The Impact of Art and Artfulness in Life & Business, Part 1

This interview with Ari Weinzweig, the co-founding partner of Zingerman’s Community of Businesses appears in the March-April 2018 issue of the Zingerman’s Newsletter. You can pick up your copy at any Zingerman’s business or read it online. Read Part 2 of this interview right here.

ZINGERMAN’S NEWS: Do you remember the moment you started thinking about this whole idea of living life as an artist?

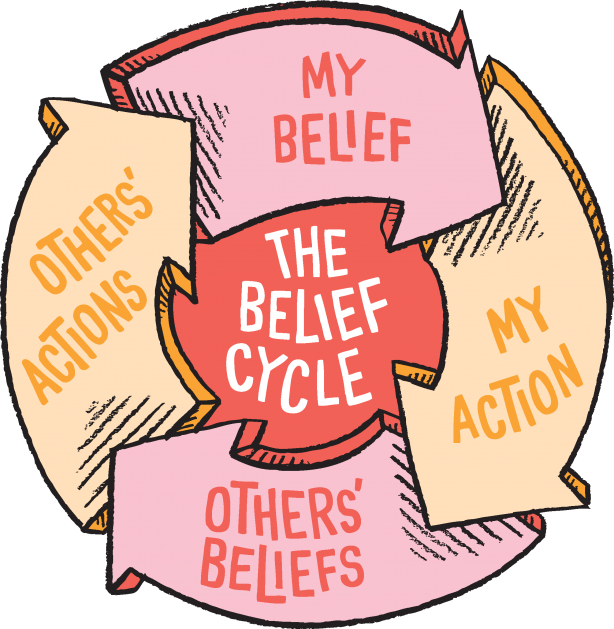

ARI: I do actually. I’d been working on The Power of Beliefs book for quite a while. The whole book is built around the self-fulfilling belief cycle that I’d learned from Bob Wright of the Wright Institute in Chicago. The cycle got me thinking in new ways and I haven’t stopped thinking about it since. That little diagram turned into a 600-page tome. It talks about how our beliefs lead us to take actions—every action we take is based on what we believe. In turn, those around us form beliefs based on our actions; their beliefs in turn lead them to act accordingly. And their actions, it turns out, most often reinforce our original beliefs. This cycle, I’ve come to realize, is playing itself out in our lives, all day, every day.

THREE OF MY BIGGEST TAKEAWAYS FROM IT ARE:

What we believe has an enormous impact on how we act and how our lives are—in essence, our beliefs are creating a lot of our reality. As William James said, “Belief creates the actual fact.”

What we believe alters what we see and experience—we tend to filter out information that doesn’t fit what we believe, and we allow in the information that supports the beliefs we already hold.

Because beliefs are not genetic, we can choose the beliefs that are most likely to get us to the outcomes and lives and businesses we’re trying to create.

I’d long had this idea of approaching business and life as if they were art. As I was playing around with early drafts of the Epilogue, it dawned on me that because of these key concepts of the belief cycle I just outlined, that artists—in my mind at least— would seem to experience life differently from others.

First, it would be in what they see, hear, feel, smell, or taste. Norwegian psychologist and artist Stine Vogt found in her studies that artists see more of the whole picture, whereas non-artists tend to focus mostly on the main themes. Artists, she found, are more aware of what’s not in the mainstream of our minds. They view the small details that others often ignore more holistically, as part of the bigger picture rather than just focusing on what’s in the foreground. I started to realize that wasn’t really about natural talent—it was something they’d figured out, or had been taught. Often it was really early in their lives, but sometimes as adults. Artist Paul Foxton said, “The kind of seeing we [artists] employ is learned. It’s at least partly—possibly mostly—that we habitually focus our attention more on what we see, and partly because we’re actively looking for different things.” I know from my own experience in food that folks in our industry taste and smell much more attentively than others are likely to. And I imagine it’s the same for poets with words, and musicians with sounds.

Secondly, I started to believe that artists would then be committing more attention to the way the raw material that they’ve “taken in” are put together. They’re more mindful about what they do, how they design things. It’s easier said than done, but it’s definitely doable. Things that seem mundane to most become special and significant to the artist.

To be clear, I’m not saying that everyone needs to be a painter or a poet or play guitar. It’s really a different way of being in and viewing the world. Writer Julie Cameron calls it “the artist’s way.” Painter, teacher, and author Robert Henri calls it “the art spirit.” Painter Patrick Earl Barnes says, “Art is how you think.” I love what all of them have to say and I love their work. However you want to frame it—or phrase it—it struck me that if life and business are art, then what we do and what we design are likely to be more creative and more inspiring if we actually imagine ourselves as artists. We place and position things more mindfully, we’re more conscious of what we say and do, we notice the small details, and we pay a lot more attention to tiny bits of beauty that are easily missed by others. So, I had the thought then to suggest that we might all want to imagine ourselves as artists (of whatever sort struck our fancy). And there you go!

