Zingerman’s Spiced Pecans

An annual holiday classic handcrafted across the ZCoB I can’t remember when we first started making spiced pecans a holiday treat. What I do know for sure though is that over the years, they’ve become a Zingerman’s classic—people start asking me in August when they’ll be available. In our never-ending effort to always improve what […]

Read more »

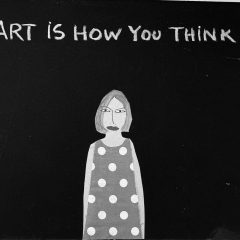

Zingerman’s Art for Sale