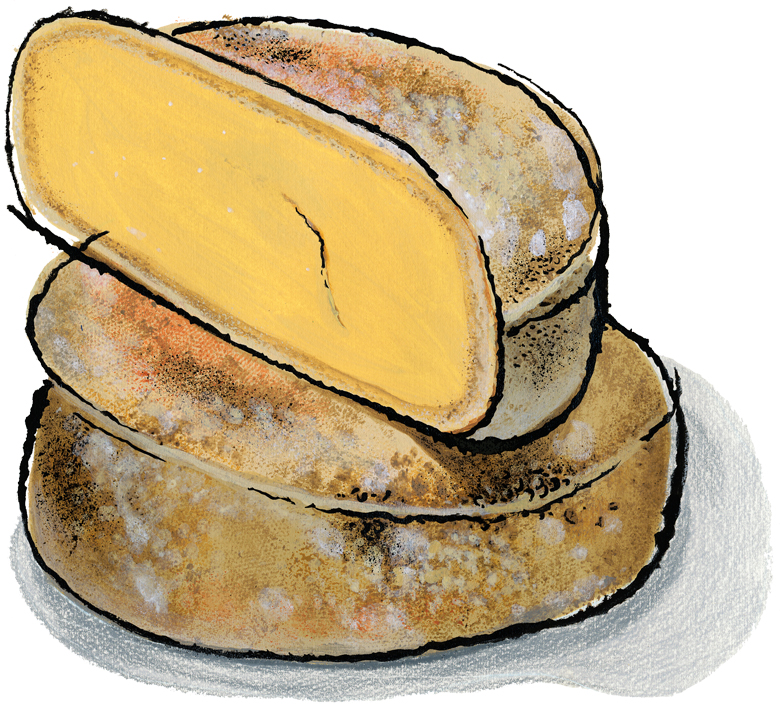

Willi Lehner’s Clothwrapped Farmhouse Cheddar

If you travel to the small town of Blue Mounds, you might have a shot at seeing—and then tasting—one of the best farmhouse cheddars in the country. Alternatively you can also catch Willi Lehner at the Saturday morning farmer’s market in Madison. Willi actually grew up in the trade—his father emigrated from Switzerland and began making cheese in Wisconsin, which is where Willi was born. While there is, of course, no such thing as perfection, he’s getting pretty darned close with his cloth-wrapped, cave-aged cheddars. Full, rich, earthy, nutty, flavor, with a touch of egginess and all the mystery and magic that mark the great English cheddars.

Finnish Bread Cheese

The Finnish name for this cheese is Juustoleipa (pronounced “you-po-stay-LAH”) but it’s a whole heck of a lot easier to just call it Finnish Bread Cheese. In Finland the cheese is made from reindeer or goat milk as well as cow’s. Curd was set and then dried to preserve it. To prepare the dried cheese it was often toasted over an open fire, which is, in fact, one of the best ways to eat this modern day, made-in-Wisconsin version as well. It’s also very good fried up and served on salads, or with any sort of berry preserves.

Zingerman’s Art for Sale