Love, Leadership, Language, and the Life of Gustav Landauer

Putting the 100-year-old lessons of an “anarchist mystic” to work in the modern world

I’ve gotten a lot of wonderful notes about last week’s piece on love and work. Thank you. It’s both comforting and rewarding to know that the thoughts resonate. The encouraging words also got me wondering. The idea of love and work is wonderful, but… how can a leader effectively make love work, at work? How can the owner of a company shift the way its people see things to prove that love at work is possible? When so much of the news is dominated by anything but, how can we still structure our organizations to stay focused on putting love into the way we lead every day?

Fifty years or so ago, James Baldwin said, “The world changes according to the way people see it, and if you can alter, even by a millimeter, the way people look at reality, then you can change the world.” Earlier this week, Seth Godin wrote,

…learning requires us to break old habits and walk away from old ruts. It rewires our instincts and helps us see the world in a new way–not just see it, but act differently in it. It’s incredibly difficult to lever yourself out of a long-term rut. A community and a curriculum can make a huge difference.

Putting all these things together, to get love into work in meaningfully real, day-to-day ways, we need to shift some beliefs. We need to create mental frameworks from which love can emanate. One way, I’ve realized, is through language.

A long time ZingTrain client, J.D. Loeks from Celebration Cinemas, once suggested to me that here at Zingerman’s we speak our own language. He said we should call it Zinglish. Although I laughed at the time, later I realized that there was something to what J.D. had suggested. Earlier in the 20th century, linguist Edward Sapir said we think differently in different languages. Which would mean that folks at Zingerman’s think differently in Zinglish than most of the work world would in standard business speak. Most of the work world is not speaking Zinglish. And love is simply not in the language that focuses on things like “cost control,” share value, stock prices, and leveraged buyouts.

I’m currently reading Manchán Magan’s very marvelous book about Irish language, culture, and life called Thirty-Two Words for Field. About half way through the book Manchán says, “I certainly feel like a different person when I’m speaking Irish.” It makes total sense to me. I feel like a different—better—version of myself when I’m speaking (and thinking) in Zinglish. It is, I realize after writing that piece last week, a language that can move fluidly and fluently through and around the subjects of both love and work. Reflecting on last week’s piece and Manchán’s beautiful book, I would say now that we likely have at least thirty-two words for love in Zinglish. Things like Servant Leadership, Energy Management, Consensus, Stewardship, great service, appreciations, extra miles, caring conversations, visioning, Bottom-Line Change, etc. all make it easy to insert love into our day-to-day thoughts and actions.

So how can we help to make the language of love and work workable in organizations of all sorts? There are many places to look for answers, but my mind quickly went to the work of Gustav Landauer. “Love,” Landauer said over a century ago, “sets the world alight and sends sparks through our being. It is the deepest and most powerful way to understand the most precious that we have.” Back in 1919, Landauer was violently killed because of what he believed. For many reasons, I feel a responsibility to keep his beliefs and his spirit alive.

Knowing me as you do, you probably won’t be surprised to learn that Landauer was an anarchist. He was also, in whatever order one chooses to put them, German, Jewish, a pacifist, a poet, a teacher, a writer, and an avid swimmer. In person, Landauer was hard to miss—very tall (6’5”), he had long black hair that hung to his shoulders and he walked with long, loping steps. His mystique was enhanced because he frequently wore a long cape and a “unfashionable old hat.” Landauer was born in 1870 on April 7, in the middle of Passover, in Karlsruhe, into a family of middle class merchants. The pressure to conform, and his resistance to it, started early. His parents dreamed of him becoming a dentist; he wanted to pursue the arts. At university, Landauer studied German philosophy, history, and culture—in particular Spinoza, Schopenhauer, Rousseau, Tolstoy, Wagner, and Nietzsche. By the time he was in his early 20s he identified more and more fully with anarchism. In his early 30s, Landauer met German-Jewish philosopher Martin Buber and the two developed what became a lifelong friendship. He had a close relationship with his wife Hedwig, the daughter of a cantor from a small German town, and a poet in her own right. (She died the year before Landauer was killed, in 1918, of the Spanish flu.) Landauer did extensive translation of the works of Shakespeare and Oscar Wilde into German, and he went on to write some amazing essays and books. If you want an anchor closer to home, his grandson was the American film director Mike Nichols.

