The Power of Positive Beliefs

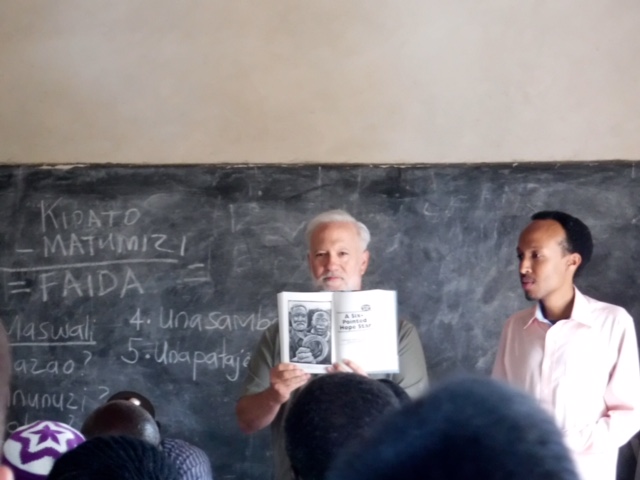

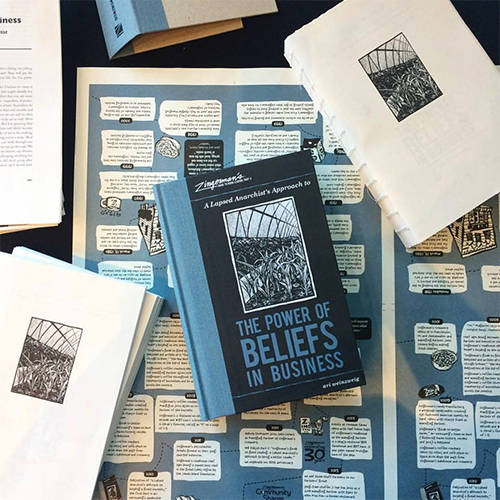

Marveling at the difference a small shift in beliefs can make in every aspect of our lives As I write, we’re in the process of putting the final touches on the first-ever “Zingerman’s Statement of Beliefs.” We’re working on getting them printed so we can give copies to our staff, and so those of you […]

Read more »

Zingerman’s Art for Sale