Going into Business with Emma Goldman

How an anarchist who died forty-two years before we opened the Deli has had a surprising impact on the way Zingerman’s works

“. . . geniuses precede events. Their work often remains ineffective for an extended period, appearing to be dead. It remains alive, however, waiting for others to apply it practically…” —Gustav Landauer

A few months ago, Food and Wine magazine’s Tracie McMillan put out a piece called “19 Great Restaurants to Work For.” As you will have guessed by my citing the article, we were on the list. There are dozens of factors that may have gone into making our organizational ecosystem one that won Tracie’s kind words. Many, I’d guess, we could have in common with the other 18 places on the list: good intentions, hard work, a spirit of generosity, a positive belief in people, and a desire to help folks overcome the many social barriers that get in their way as they attempt to live healthy and rewarding lives.

One thing that’s not in common for a restaurant, and one I doubt we have in common with the other restaurants on the list, is that we’re inspired by Emma Goldman, a woman that was once known as a “dangerous anarchist.” Although she passed away long before we did our first dollar’s worth of business at the Deli, Emma’s words have had a big impact on the way I work and the way I view the world. And through all of that, on Zingerman’s as an organization.

June 27, 2019, will be the 150th anniversary of Emma’s birthday. Emma was born in 1869, in Kovno, Lithuania. In 1885 she immigrated to the U.S. fleeing her oppressive, male-dominated, Jewish home life. Four months after her arrival in New York, the Haymarket bombing took place in Chicago. Eight anarchists were convicted for the bombing—probably inappropriately—and seven of the eight were sentenced to death.

Emma was among many Americans of that era who was pushed into more radical thinking because of the seeming injustice of the anarchists’ executions. Her interest in anarchism grew quickly and before long she was speaking regularly—about anarchism, feminism (though not women’s suffrage—she didn’t believe in voting or representative democracy), birth control, education, and drama. By the end of the 19th century, she was probably the single most controversial person in the country. The details of her life are well documented so I won’t go on here—you can read her whole bio online, or in the fine books of Candace Falk, Kathy Ferguson, Alix Kates Shulman, Vivian Gornick, and others.

I have what I think of as a “working relationship” with the woman whom the young J. Edgar Hoover once called “the most dangerous woman in America.” When Hoover made that statement, Emma was all of 24 years old.

Connection; Emma and edits

When the books in the Zingerman’s Guide to Good Leading series have gone through various stages of editing, I’ve had the comment from experts that when I cite authors I don’t know personally, the correct editorial form would be to introduce them to the book first by their full name, and then later refer to them only by their last name. For example, “Irish philosopher John O’Donohue” would be used for the first reference, and then after that, merely “O’Donohue.” The only exception, I’ve been told, should be for folks with whom you’re actually friends, or have a personal relationship. While I’d adopted proper citation rules in the books, there were some spots, the editor pointed out, where I’d slipped. In particular, with Emma Goldman. I kept calling her “Emma” which might be perceived as disrespectful, or maybe even demeaning because she was a woman. It was suggested to me then that, to be proper, I ought to take out my many references to “Emma” and replace them with “Goldman.”

While I know the advice is technically accurate, it just didn’t sit right with me. This wasn’t at all disrespect; it was about dedication. “I know it probably sounds crazy,” was my ultimate response, “but I actually feel like I have a long and real relationship with her. I’ve spent so much time reading her work and reading about her, that I feel like I know her at a much deeper level than I know a lot of the—living—people I see all the time!” “Goldman” sounds way too formal and far more distant than feels right for me. Her friends often called her E.G. — I think of her in my head as “Emma.”

Vivian Gornick, one of Emma’s many skilled biographers, said, “Every writer writes about the people they know. It’s all you really have. The life you’ve lived, the experiences you’ve had, the people you know, they’re your raw material.” Emma Goldman, and her work, are part of mine.

