Going into Business with Emma Goldman

How an anarchist who died forty-two years before we opened the Deli has had a surprising impact on the way Zingerman’s works “. . . geniuses precede events. Their work often remains ineffective for an extended period, appearing to be dead. It remains alive, however, waiting for others to apply it practically…” —Gustav Landauer A […]

Read more »

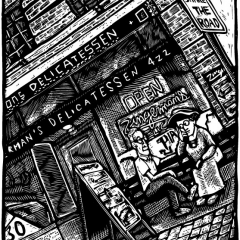

Zingerman’s Art for Sale