Eugene Lunn, who wrote a biography of Landauer, said he was a “gentle, thoughtful, humane man who was not given either to violent behavior or to doctrinaire fanaticism… without pontificating or talking down to anyone… Landauer was always a teacher.” Landauer, Lunn said, was committed to “moral honesty and social justice” with the “dedication of Isaiah to universal peace” and “the insistence of Ezekiel that all renewal requires an inner spiritual transformation of the individual.” Rudolph Rocker (whose book Nationalism and Culture is highly recommended) wrote that Landauer was “a spiritual giant… One felt when he spoke that every word came from soul, more the camp of absolute integrity.” In his day, Landauer was often compared for both his physical appearance and his temperament, to Old Testament prophets or to an “anarchist Jesus,” and was often referred to as “the anarchist mystic.” In a more modern context, I’m imagining Landauer as a bit of a cross between Wendell Berry’s focus on self-sustaining small communities, Gary Snyder’s “Buddhist Anarchism” and Ram Dass’ spirituality.

Landauer’s pacifism was not always popular, but he was very firm about it; his work was rooted, very much, in love. In a lesson that seems particularly on point for our own era’s power struggles, he said, “There can only be a more human future if there is a more humane present.” In complete contrast to the way he lived and what he believed, Landauer was kicked to death by German soldiers in Munich on May 2 of 1919 as part of the violence that occurred after the short-lived, duly-elected, revolutionary government of Kurt Eisner was overthrown by right wing troops. Landauer had at the time been serving in Eisner’s cabinet, where he held the title of “Commissioner of Enlightenment and Public Instruction.” I realize that Landauer still serves those roles for me today. His work has certainly enlightened me, and his writing has served as the sort of curriculum that Seth Godin is rightly suggesting we need. bell hooks wrote, “Life-transforming ideas have always come to me through books.” Reading Gabriel Kuhn’s translation of Landauer’s writing ten years ago transformed my life. Landauer showed me how love, spirit, positive energy, and hard work could be combined with individual dignity to yield collective—and in our case, business—community health.

Gustav Landauer’s writing provided me with much of the thinking that went into Secret #29 in Part 2 of the Zingerman’s Guide to Good Leading. It was both inspiring and insightful, and unlike anyone else I had read:

Rather than tearing down the state, Landauer looked for ways to build up positive community and support the individuals within it… to create caring free, communities in its place… His view is all about local, the positive, and the possible. This theme of Landauer’s runs through most everything I’ve written on organizations. Stop worrying so much about what others are doing wrong and take the initiative: dream big, do good things, and start going for greatness right here!

Part of what continues to inspire me about Landauer’s work is his insightful argument to start where we are—to work with care and love to create small communities, right now, that would make real the kind of radical caring, inclusive, loving work and relationships we aim for. For Landauer, that’s what anarchism was all about. (Yes, there were anarchists about who were engaged, famously, in acts of assassination and attempts to tear down governments. This is not, as I’m sure you know, my interest. At all. It wasn’t Landauer’s either. He wasn’t really known for his humor, but he did flash a bit of wit on occasion. “Those anarchists,” he wrote, “are not anarchic enough for me.”) Landauer also, appropriately and importantly, understood that the work to make all this happen had to begin inside ourselves. Landauer helped me realize that I had to do my own work if I wanted to make anything else better. If we were able to make those sorts of personal changes, Landauer believed—and I agree—we could create new, more loving, more meaningful, lives:

This world [we seek] can only be constructed from within… freedom can only come to life in ourselves and must be nurtured in ourselves before it can appear as an external actuality… what we are waiting for can only come from ourselves, from our own being… Whoever brings the lost world in himself to life—to individual life—and whoever feels like a true part of the world and not a stranger: he will be the one who arrives not knowing where from and who leaves not knowing where to. To him the world will be what he is to himself. Men such as this will live with each other in solidarity—as men who belong together. This will be anarchy.

Eugene Lunn suggests that even though Landauer looked like a bit of a prophet to those who knew him, he wasn’t one; that although he was murdered for his beliefs, Lunn says those beliefs died with him. I believe Lunn might have seemed correct at the time he wrote his book, back in 1973, half a century after Landauer’s death. But another 50 years down the road, here in 2021, I take a different view. In his book Crossing the Unknown Sea, author David Whyte wrote that,

A good artist, it is often said, is fifty to a hundred years ahead of their time, they describe what lies over the horizon in our future world… The artist, of whatever epoch, must also depict this new world before all the evidence is in. They must rely on the embracing abilities of their imagination to intuit and describe what is yet a germinating seed in their present time, something that will only flower after they have written the line or painted the canvas.