Somewhere, maybe in my sophomore year at U of M, I started reading the written work of historically interesting anarchists — Emma was one of the first. Bakunin, Kropotkin, and others came along as well. At some point, I began going up to the Labadie Collection on the 7th floor of the Graduate Library to look at old books and pamphlets.

Best I can recall, my real introduction to anarchism in print came from Paul Avrich’s book, The Anarchists. It includes, of course, a chapter on Emma. Her writing resonated deeply with me—she was speaking “truths” I wasn’t hearing from others. She had a way of saying things that struck an intellectual, and emotionally engaging, chord with me. Getting to know her through her writing was, in practice, like meeting that mentor I’d never had. Her work helped me feel . . . heard. I can most certainly imagine having a lot of long and interesting conversations with her over good meals and good coffee.

When she wrote, “What is more astonishing is the fact that parents . . . will put the long lean finger of authority upon the tender throat and not allow vent to the silvery song of the individual growth, of the beauty of character, of the strength of love and human relation, which alone make life worth living. . . . That compulsion is bound to awaken resistance, every parent and teacher ought to know,” it felt like exactly what I (and I’m sure a few million other) teenagers had experienced. Having grown up in a rather religious setting, I’d been feeling that way in my family, and in school, since the time I was . . . maybe ten.

To get that sort of resonance from a woman who based on her timeline might have eaten potato latkes with my great grandmother, seemed a wholly unexpected, but wonderfully welcome, incongruity! Stuff that she wrote long before I was born rang so true to me: “What is generally regarded as success-—acquisition of wealth, the capture of power or social prestige–I consider the most dismal failures.” Her statement was something like seventy-years old, but it summed up a lot of what I was thinking in 1977.

Integration; Zingermans and Anarchy

Though Emma’s work deeply resonated with me during my studies, when I graduated from U of M with a history degree, my immediate interest was mostly in finding work that would allow me to a) not go home to Chicago, and b) pay my bills. The whole story is in the Zingerman’s Guide to Good Leading books, so I won’t bore you here. Flash forward to 1982, the year we opened the Deli. Emma Goldman was mostly out of sight and out of mind that day and really for most of our first 26 years in business. Over all those years, we got a fair few awards and a host of local and national recognitions, but nothing got me thinking about her writing.

But then . . . one day in 2008, while I was working on Zingerman’s Guide to Good Leading, Part 1, I was asked to speak at the Jewish Studies department at U-M. The talk was scheduled for the following fall and I was given the title “Rye Bread and Anarchism.” The former, a reference by department chair Deborah Dash Moore to my modern-day work, and the latter to my earlier academic interest. Busy as usual, I didn’t think much about the topic at the time I received the speaking invitation. But over the course of the summer preceding the talk, I realized that although I’d recently written an in-depth article on the history of Jewish rye bread, I hadn’t looked at anything to do with Emma Goldman in ages. Not wanting to embarrass myself in front of the well-versed professors who I imagined would be in attendance, I dug out a stack of my old anarchist books and started to reread them. What I found blew me away.

The classic headline of anarchist beliefs—getting rid of government—was strongly present in what I was reading, but that’s not what caught my attention. Government isn’t something I have strong feelings about one way or another. Instead, I stumbled onto a treasure trove of creative concepts that sounded surprisingly similar to the progressive business literature I’d been reading so much of over our then-26 years or so at Zingerman’s.

So many things that were integral to old anarchist thinking seemed to already be embedded in the way we were working at Zingerman’s. The idea that the point of an organization is to enhance the lives of the people who are a part of it; that involving more people in managing the work they’re doing makes good sense; that there’s wisdom in everyone who works in an organization; that when men and women don’t believe in what they’re doing, they don’t do good work; that when people are treated like interchangeable machine parts, they aren’t inspired to reach for greatness; that anyone can learn to lead; that the point of the organization is to serve those who are part of it.