ZN: Do you think that an artist would approach life differently?

A: Well that’s a generalization but I do believe that a great artist is paying more attention. I mean, that’s true for all of us, really—we all tend to pay more attention to the areas of the world that matter more to us.

So, if you believe you’re a good parent, you take in a lot more information about parenting than, say, I do since I don’t have any kids.

If you’re a basketball player you’re paying more attention to the nuances and details of a basketball game than a fan will see. And, of course, for artists, the nuances and details of the world all provide raw material for their craft. So, visual artists, as one example, tend to notice colors and shadows, and shading and texture much more than the rest of us. Musicians listen to sound much more mindfully. Writers take in all sorts of details because they provide material to use in essays and articles (at least, I do).

Poets choose their words with great care. I love what Robert Henri wrote, “It is harder to see than it is to express…A genius is one who can see.” It’s my belief that there’s genius and a jewel-like spirit inside every single person you or I will ever meet.

And then the second thing is that they’re much more careful, mindful, conscious of what they do with all that. And it struck me that those seemingly small changes would—and do—add up to a much more rewarding existence. The main point is that it’s really about a way of life, not a particular skill set like painting. It’s what Enrique Celaya Martinez said: “Being an artist is not a posture or a profession, but a way of being in the world and in relation to yourself. An artist is revealed in his or her choices.” I agree.

ZN: What’s the alternative?

A: A lot of us are unknowingly raised to live what writer and psychologist Ellen Langer calls “mindlessly.” She says it’s the opposite of mindfulness. And, she says that a large part of the world goes through its routines without giving a whole lot of thought to them other than doing them well enough to get by. I know I’ve done it at various times—too long sometimes—in my life. It’s easy to do—we just zone out and get done what we need to get done. We go through the motions. It’s just that we miss a lot of the beauty and we lose our ability to piece things together with meaning and elegance.

I was writing, playing around on the page, and all that came together. I realized that being a great artist—at least in the area of one’s life focus—is the opposite. It’s about being mindful. Conscious. Attentive to and appreciative of the detail and nuance. You can plug in poets or musicians or sculptors if you want. Or carpenters working with wood or potters throwing clay. Or artisan cheesemakers or master bakers. The idea is the same—if each of us approached our lives as artisans crafting something special, something that expressed who we wanted to be in the world, then I’m pretty sure we would pay more attention. Attention to the eyes of the person we’re talking to. To the energy of the people we work with. To the flavors and textures of our food. To the laugh of someone we love.

Great artists take them in, file them, put them back out in consciously chosen ways. And all that struck me as a much more interesting, and much more rewarding way to live. And to work.

There’s a tendency in the press and in common conversation to focus on the people at the “top.” It’s the idea that only the “great leaders,” the “great musicians,” etc. have real value. That those people might be “artists” but the rest of us are just implementers. I’ve always looked at it the other way around. Those “great leaders” are surely bringing their creativity to the fore in their work and inspiring others. But I really believe that everyone can be a great leader and that, in the right mediums—i.e., the way they live their lives—everyone can be a great artist. In business, in life, in anything they’re really interested in doing well. While we may not have the physical ability to paint like Picasso, write poetry like Marge Piercy, or make music like whatever musician whose work you really love, we all have the ability to design a beautiful day. To imagine and enact a caring interaction with someone we know. To write a moving and touching note of appreciation.

Now to be clear, some of us have access to more means than others. If you have Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs” in mind, then it’s clear that people who are struggling to survive may have less immediate bandwidth for this than others who may have more money, more tools, more support, etc. I think we all know that too many people in society are under enormous pressure to just pay their rent or put food on their tables. When you’re worried about finding a winter coat for your kid, or when you’re stressing about how to buy food for breakfast in the morning, it’s a lot harder to put energy into imagining interesting details. But still, even with the pressures of society, the challenges of getting through day to day life without a lot of means, there are ways to design small positive pieces into our lives. As Hungarian Holocaust survivor and psychologist Edith Eva Eger says, “Things aren’t important, but beauty is.” Even in the dark moments and stressful stretches of our lives, there’s art to be found. As Eger explains, “Our painful experiences aren’t a liability—they’re a gift. They give us perspective and meaning, an opportunity to find our unique purpose and our strength.”

ZN: So how would this play out in the workplace?