Landauer, I suggest, is the sort of spiritual and intellectual artist that David Whyte was writing about. And, as I wrote in Part 2, “Maybe that moment of applying Landauer’s insights ‘practically’ has actually arrived here in Ann Arbor.”

In Secret #29, I wrote about Twelve Tenets of my approach to what I called at the time, Anarcho-Capitalism which, if applied in an organization of any sort, could make for what I came to call “good work.” (There are, I learned later, others who use the term very differently than I do. I’m with Landauer—those “anarchists are not anarchic enough for me.”) The Twelve Tenets are something of a translation of Landauer’s century old writings into modern day Zinglish. They can, I believe, set the stage and make the space for us to make a loving workplace. They give us a set of beliefs, a learning regimen, and language to make love part of our daily work in a workable, business-focused way. And, best of all, they actually work.

Maggie Bayless and I taught a ZingTrain Master Class this past fall. (We’re working now on the next “semester,” to start in March, on Managing Ourselves if you’re interested.) One of the five weekly sessions focused on the Twelve Tenets. Much to my happy surprise, as I read back through them, I realized that we really have built these principles into the way we work here at Zingerman’s. No, we don’t get them right all the time. Still, they are now commonly held beliefs and everyday phrases that are used regularly when folks around here speak Zinglish. They’re woven into our 2032 vision and they’re in our new Statement of Beliefs. In fact, they’re so well established I don’t think too many “Zingernauts” (a bit of Zinglish for you) would even question them any longer. People who work here might, though, as well they should (and in line with what Landauer believed), point out where we can and should do them better. As Landauer said: “Anarchy is not a matter of the future; it is a matter of the present. It is not a matter of making demands; it is a matter of how one lives.”

This work—my interest in anarchist application to modern business; the Twelve Tenets I talk about in Secret #29, etc.—are not, in the spirit of Gustav Landauer, about preaching. Really, it’s all about practice. It’s about making love a part of work every day. It’s the belief that, imperfectly, we get to work now to make more lovingly effective communities. As Landauer wrote:

The following has always been true, is true now and will always be true: people live together in communities; people exchange goods and services over long distances; people are differentiated by language, custom, desire, and need; people believe that everyone looks out for his individual interest; however, some people stand up, make a change, and point the direction for the spirit and the courage of others. This is the reality that will always remain.

Throughout his life, Gustav Landauer spoke truth to love in ways that we can all put to work today, a century after he was so sadly and violently killed for what he believed. As I said in Secret #29, Landauer,

argued that, because revolution was all about tearing down and destruction, that it was actually regeneration—not revolution—that anarchism was all about. I would say the same here: Regeneration of spirit is, for us at Zingerman’s, the first order, helping each of us—those who work here and those we wait on—to feel better about ourselves, and freely choosing to bring our best out into the big wide world in the interest of supporting the greater good.

Spirit, for Landauer, meant love. And community. Two causes that are close to our collective hearts here at Zingerman’s. Another of Landauer’s biographers, Ruth Link-Salinger Hyman, said that “His fight was for an unending quest for love, cooperation, and justice.” There’s more to life and love and work than simply putting these Twelve Tenets to work. And it’s not an overnight project—we’ve been working on getting them into our culture and our language for years and we still fall short. I do believe though that they are a meaningful, down to earth, real life way to bring Gustav Landauer’s lessons about love, community, equity and positive energy into practice. I believe they can be put to work in a business, a not for profit, or in a classroom. And I believe, as per Landauer’s suggestion, that we can get going on this work right now to give us the kind of language we need to make love at work a daily practice and a practical reality. In his prophetic way Landauer foretold that future:

A time will follow in which humans, devoted to both themselves and to their surroundings, will once again climb mountains together to celebrate the renewal of life with fire and light. Inside of us, this time has already arrived. All we need to do now is to keep that spirit alive and spread it.

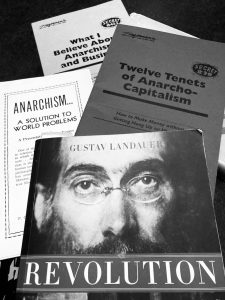

To learn more about the Twelve Tenets and putting Gustav Landauer’s worldview to work, see Secret #29. For more extensive reading on how anarchism can change our language of business, we put together a four-pack of anarchist pamphlets: Secret #29—Twelve Tenets of Anarcho-Capitalism, Secret #43.5—What I Believe about Business and Anarchism; Secret #32—It’s All About Free Choice, and “Going into Business with Emma Goldman.”

Zingerman’s Art for Sale