This quote, from Emma’s book, Anarchism and Other Essays—one that I’d long since forgotten about—is what sealed the deal for me. “[Our] goal is the freest possible expression of all the latent powers of the individual . . . [which is] only possible in a state of society where man is free to choose the mode of work, the conditions of work, and the freedom to work. One to whom the making of a table, the building of a house, or the tilling of the soil, is what the painting is to the artist and the discovery to the scientist—the result of inspiration, of intense longing, and deep interest in work as a creative force.”

While she was writing about anarchism, I immediately related it to the sort of environment we’d been seeking to create at Zingerman’s since we opened in 1982. It’s at this point I would say my “working relationship” with Emma really got going. I began taking the concepts and ideas she’d written about and trying to figure out how to consciously implement them in our organization, even more than we’d already unconsciously done.

Applying Emma’s Anarchism to Business

What is it about Emma’s words that made such a big impact? Here are a few of the things that have helped to make my own business philosophy—and in the process, our organization—what it is.

“Anarchism aims to strip labor of its deadening, dulling aspect, of its gloom and compulsion. It aims to make work an instrument of joy, of strength, of color, of real harmony, so that the poorest sort of a man should find in work both recreation and hope.”

In a joint talk on “Individuality, Autonomy and Organization” at the International Anarchist Congress in Amsterdam in 1907 Emma and Max Baginski said:

“There exists an erroneous conviction that organization does not encourage individual freedom and that, on the contrary, it causes a decay of individual personality. The reality is, however, that the true function of organization lies in personal development and growth …”

This is, of course, exactly what we hope to do at Zingerman’s. We’ve long believed in creating a positive workplace one in which people feel honored and respected. As I write today, that commitment is being drafted into our still-in-the-works organizational vision for 2032.

“An organization . . . must be made up of self-conscious and intelligent persons. In fact, the sum of the possibilities and activities of an organization is represented by the expression of the single energies [of the group].”

To me, this was akin to Jim Collins’ now famous statement about “getting the right people on the bus” in your business. You can’t have a great organization without great people. And—of equal import—the people who do the best work here are the most “self-conscious,” or I would say, “self-reflective.”

“It follows logically that the greater the number of strong, self-conscious individuals in an organization, the lesser the danger of stagnation and the more intense its vital element . . .”

We actively teach everyone how to think like a leader from the time they start—the more everyone is pushing for greatness, the less likely we are to slip into getting stuck in the status quo and the stagnation Emma and Max were talking about.

“In short, anarchism struggles for a form of social organization that will ensure well-being for all.”

This has been a part of our philosophy at Zingerman’s since we opened in 1982—creating a business committed to helping everyone it touches!

Emma and Emotional Intelligence

Part of what resonates so strongly for me with Emma’s work is that she emphasized the internal and emotional well-being as much she did external and economic issues:

“Anarchism is the only philosophy which brings to man the consciousness of himself.”

“No formulaic change in social conditions [is] a guarantee against subjugation to one’s inner tyrants.”

“The problem that confronts us today, and which the nearest future is to solve, is how to be oneself, and yet in oneness with others, to feel deeply with all human beings and still retain one’s own characteristic qualities.”

These are just a few of her many references to the import of self-awareness. She understood what most people still don’t—that freedom is an inside job, not something to be “won” from a “ruling power.”

Anarchism “is the spirit of youth against outworn traditions.”

A critical voice in support of innovation and creative energy. And also a clear, and I believe accurate, statement that getting stuck in the status quo is not tied to age. We’re all about traditional food, but I don’t ever want Zingerman’s to become an “outworn tradition!”

“Every sensitive being abhors the idea of being treated as a mere machine or as a mere parrot of conventionality and respectability, the human being craves recognition of his kind.”

This is embedded in all of our work. To treat everyone who works here—and I would suggest everyone, anywhere—as a unique, creative individual, never to assign them an identity based on job title, age, gender, race, etc. I was sharing this essay with Amanda Peters who works in the kitchen as Miss Kim, who commented. “It’s true! This is the first job I’ve had where I wasn’t treated like a machine part!”

“When we can’t dream any longer, we die.”