A: Well, when we start to notice the nuances, then the small things matter much more. We start to see the beauty in little things. I know for me that it continually pushes me to be more attentive. To catch myself more quickly when I start to slide into “mindless” behavior. I still slip, of course. Thinking this way, though, has helped me to catch myself much more quickly. Anyone can do it. And it does make a difference. Imagine if instead of approaching meetings as if they were some dull drudgery that we needed to deal with, we imagined them as improv skits in which we were actors? Or tryouts for an acting troupe we hoped to be chosen for. Or material for a play we were writing. It just seems like approaching things creatively like that makes life a lot more fun and more interesting. At least it does for me.

It’s also important because when we’re working mindlessly, we’re not using our creative abilities to tackle problems or innovate with new approaches. When we’re going through the day mindlessly we’re more likely to be insensitive to the struggles of co-workers or customers. All of which are creating more work, leading us to miss opportunities, increasing costs unnecessarily, etc.

If you imagine the difference between 50 people in a business who are mindfully, carefully, and caringly attending to nearly every action they take and treating each moment as if it matters in making the work of art that is their day, and compare that to a company with 50 people who are just going through the motions…that’s a pretty significant difference.

ZN: Then there’s the art you make at Zingerman’s?

A: I was just thinking about that. We have a small team of full-time designers, illustrators, sign makers on staff. They do all of the newsletters, catalogs, websites, posters. Plus more folks who have other roles for their main work here but double by doing beautiful drawings or chalkboards or writing copy.

We actually sell the posters—they’re beautiful works of original commercial art. All of those illustrations that people see in our mail order catalog and on our websites are done here in-house. Also, the beautiful scratchboard drawings that are in the business books. Packaging, too—check out the coffee bags, bread bags, candy bars and gift boxes. It’s pretty amazing to be surrounded by all this original art every day. There’s a lot of creative writing work, as well. Frank and Amy (Managing Partners at the Bakehouse) just put out the Zingerman’s Bakehouse cookbook last year and it’s winning raves all over the place. Maggie (managing partner at ZingTrain) is working on a book as well. All the writing for the catalogs and the websites. About five years ago we started a Zingerman’s writing group that runs twice a year. It’s led by Deborah Bayer who taught me a ton about writing and who edits a lot of the work in the Guide to Good Leading books.

And then, of course, there’s all the food! Pretty much everything we make here is an artisan product. Bread and pastry at the Bakehouse, cheese and gelato at the Creamery. Candy-making, cooking, coffee roasting. They all, when done at this level, create acts and effective expressions of the spirit and beliefs of those who make them. Really, I guess, as I think about it, we’re kind of surrounded by it! Which is a nice thing!

ZN: Where did you get the idea of thinking about business as art?

A: Probably 25 years or so ago. Maybe more, even. It dawned on me that designing our organization well was as much a creative act as the work I was doing with food and cooking.

Before that realization, in the context of the new book, I’d say I had negative beliefs about a lot of the organizational work that we needed to do. I’d seen it as drudgery, or a problem I “had” to deal with. But when I started thinking of it as a creative act, the whole thing got a lot more interesting and a lot more rewarding. I started to realize that, just like a beautifully designed building looks better, works better, and feels better, most of the people using it can’t tell you what it is that makes it feel that way. Same with a great organization. It feels better and works better even though most people may not be able to tell you why it works as it does.

Today, having come to think of things much more in alignment with nature, I’d use the metaphor of a beautifully designed garden. It looks great. It’s comfortable. But it’s not just about surface-level beauty. It actually works better—more sustainably, enriching the soil, retaining water effectively, etc. And although one can walk through it and casually appreciate it in a few minutes, it takes a LOT of hard work, advance thought, skill, creativity, and care to make it what it is.

ZN: It seems like a lot of this is about relationships?

A: Yep. Joanne Leonard, the Ann Arbor-based artist told me, “I’m interested in what could be called rhythms and rhymes—a diagonal here with another, similar one there, or a dark shadow off-set in another place, by a light but similar shape.” I agree. I think I look for those rhythms and rhymes in the way our spaces are laid out, in the way an organization relates to the community it’s a part of, etc.

It’s a lot about your relationship with yourself as well. It’s only when we really get to know ourselves, when we can (more often than not, at least) separate the voices of all the other people we know and care about that we’ve internalized from our own…that we can sort through things to get where we want to go. I like the Robert Henri line: “There is nothing more entertaining than to have a frank talk with yourself. Few do it—frankly. Educating yourself is getting acquainted with yourself.”

ZN: Part of this focus on business as art seems to be played out in your focus on uniqueness.

