Burgers’ Smokehouse, a Family Business Built on Country Hams: An Interview with Steven Burger

Steven Burger with some country hams. (All photos courtesy of Burgers’ Smokehouse

Based in Missouri, Burgers’ Smokehouse is a four-generations-deep family business that’s been specializing in pork since 1952 (that’s the official date, but the family’s patriarch E.M. Burger, a farmer, began selling hams on the side in the 1920s). You might have read about the company in Zingerman’s Guide to Better Bacon, where Ari professed a fondness for Burgers’ old-style country hams, which are dry-cured with salt, black pepper and brown sugar and smoked over hickory wood for about 12 hours. Steven Burger, the company’s president, was kind enough to speak with us about his company’s legacy, and he’s also flying all the way here to speak at Camp Bacon’s Main Event and Bacon Ball. Don’t miss your chance to meet him and his hickory-smoked bacon!

Zingerman’s: Why did your grandfather go from farming to producing country ham?

The Ham House was constructed in 1952

Steven Burger: Well, actually, my grandfather was curing hams much like many farmers in this area were back at that time. Curing country ham was much like putting out a garden—it was just a way of life, a way of having a food supply in rural Missouri back before refrigeration. Really, the country ham business, as a commercial enterprise, really gradually emerged over many many years. From the mid-20s to the early 50s, he was curing hams on the farm. As people moved off the farm into the bigger towns around Central Missouri, he gained a reputation for doing a good job curing country ham, so he would have people asking about buying hams. He realized he could make more money curing and selling ham than he could out of the whole hog, so that became the economic motivation for continuing. Then in 1952, the business had surpassed what he could cure in the farm buildings, and that’s when he built our ham house. That became the nucleus of the modern country ham business—that first building is still part of the plant here, but the rest of the plant has kind of grown around it.

Z: Do you still cure hams in the ham house?

SB: No, but it is our operations office. It’s certainly has a very important purpose, but it’s essentially the operations office for managing the rest of the plant. We retained one of the original walls that we didn’t cover with anything else expect a fresh coat of paint. It’s the original 1952 wall.

Z: Your grandfather learned curing from his mother, who was German, so this was a tradition that was passed down in your family.

SB: It essentially came through our German ancestry. The curing techniques that came from my great grandparents that came from Germany and settled in the late 1800s.

Z: You’re the third generation. Why has it been important for you to stay in the family business?

SB: I came out of college in the mid 1980s, and at the time, the business was a good deal smaller than it is now, but I was raised in the company and spent many summers and Christmas holiday breaks working in the company, so it was something I was very familiar with. When I graduated in college and got out, it was just a natural progression to come right on home and begin working in the company.

Z: Why has maintaining the older food traditions of producing country hams continued to be important to you?

SB: Well, maintaining high-quality, niche markets is kind of a fun end of the business to be in because much of the success of our company is on telling our story, and a lot of that has to do with rich tradition with roots that go back to Europe and carrying forward curing techniques that have really been around for thousands of years. Being able to continue that story here in the United States is certainly a fulfilling part of the business to be in.

Z: You’re the third generation, is there a fourth generation coming into the business?

SB: Well, we now have rules for coming into the family business that requires outside work experience. Every generation has to build sets of rules that are appropriate to that generation in order to continue keeping the company in the family. We felt it was important a generation ago, after our generation came in, that the numbers were going to get big enough in the next generation that if the company gets bigger—which it has—and more complicated, then it’s really going to benefit our family and the business to get more outside experience before even being eligible to come in. The four [members of the fourth generation] that are here have met their educational and work requirements and have come in and currently playing very valuable roles in the company.