The death that most people in most businesses “die” is a spiritual one. I call it the “working dead.” People show up, but they have no hope for a better future, no belief that they can make a difference. To avoid that . . . we do a number of things, probably most importantly, we teach our visioning process—a technique for effectively talking about inspiring but still strategically sound futures—to everyone who works here!

Emma and me

Bringing past and present, fantasy and reality, books and business together . . . a whole bunch of questions come quickly to mind. Would Emma and I have actually gotten along? Would we have been able to make it as business partners? I mean, clearly we have all these beliefs and values in common. She was a relentless worker who never stopped learning and pushing towards her vision. She wasn’t afraid of taking on challenging situations and she was certainly more than willing to speak her mind in awkward situations. She was definitely a kick-ass communicator. She liked a good party and loved to orchestrate social scenes, an important skill in the restaurant business. She liked to cook, and clearly had an affinity and a palate for great food. And she did that have experience in the ice cream shop . . . hmmmmmm . . . .

Transporting her mentally into the modern world, I can imagine her taking on “Big Ag” and industrial growing methods, advocating with great passion for small farmers and small business; being an outspoken advocate for local agriculture. Really, it’s not all that hard for me to imagine her sitting around the table at our Partner’s Group meeting, alienating some of the others at the table, pushing us to do better, arguing her case, bringing energy and insight to the organization.

In the words of Emma’s biographer Vivian Gornick, “anarchism [as Emma knew it] prepared one for nothing on the ground.” In other words, “nice idea, but completely impractical.”

But, sitting here in 2019, in the months before what would have been Emma’s 150th birthday, working in what the world would probably call a “successful” and certainly a “progressive” business, I would say the opposite. I think the philosophies Emma was eloquently and passionately putting out in the world were all about working “on the ground,” about the practical approaches to human interaction—on which all business relies—to work in inspiring and effective ways.

What I can say is that I’m one of the only modern day business owners who regularly draws on Emma Goldman’s work for inspiration and organizational insight. I’m pretty certain I’m the only person who regularly quotes her on stage when speaking at business conferences, or who references her regularly in books on leadership and business. And I feel fairly confident that I’m on the only U of M commencement speaker to quote her (and anarchist Ashanti Alston) from the stage at the “Big House” in front of 50,000 people. (For the transcript of the speech see Part 4 of the Guide to Good Leading.) And I can say with great certainty—as you’ve seen above—is that we have absolutely taken Emma’s ideas into business in very real, and very meaningful ways.

Living, for a few minutes at least, in the imaginary, I’d like to think that had she been a part of the Zingerman’s Community of Businesses, maybe, just maybe, should would have shared her enthusiasm as she did when she experienced the (short-lived) success of the anarchists during the Spanish Civil War. “I am walking on air,” she wrote. “I feel so inspired an so aroused that I am fortunate enough to be here and to be able to render service to our brave and beautiful comrades. . . One completely forgets oneself and everything of a personal character amidst the life of [this] collective spirit.” It’s certainly how I feel.

Imagination aside, we’ll never really know what would have, or could have happened were Emma to appear magically in our own era to be a partner at Zingerman’s. But I’m comforted by this closing thought, a motto I admire and can relate to, from Emma that I found in Paul Avrich’s Anarchist Voices: “When things are bad,” she said, “scrub floors.” That’s a business philosophy we’ve lived by at Zingerman’s since the day we opened!

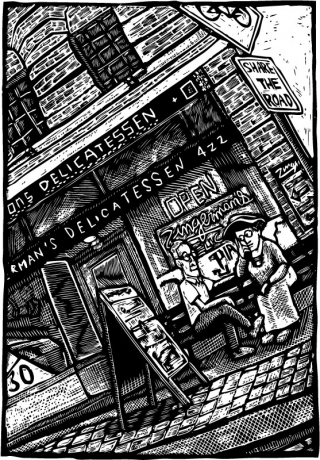

Zingerman’s Art for Sale