A: That’s true. It’s just a lot of what’s always appealed to me and motivated me for as long as I can remember. It was true when I was a kid. It was true when I was in school at Michigan—that’s a lot of what was so intriguing to me studying the anarchists. They were all about honoring every person as a unique individual. Which was so much the opposite of people being swallowed by society and pressured to fit in and conform. I love the Rollo May quote about “the opposite of courage isn’t cowardice, it’s conformity.” But of course, walking one’s own path is much easier said than done!

This is a lot about what resonates for me with this art-life-spirit approach. I really like the John O’Donahue line: “The poet wants to drink from the well of origin; to write the poem that has not yet been written.” With businesses, the sort of mass market, big box franchises that are plopped down or opened up all over the country—actually all over the world—are the opposite of uniqueness. They’re pretty much identical whether you go to the south side of Ann Arbor or South Carolina. Wendell Berry wrote that this conformity is, “placed upon whatever landscape merely by imposition, as a cookie cutter is imposed upon dough.” Less obvious, there are so many businesses that are trying to catch the latest wave, to take advantage of the trends, to take on what everyone else is doing, to follow the market leaders as quickly as possible. That’s not a terrible thing. But I don’t think it makes for optimally interesting businesses.

Maybe a better word is originality. Because in a way we’re all just combining things that already exist in some other spot or form, or putting our own spin on something that’s been done for centuries. The cool thing, I think, is that when we’re true to our spirit and to who we really are, then what comes out is, by definition, going to be original. I love Robert Henri’s quote—“Don’t worry about your originality. You couldn’t get rid of it even if you wanted to.”

So often, though, people are watching others’ success patterns and trying to tag onto their success. Which isn’t evil, but it’s not all that interesting. I was reading an interview with Scott Belsky in Tim Ferriss’ book Tools of Titans. He said, “It’s easy to see why most investors rely on pattern recognition. It starts with a successful company that surprises everyone with a new model…what follows is endless analysis and the mass adoption of a playbook that has already been played…sure, [those companies] may create a successful derivative, but they won’t change the world. If you only look for patterns from the past, you won’t venture far.”

I’m convinced that everyone we work with has it in them. Like Henri said, “Art, when really understood, is the province of every human being.” There’s a musician named Lauren O’Connell whose music I really love. When I was watching some YouTube videos of her playing one day I discovered that on many of her recorded songs she actually plays nearly all the instruments herself. That was impressive. But what blew my mind was that how many everyday ordinary things she turned into instruments. Everything from loose coins shaken on a tennis racket and then tapped with a spoon, to rubbing her finger on the edge of variously filled water glasses, tapping glasses with a blue ballpoint pen, hitting a phone book with a drum stick, to using a bow to play the banjo. She stomps her boots on one song to start the percussion. While I’m sure she’s not the first person in the world to do those things, she’s clearly put them together in a way that brings something special to her music and performance. And it’s not just an oddity or affectation. She uses it to make really great music.

The opposite of originality is standardization. It’s the industrial model. On a personal level, it’s—to a greater or lesser degree— dehumanization. Where individuals don’t matter. At the extreme level that can be enslavement, concentration camps, lynchings, pogroms, etc. But on a far less extreme, much more common, middle of the road level, it can just come in the form of people being treated like statistics or machine parts. Like they’re unimportant, not creative, not capable. Like they have no value. They get put into boxes. They’re assigned identities based on…you name it—who they hang out with, the color of their skin, what they study, where they worship. It’s true with people and it’s true with big box stores set down at the crossroads of beautiful backcountry. If you do what everyone else is already doing, then the only draws you really have are price or location. Both of which are relatively easily overcome for someone who wants to compete with you.

I’m always inclined to go the other way. To try to do things that honor the individual for who they are and that try to create businesses that are doing something unique and special. Part 1 of the Guide to Good Leading Series has much more on this.

ZN: And how does this translate into business?

A: I believe ever more strongly that great businesses are unique in the way they put themselves together and the way they put themselves out there in the world. Great art is always a reflection of the soul and spirit of the person who makes it. I love that line from Thelonius Monk about a “genius is the one most like himself.” I agree. And I think it’s true of organizations. Great businesses are the ones that are “most like themselves.”

Of course, it’s harder to really be ourselves than it is to know that it’s a good idea to be ourselves. But that’s really what this whole idea is about. Creating something special that’s an accurate and effective manifestation of the spirit, values, beliefs and passions of the person or people behind the project. An artful existence—whether personally or collectively—that makes a positive impression on the people who are around it. And, personally, I’d add that, at least for me, it had a positive impact on the people and place that it comes into contact with. But that’s another interview.

ZN: How did that work out for you guys with Zingerman’s?