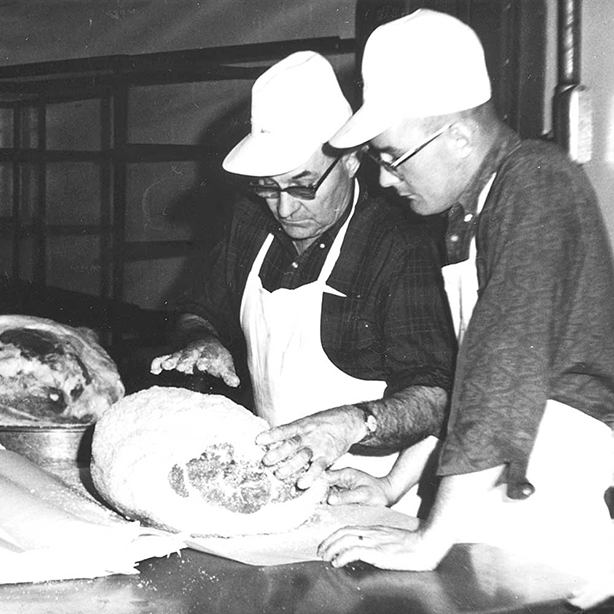

That’s the founder of Burgers’ Smokehouse, Steven’s grandfather, E.M. Burger on the left

Z: What’s the difference between dry curing and wet curing?

SB: There are two basic curing methodologies. One is the moist-curing, which in moist-cured products, you suspend the cure and the seasonings in a liquid form and inject the cure into the ham or meat product. Much of what you see in the stores today is some form of injected product. It produces a ham that’s going to be sweeter, moister, much more mild in flavor. On the other side of that is dry curing, and here, the seasonings are applied to the surface of the meat in a granular form and the dry mixture mixes with the natural fluids of the meat product and absorbs in the muscle tissue naturally, rather than being injected through mechanical processes. This process, which was initially done because it was necessary to preserve meat before refrigeration, continues now for the unique flavors, the complexities of the flavors that you get through the natural process. Not unlike cheese, wine, and other processes that create high-end, unique flavor experiences. In Europe, you have dry-cured hams that are, for the most part, consumed raw, sliced paper thin. You’ve got serranos, black forest, and west valley and the prosciutto that come out of the dry cured side of curing in Europe, and when those processes were brought to the United States, it became known as country ham. Here in the United States, those hams, rather than being aged long enough to be consumed raw, would get cured and preserved and then would be consumed early enough in the curing step that it became common to either fry or bake hams here in the United States. That’s how you see country ham consumed here?

Z: How do you like it best?

SB: I eat both, but I’m partial to the country ham. Particularly to the older country ham that have the deeper color development—as the ham ages, it goes from a more pinkish color to a darker, more of a burgundy look. With that, you have a higher salt content, a little drier textures, but the flavor development of a ham is also heightened.

Z: How long do the country hams cure?

SB: The hams that we cure for mass commercial markets are about three-and-a-half to four months. You start getting into the higher end hams around seven or eight months on up to a couple of years, depending on a lot of factors. You’ve got quite a few country ham producers out there that fill a boutique niche, where they’re carrying heritage pork and aging for very long periods of time and marketing those through mail or high-end restaurants, that sort of thing.

Z: Is country ham your biggest seller?

SB: In our company, country ham is about half of our business. The other half is just a wide variety of other cured, smoked meat products, but country ham is still very critical to the success of the company.

Z: What are some of your favorites of your other cured, smoked meats?

SB: Oh gosh! Country bacon—you just can beat dry-cured bacon. And there’s a lot of neat things we’re doing with bacon today. We just began producing a pecan-smoked bacon. We already have an applewood-smoked bacon, pepper-coated bacon, maple and cajun. We have them available in different slice thickness for different applications for both food service and retail. A really neat item is the country jowl.

Z: Why is the jowl so special?

SB: I eat more bacon, but the jowl is just something that most people don’t eat as routinely as they do bacon. But, it’s every bit as good. The fat is a creamier fat, and it’s just a nice alternative to bacon from time to time.

Z: Last question: Why is the apostrophe at the end of Burgers’ Smokehouse? Why not Burger’s Smokehouse?

SB: That was because of my grandfather. He only went to school through the eighth grade, but his understanding of English was if he put the apostrophe before the s that meant it was his smokehouse, exclusively. But putting the apostrophe after the s, it was inclusive, and so it’s Burgers’ Smokehouse, meaning it’s all of the family’s. It was his way of saying it wasn’t only his smokehouse but was the whole family’s. Whether that’s totally grammatically correct is beside the point, he wanted to make sure that he communicated it was the entire family’s that was involved and not just him.

Zingerman’s Art for Sale