A: For me and Paul, all of this was implicit—granted in rough form—in what we were trying to do from the get go. From the beginning of the Deli back in 1982 I was always focused on creating something special and unique. Not just a copy of a deli in New York or Chicago or Detroit. It just seemed more interesting to me to work on. And, I believe very strongly, ultimately a better business. Because, while it’s almost always easier to sell people what they’re already used to buying from others, in the long run you really don’t have anything uniquely your own to offer when that’s what you do.

On the other hand, the businesses that do something special, that create a unique model, that put pieces together in unique ways have a much better shot at doing something memorable in the marketplace. So customers are drawn to them. People who like creative work want to work in them or with them. The press wants to write about them. And that’s what I wanted to create.

The same effort to create uniqueness was built into the vision for Zingerman’s 2009 that Paul and I wrote in 1994. Rather than follow the standard “open more stores” model, our vision was designed to create growth by recreating uniqueness. So, we designed a business model in which each business would be part of the Zingerman’s Community, but, at the same time, each would have its own specialty.

Each would have a managing partner, or partners, in it—in this sense, they’re the artist whose inspiration informs that business. Our hope was that we kept the same energy of uniqueness that had helped make the Deli so special. In many ways, it’s harder to walk one’s own path. I’m with Herman Melville— ”It is better to fail in originality than to succeed in imitation.” You know, it’s the old Frank Sinatra hit—“I Did It My Way!”

ZN: So you don’t think that the standard business model of opening more units of your successful original is “art?”

A: Well, I think it’s “art.” It’s just not great art. Or not the kind of art I’m interested in. I always say to people: if you think there’s really no difference between a business with a single unique entity and one that replicates itself over and over, then why is a Picasso original worth millions when a Picasso print is worth next to nothing? The art is technically the same. But the feel, the energy, the nuance, the details, the uniqueness – totally different in the one he actually painted! I mean, I love Apple products and I admire a lot of what they’ve done. And I think the idea of the Apple store was very cool. The first one they opened blew people’s minds. But when I walk through mall to get to the Apple store in Ann Arbor and the store is 90% the same as every other Apple store in the world, it’s not all that exciting. I go there because I need to get something and really that’s it.

The same is true with being a market leader in anything, rather than a follower. When we’re following in someone else’s wake rather than creating our own path, the second and third and fourth players in will always be compared—almost always unfavorably—to the original. I’ve generally always tried to do the opposite—to go away from the trends where I can.

I love that Robert Henri quote: “The individual says, ‘My crowd doesn’t run that way.’ I say, don’t run with crowds.” Running with the crowd is often easier in the short term and it can definitely make you more money more quickly, but the businesses who follow in others’ footsteps are never regarded as innovative artists in their field. Jack Trout wrote about that phenomenon years ago in his books on market positioning. If you’re in a field in which someone else is already the pioneer, you’re stuck with, at best, second place. I stand by the statement from the Positive Organizational Scholarship folks here at U of M that says, “Excellence is a function of uniqueness.” The more you do something in a way that others haven’t already done it—or at least not lately—the more you have a shot at doing something that will be remembered positively for a long time.

The reality, though, is that we’re mostly taught to try to fit in, not how to take a flyer on the top five trends of our era. There’s a safety in fitting in. It’s what Irish poet and priest John O’Donahue wrote: “One of the sad things today is that so many people are frightened by the wonder of their own presence. They are dying to tie themselves into a system, a role, or to an image, or to a predetermined identity that other people have actually settled on for them. This identity may be totally at variance with the wild energies that are rising inside in their souls. Many of us get very afraid and we eventually compromise. We settle for something that is safe, rather than engaging the danger and the wildness that is in our own hearts.”

On the other hand, the more we focus on what we feel strongly about, something we really believe in, something we ourselves came up with or something we created out of others’ pieces, the more interesting it’s likely to be. Now, obviously, if we’re making something no one wants at all, or something no one’s willing to buy, then that isn’t going to work if we’re trying to make it in a business.

But I know from all the work on the Beliefs book that how much we believe in what we’re doing makes an enormous difference. When we’re doing something we really believe in, and what we do is done well, the odds go up a lot that we can make it work. It’s like Thelonius Monk said: “Play your own way. Don’t play what the public wants—you play what you want and let the public pick up on what you are doing—even if it does take them fifteen, twenty years.” Now, of course, businesses can’t generally wait fifteen years. But still, the point is the same. Doing something that you believe in, making a product or service that people don’t even know that they want until you make it…those are the people/businesses who become market leaders. Make something so interesting and special, unique but still accessible in its own special way, that people will go a long way to get.

Zingerman’s Art for Sale